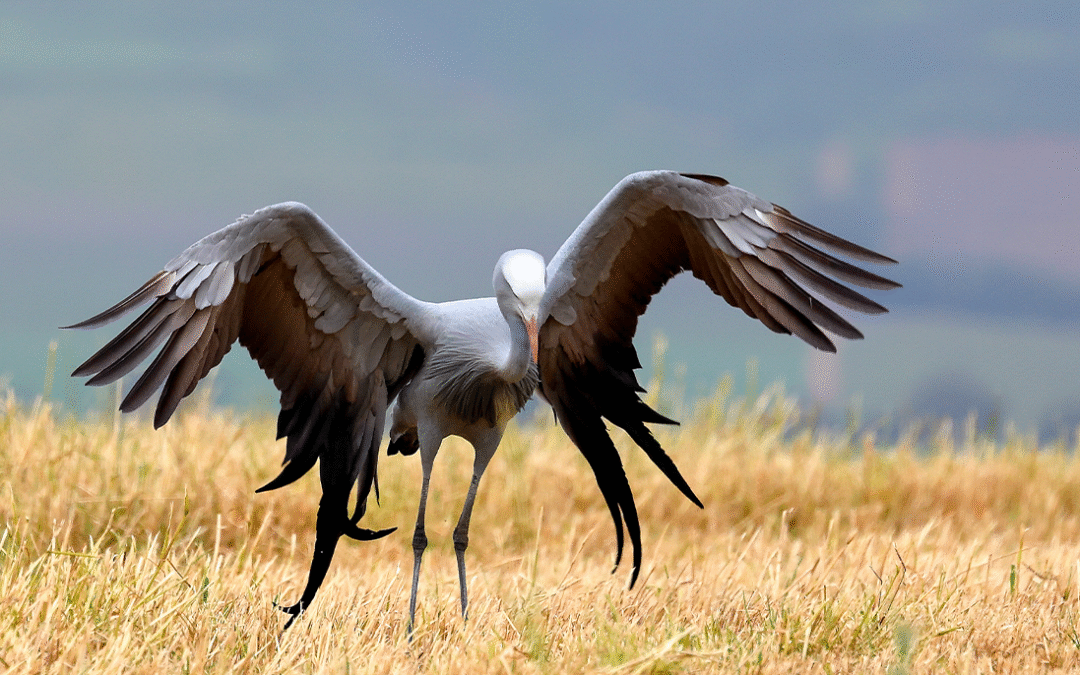

Blue Crane Conservation: Protecting South Africa’s National Bird

Blue Crane Conservation: Protecting South Africa’s National Bird

By Dr Christie Craig, Conservation Scientist

Image Credit: Pieter Botha

September is Heritage Month in South Africa, a time when we focus not only on our cultural, but also natural heritage, most notably our National Bird, the Blue Crane.

To ensure the continued survival of this species, and its growth in areas where it has shown decline in recent years, the Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT), through our partnership with the International Crane Foundation (ICF), has increased its efforts to conserve the Blue Crane, with a strong focus on the Western Cape and Karoo.

Decades of successful conservation interventions have yielded positive results in KwaZulu-Natal and the Northern Cape, and attention is now being directed to populations in the Western Cape, with the same positive outcomes being targeted.

Blue Cranes are endemic to South Africa, with a small population found in Namibia, making these the world’s most range-restricted crane. There are less than 30,000 of these birds left in the world.

As part of our Heritage Month celebrations, and to mark Heritage Day on 24 September, the EWT/International Crane Foundation partnership is expanding its existing activities to safeguard the future of Blue Crane populations in the Western Cape, by intensifying our focus on habitat restoration with communities and farmers, and addressing threats posed by energy infrastructure.

The Blue Crane (Anthropoides paradiseus) is an important element of South Africa’s natural heritage, serving as a flagship for conservation in agricultural landscapes, from the rolling grasslands of KwaZulu-Natal to the expansive plains of the Karoo, to the patchwork of crops and renosterveld in the Western Cape.

Since 1994, the EWT/International Crane Foundation partnership has been committed to Blue Crane conservation in South Africa, running projects in the grasslands, Karoo and Western Cape. Over the last 10 years, the majority of our applied crane conservation work has focused on the Drakensberg region, where Blue Cranes have historically faced steep declines. With consistent conservation action, including natural habitat protection, powerline impact mitigation and community projects, Blue Crane numbers are now slowly increasing, testimony to the success of our conservation activities.

Until 2010, Blue Crane numbers were increasing and healthy in the Karoo and Western Cape. However, a recent PhD study supported by the EWT/ICF Partnership reveals that numbers have subsequently been declining in these areas, especially in the Overberg ,where counts have dropped by 44% between 2011 and 2025. For more info on the reasons for this decline, see our June press release.

This has sparked the need for renewed conservation effort underpinned by a multi-stakeholder conservation plan, which was developed with the help of the Conservation Planning Specialist Group, gathering inputs from NGO, industry, landowners, communities and government.

The conservation plan comprises four parts:

1: Habitat protection.

The partnership will continue its commitment to Blue Crane conservation in the Drakensberg through ongoing habitat protection and will expand this work from the Western Cape into the Karoo.

2: Addressing energy infrastructure impacts.

Because Blue Cranes are particularly susceptible to colliding with energy infrastructure, the relationship with energy suppliers is being expanded to address this issue through powerline mitigation and improved infrastructure routing.

3: Crane Friendly Agriculture

Engagement with the agricultural industry is increasing to co-create solutions that allow Blue Cranes and other species using the agricultural matrix to thrive alongside agricultural production. Blue Cranes are especially dependent on agriculture in the Western Cape, but also use agricultural habitats in the Karoo and grasslands. Work in the agricultural sector will focus on addressing threats such as poisoning and breeding disturbance, as well as helping farmers address crop damage issues.

4: Research and Monitoring:

This is an essential underpinning of any good evidence-driven conservation project. Through monitoring Crane numbers and breeding success, we will be able to gauge our impact. Without research, we wouldn’t have known that Blue Cranes’ numbers were declining or why. Through continued research, we will keep abreast of changes in the Blue Crane population and in the landscapes that they depend on.

The implementation of this four-pronged approach creates certainty for the EWT/ICF that we can reverse the decline in the Blue Cranes populations in the Karoo and Western Cape, as we have done in the Drakensberg region.

The EWT remains committed through the implementation of its Future Fit Strategy to working with partners throughout Africa to ensure the survival of crane species, particularly the Blue Crane. Grey Crowned Crane and Wattled Cranes.

** The EWT/ICF projects are generously supported by the Leiden Conservation Foundation, Eskom, Hall Johnson Foundation, Indwe Risk services, Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens Zoo Neuwied, Safari West, Nashville Zoo and the Paul King Foundation