Driving north from Cape Town towards Namibia you enter a landscape that looks dry, inhospitable and unforgiving—an area known as the Knersvlakte and Namaqualand, or the Drylands.

This is a sparsely populated region of South Africa, but a landscape that hides an extensive biodiversity and a high number of endemic species. It is a landscape where drought and low rainfall are part of the people’s lives; an area pock-marked by the destruction of natural habitats by mining along the coast and inland.

The far reaches of the Western Cape bordering on the Northern Cape, stretching from coastal towns such as Doringbaai to north of Brand-se-Baai inland to areas like Gamoep and Kliprand, you will find numerous mines. This includes the Steenkampskraal Monazite Mine, an important producer of rare earth minerals, and uranium, as well as South Africa’s Radioactive Waste Disposal Facility at Vaalputs. Many mines have closed over the years with little rehabilitation, leaving damaged habitats in the landscapes.

It is here that the Endangered Wildlife Trust’s Drylands Strategic Landscape is working closely with farmers, landowners and communities to identify critical biodiversity areas that need to be protected while addressing the existing scars in the landscape due to historical and current prospecting and mining activities. It is vital to ensure the long-term conservation of the Succulent Karoo, as any scarring or damage to the top layer of soil will result in a form of erosion. Through continued research and support, the EWT aims to provide landowners with scientifically-based evidence of the unique and endemic species found on their properties. As the drylands have very little documented information on the unique biota, it will ensure further robust specialist studies can be conducted if prospecting and/or mining applications are encountered. Continued work in the arid lands through rehabilitation will ensure more site specific information is available to implement arid land rehabilitation, and provide accurate rehabilitation costs to be considered. Because prospecting applications are increasing, it is important to ensure that landowners and land custodians understand the value of the biodiversity found on their properties, as this knowledge could inform the outcome of a prospecting or mining application.

Namaqualand and the Drylands, are landscapes of united communities encompassing people living in small towns, on farms, in shelters and isolated homesteads, all interdependent on each other for continued survival. The community is dedicated to conserving and maintaining the veld, while also restoring degraded lands because of the dependence on the veld for survival alongside their relationship with the endemic species found here. Landowners understand that decisions made today will have an impact for 50 to 100 years, and that they must farm smart to ensure a life for future generations.

Despite numerous challenges related to the approval of prospecting and mining rights on private properties, farmers in the drylands are adamant that they will not be forgotten or overlooked.

Local farmer Mari Rossouw believes their community is often overlooked because outsiders often question why anyone would want to live in this “unforgiving landscape”. Often applicants for mineral rights further underestimate the local knowledge and the power of the community.

Kliprand farmer Sarel Visser feels the area is being exploited because of its low population density, the assumption that there will be no fight to protect arid lands. He points out that mines in the landscape have a 10 to 15-year lifespan and are thus not viable. Farming, tourism and conservation are the future, he argues.

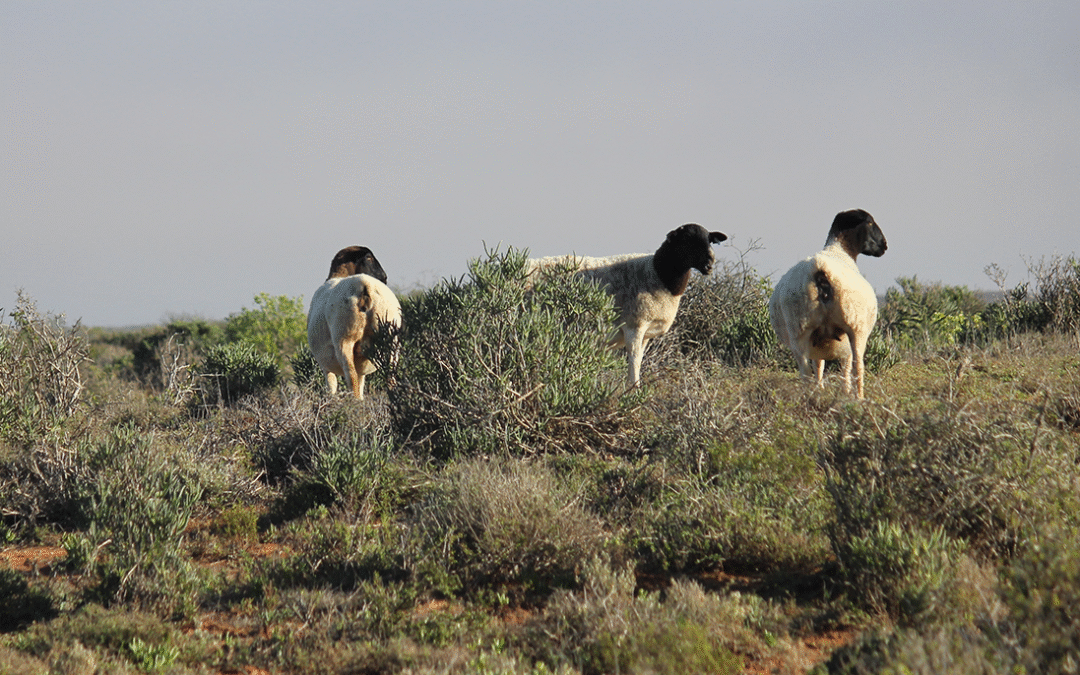

“They are destroying our entire ecosystem and destroying the lives of the people in a community that lives in constant uncertainty. We are already the last generation able to farm with sheep in this area,” he says.

What are the challenges?

Namaqualand and the Knersvlakte are drought-prone, with an annual rainfall of between 150mm and 300mm.

It is a landscape bent under the pressure of prospecting and the threat of further mining that will permanently scar the landscape. Communities living here are not willing to sit back and accept prospecting applications that are either factually incorrect or badly translated into the predominant language spoken in the region—Afrikaans. The community has had to upskill to ensure applications were commented on as part of the public participation process, and then how to appeal mining applications on their farms. Further challenges include prospecting applications being approved despite containing incorrect geographical and environmental information.

Among the community’s concerns is the fact that the Matzikama municipality’s 150km coastline, bar one kilometre, is being mined, or has mining rights allocated; a lack of rehabilitation and restoration of historical mining areas; a lack of adequate rehabilitation funds built into prospecting applications; the removal/destruction of topsoil; and not being able to sustain restoration. Another concern is the lack of financial means available to landowners to create and register a protected area on their properties.

Since 2019, there have been 54 prospecting applications on properties owned by 20 farmers in the Kliprand area alone. While all have been denied, and three are presently under appeal, three new applications were received in mid-June 2025.

Landowners become emotional when they speak about how the soil and the micro-organisms found in topsoil die when this is removed. In an area where plant growth is already vulnerable, the veld never fully recovers as the topsoil becomes sterile when removed.

Chair of the Knersvlakte Conservancy Kobus Visser says that if you drive over or step on a plant you can kill it. The damage caused to certain plant species is unique to this environment because of its complexity. Rehabilitation can take up to 100 years “or never”.

Seventh generation farmer Christiaan Pool says his farm, on which Vaalputs is situated, is a clear example of this. Areas damaged in 1974 have still not been restored to their former state.

Sarel says an area last ploughed by his father in 1967 has not fully recovered either, while Magarieta Coetzee says an area on their farm damaged by historical over-grazing more than 60 years ago has also not returned to its original state.

Drought and damaged soil, they say, also affect the feeding value of the Kraalbos (Galenia africana), which has a higher nutritional value for sheep than lucerne.

Farmers, landowners and community members gather together with the EWT to discuss solutions to the challenges facing the Drylands

Solving land degradation

Mari and a team of more than 60 local community members have been working closely with several mines and a State-Owned Enterprise in the last 24 years to rehabilitate degraded areas on the West Coast.

They have transplanted more than 4.5 million plants in degraded areas, in many instances augmenting the work being done by some of the mines. Rehabilitation costs are astronomical.

Once the sand has been stabilised, seeds of cultivars found in that particular area is transplanted, invasive alien species are controlled and rows of netting is installed for wind mitigation stabilisation.

Among these are succulents, a vegetation type largely threatened by illegal trade. Saving these species is proving to be more difficult than previously thought “because we struggle to get the soil to a point where these plants will be able to survive,” says Mari.

They plant cultivars with strong rooting systems such as the Pelargonium, Wag ‘n Bietjie, Buchu, Papierblom, Pendoring (Pin Thorn) and Kapokbos between the rains in the winter to ensure they grow. This, in turn, attracts birds and other small mammal species back to the area.

For Mari it is important that the aesthetic value of the environment “must remain for when we are not here anymore, in 30 years”.

Sarel believes that the longer-term employment and economic solution for this region is conservation, tourism and other land rehabilitation projects.

Johan Truter and Christiaan Pool add that conservation is the future, but that they don’t have sufficient funding to have their farms declared protected areas. This is despite their properties already meeting the criteria for Biodiversity Stewardship in terms of vegetation units and the region’s unique biodiversity.

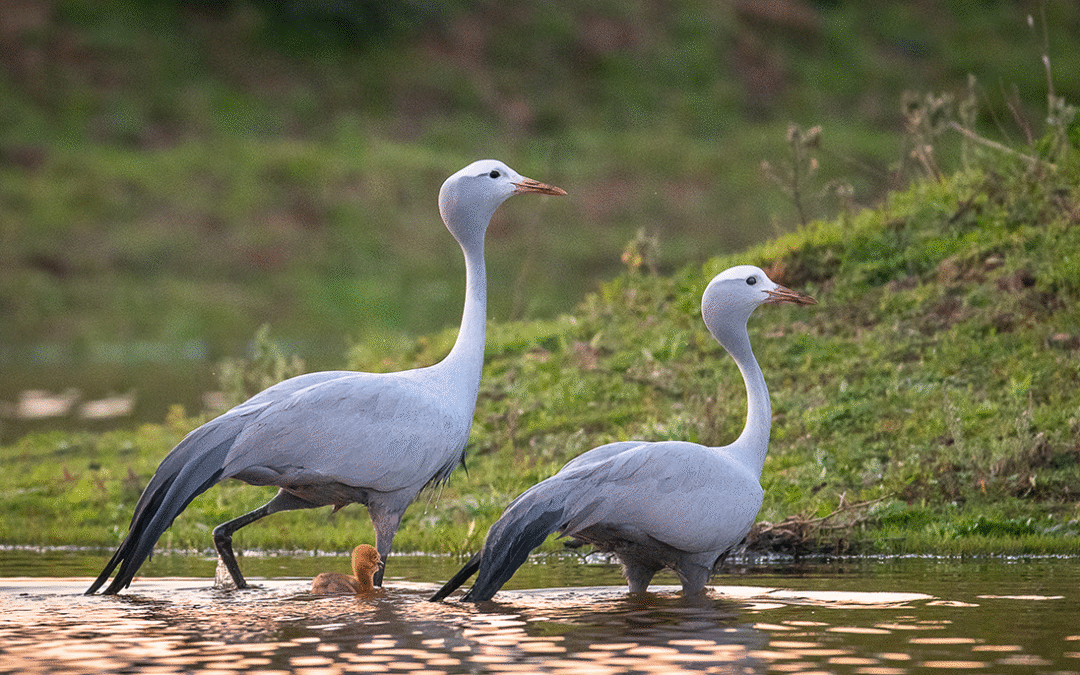

This community is calling for a moratorium on all prospecting in their landscape so that the EWT and other researchers can undertake a proper study of all the species found here. In the past two years the De Winton’s Golden Mole, for instance, was rediscovered after an absence of 87 years. The area is home to the Western (“Namaqualand”) tent tortoise (Psammobates tentorius trimeni), Speckled Dwarf Tortoise (Chersobius signatus)—two of the threatened reptile species in South Africa, the Endangered Black Harriers (Circus maurus), and a variety of Threatened and Endemic succulents and invertebrates.

It is also where the EWT is helping communities and landowners to explore alternative income streams to take the pressure off the natural resource base in terms of agricultural production. This includes the introduction of ecotourism activities that not only create jobs, but bring much-needed income to the region. In 2020 and 2024, we officially launched mountain biking, trail running and the Via Ferrata routes on Papkuilsfontein, near Nieuwoudtville. These trails help diversify farming income through adventure tourism and balances nature-based income generation and farming activities.

Kobus Visser says to succeed as conservancies or protected areas, the Namaqua and Knersvlakte communities need to know what is on their land, thus the importance of working with NGOs such as the EWT. It is through science and knowledge that success will be achieved, he says, pointing out that were it not for researchers such as Zanné Brink, or Renier Basson of the EWT they would not know that certain tortoise or insect species live on their farms.

He adds that the farmers have learned to live with global warming, adapting their farming practices to ensure the veld remains resilient to climate change. The Knersvlakte Conservancy, he says, is an area that showcases this—the will of the community to establish something to ensure like-minded conservation outcomes.

“We have all our plans in place and are busy with a proposal to open an office before the end of the year. Then will be able to concentrate on physical projects to increase our knowledge, like insect surveys with the EWT,” he says.

Zanné, the EWTs Drylands Strategic Landscape manager, says continued efforts are ensured through working with provincial authorities to align provincial and national biodiversity legislation and regulations that would further ensure the safeguarding and extension of protected areas and informing Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) practices.

“To establish a conservancy, other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs) or a protected area, it starts with the land and the will to ensure the long-term protection of the environment. Within Namaqualand and the Knersvlakte, the community is ready for this opportunity that cannot be lost,” she says.