The Green List: A Framework for Measuring Species Recovery and Conservation Impact

The Green List: A Framework for Measuring Species Recovery and Conservation Impact

By Dr Samantha Nicholson – senior carnivore scientist, Endangered Wildlife Trust.

Conservation efforts are essential for conserving species, and it is important to focus on how species can recover and thrive over time with such efforts. The IUCN Green Status of Species is a new tool that works alongside the Red List to track species’ recovery and measure the impact of conservation actions. In this article, we’ll explore how the Green Status is helping shape a more optimistic approach to conservation, starting with the lion, which was recently assessed for the first time.

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species is globally recognised as the standard for assessing the extinction risk of species. However, an optimistic approach to species conservation is also essential, providing a roadmap for recovery and measuring the impact that conservation efforts have had on that species’ status. To complement the Red List, the IUCN Green Status of Species was developed to assess species recovery and the impact of conservation efforts.

The Green Status works alongside the Red List by evaluating how species populations are recovering and tracking the effectiveness of conservation actions. These assessments are crucial, offering a clear measure of recovery and the success of conservation initiatives. While the Red List highlights species that are threatened, the Green Status provides an additional perspective by measuring how much a species has and can recover. This helps identify successful conservation strategies and areas where further efforts are needed. By monitoring a species’ recovery, Green Status assessments allow conservationists to celebrate successes, maintain support for conservation projects, and adjust strategies for better outcomes. They also emphasise the importance of long-term conservation planning to ensure that species not only avoid extinction but also thrive and reach sustainable population levels. Furthermore, the Green Status contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of biodiversity conservation by emphasising both the prevention of decline and the restoration of species to healthy populations.

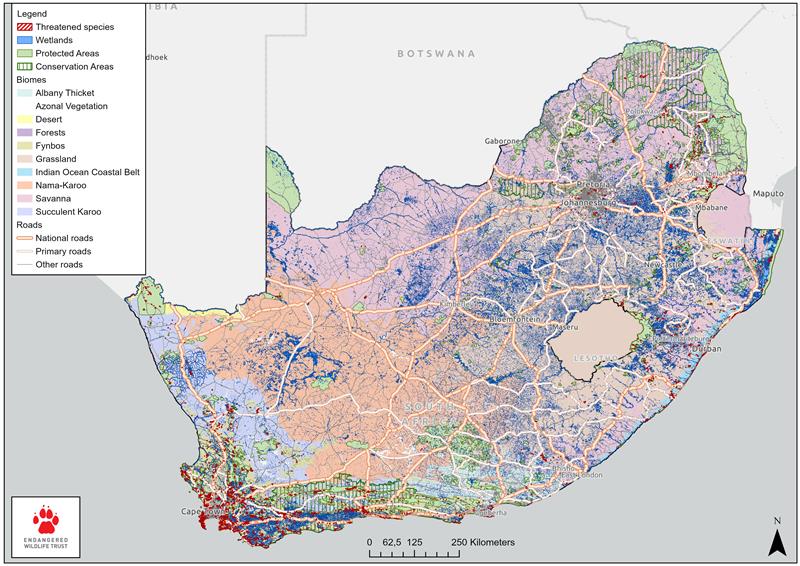

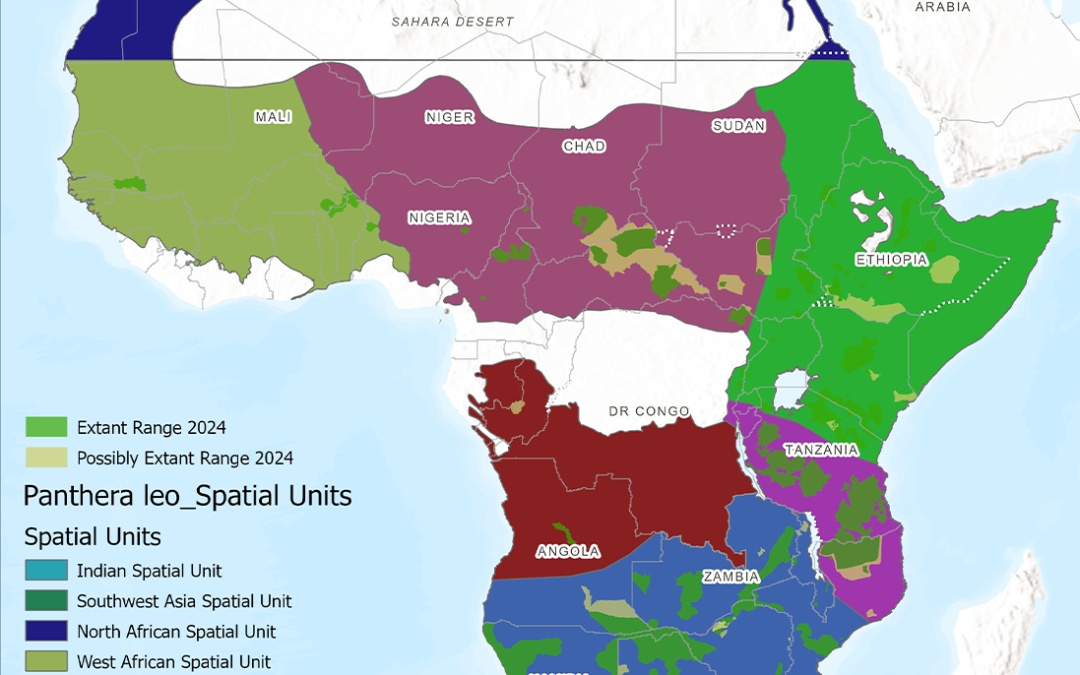

In 2024, the lion’s (Panthera leo) Green Status was assessed for the first time. The assessment revealed that the species requires intensified conservation efforts. The lion’s recovery score was 30%, classifying it as “largely depleted.” We broke the indigenous range of the species into ten spatial units – a spatial unity being a distinct geographic area or boundary (Figure 1). The species is most likely absent in two of its ten spatial units, likely viable in one, and present in the remaining seven. This reflects a significant decline from historical levels. While lions may still exist in some areas, their numbers are far lower than before, and they face substantial survival threats.

Figure 1. Map of the indigenous range of the Lion delineated into ten spatial units. Current range is based on the latest Red List Assessment (Nicholson et al. 2024): Extant range = Green; Possibly Extant Range = Light Yellow Green. Spatial units are as follows: Light Blue = Indian; Dark Green = Southwest Asia; Dark Blue = North African; Yellow-Green = West African; Pink = Central African; Bright Green = East African; Purple = Tanzanian Northern Mozambique; Red = Southern Central Africa; Blue = Southern Africa; Olive Brown = South African.

A key component of the Green List is determining a species’ “Conservation Legacy,” which compares its current Green Score to what it would be if no past conservation efforts had taken place. The lion, despite its depleted state, has a High Conservation Legacy, indicating that without past conservation actions—such as protected areas and legal protections—its population would have declined even further. The species’ conservation dependence is classified as “Medium,” meaning that its long-term survival and recovery rely moderately on continued conservation efforts. While lions may not face immediate extinction without these actions, they would experience significant population declines and escalating threats across their range. Without ongoing conservation measures like protected areas, legal protections, and active management, the lion is expected to be extirpated from three spatial units within the next decade. This highlights the urgent need for sustained conservation efforts to prevent further declines and ensure the species’ survival.

The Green Status evaluation shows that human activities are obstructing the lion’s ecological functionality across its range, with significant declines in many areas and extinction in North Africa and Southwest Asia. However, the assessment also emphasises that conservation efforts have helped prevent the species’ extinction in regions such as West and Southern Central Africa, South Africa, and India. To preserve the remaining populations, intensified conservation actions are critical, especially as human settlements continue to expand across the lion’s habitat.

The Green Status assessment of the lion highlights the critical need for continued and strengthened conservation efforts to safeguard this species. While the lion’s population has dramatically declined and has vanished from parts of its former range, conservation measures such as protected areas and legal safeguards have played a key role in preventing its extinction in certain regions. Despite these successes, the species’ medium conservation dependence suggests that sustained and enhanced actions are crucial for its long-term survival.

As human development increasingly impacts lion habitats, it is essential to not only protect existing conservation areas but also to actively manage and expand them. Additionally, increasing funding and support for Conservation organisations working in the field is vital to ensure that these efforts are effectively implemented and scaled. Conservation organisations provide expertise, conduct vital research, and mobilize local communities, all of which are crucial for species recovery. Without these resources, vital conservation work may struggle to achieve lasting results. The Green Status approach is a powerful tool for measuring progress and identifying areas where further action is needed. Ultimately, the lion’s future underscores the importance of long-term commitment, adequate funding, and global collaboration in protecting biodiversity for future generations.

Nicholson, S., Aebischer, T., Asfaw, T., Bauer, H., Becker, M., Bertola, L., Breitenmoser, U., Carlton, E., Fraticelli, C., Henschel, P., Hunter, L., Laguardia, A., Loveridge, A., Ndiaye, M., Roy, S., Sogbohossou, E., Scott, C., Strampelli, P. & Venkataraman, M. 2024. Panthera leo (Green Status assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2024: e.T15951A1595120251. Accessed on 31 March 2025.