A conservation success story – the return of the majestic Cape Vulture

Lindy Thompson and Danielle du Toit, the EWT’s Birds of Prey Programme

Cape Vultures (Gyps coprotheres) are endemic to southern Africa. They are one of South Africa’s larger vulture species, weighing up to 11 kg. They forage in open vegetation types such as Fynbos, Kalahari, Karoo, grassland, and open woodland. Breeding pairs are monogamous and usually raise one chick. The majestic Cape Vulture was listed as Endangered on the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species, but in 2021 it was ‘down listed’ to Vulnerable. This is a remarkable conservation success story and testament to the tireless efforts of multiple generations of conservationists in southern Africa. Removing the Cape Vulture from the list of Endangered species in 2021 received very little media attention, despite being an important case study that can provide hope and inspiration to current and future conservationists. This achievement resulted from a concerted effort by various organisations, including the Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT), BirdLife South Africa, and wildlife rehabilitation centres such as Moholoholo, VulPro, and others. A team of 31 contributors, which included the EWT’s Samantha Page-Nicholson) supplied information and justified why this species should (or should not) stay classed as ‘Endangered’. Threats to the species include unsafe wind energy developments, poisoning events, unsafe power lines, and food availability may play a large role in the successful breeding and population trends of this species. Current conservation actions for the Cape Vulture include systematic monitoring, education and awareness programmes, protection by national and international legislation, the expansion of formally protected areas (such as the Soutpansberg), and the creation and growth of Vulture Safe Zones.

The importance of Vulture Safe Zones in Cape Vulture conservation

Karoo Vulture Safe Zone Document

In India in the 1990s, vulture populations suffered drastic declines. Scientists were baffled as to why until the study of carcasses revealed the presence of the veterinary non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, Diclofenac. They concluded that this drug was the root cause of the mass fatality and had cost about 90% of the vulture population in the area in the space of a decade. This became known as “The Indian Vulture Crisis.” The disappearance of Vultures led to the ecological tipping of scales. Mammalian scavengers such as jackals and feral dogs took advantage of the increased food supplies, and their populations increased. The high number of mammals on carcasses inadvertently led to an increase in the spread of pathogens. India faced, and still faces, a rabies epidemic that costs 30,000 human lives per year and billions of dollars in health fees. The urgent need for action to stop the rapid decline of vulture species in Eurasia and Africa led to the development of the Multi-Species Action Plan to Conserve African-Eurasian Vultures (commonly referred to as the Vulture MsAP). It is a comprehensive and strategic plan which covers ranges across two continents. Vulture Safe Zones are an activity recognised in the Vulture MsAP to encourage the responsible management of the environment by actively reducing threats to vultures in identified areas. They are specified geographic areas where conservationists and landowners use targeted conservation measures adapted for the vulture species present. These measures include safeguarding electrical infrastructure to minimise collisions and electrocutions, reducing the use of poisons, covering or altering reservoirs to prevent vulture drownings, and using NSAIDs responsibly. The most important thing to remember is the responsible management of resources that vultures use, such as the availability of safe perches, water for drinking and bathing, and food. Vulture Safe Zones also promote responsible disposal of carcasses on which vultures scavenge to reduce poisoning through pesticides and lead fragments that remain in a carcass after an animal is shot.

The Karoo Vulture Safe Zone

Landowners in the karoo region of South Africa established the Karoo Vulture Safe Zone (KVSZ) to increase the area’s Cape Vulture populations that have been decimated by persecution resulting from misinformation and a general misunderstanding of their role in the ecosystem. Landowners in the mid-20th century believed that it was vultures killing their small livestock when they would find the birds feeding on them during the day. Unbeknownst to them at the time, the jackal population in the area was beginning to take advantage of the easy prey and kill them during the night. Now, the landowners in the area are admirably working to fix these past mistakes. In August 2020, the first landowner signed up to proclaim his property a Vulture Safe Zone. Since then, the KVSZ has grown to 730,000 hectares owned by 94 landowners committed to making their properties Vulture Safe. The project continues to encourage the responsible management of properties across the karoo landscape through landowner engagements and environmental education, which focus on sustainable and safe practices of managing predators and water resources and the safe disposal of carcasses. The KVSZ team also works through the strategic partnership between the EWT and Eskom to make problem powerlines safe for vultures. Cape Vulture sightings within the project area are reported to the KVSZ team, and it is exciting to receive reports of up to 70 birds roosting on cliffs that were previously void of these magnificent birds. Monitoring efforts by the team to better understand the populations traversing the Eastern Cape skies have shown an increase in breeding pairs in known sites and the possible development of new breeding sites. All of these give the team more motivation to make the Karoo and the larger Eastern Cape a safe space for Cape Vultures. The Vulture Safe Zone process is long, and it will take time until the area is completely vulture safe. In the interim, we continue to encourage vulture safe management and measures and spread awareness of the need for areas like this.

References:

Benson, P.C. and McClure, C.J. (2019). The decline and rise of the Kransberg Cape Vulture colony over 35 years has implications for composite population indices and survey frequency. Ibis 162: 863-872. https://doi.org/10.1111/ibi.12782 BirdLife International (2021). Gyps coprotheres. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021: e.T22695225A197073171. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T22695225A197073171.en accessed on 25 August 2022. Howard, A., Hirschauer, M., Monadjem, A., Forbes, N. and Wolter, K. (2020). Injuries, mortality rates, and release rates of endangered vultures admitted to a rehabilitation centre in South Africa. Journal of Wildlife Rehabilitation 40: 15-23. Mbali Mashele, N., Thompson, L.J. and Downs, C.T. (2022). Trends in the admission of raptors to the Moholoholo Wildlife Rehabilitation Centre, Limpopo province, South Africa. African Zoology 57: 56-63. https://doi.org/10.1080/15627020.2021.2016073 Thompson, L.J. and Blackmore, A.C. (2020). A brief review of the legal protection of vultures in South Africa. Ostrich 91: 1-12. https://doi.org/10.2989/00306525.2019.1674938

Poisoning poses a deadly risk to vultures in West Africa

Dr Lindy Thompson, the EWT’s Birds of Prey Programme

African vulture numbers are declining at an alarming rate, and their key threat throughout Africa is believed to be poisoning. One of the reasons people poison vultures is to obtain body parts, both for consumption and use in African Traditional Medicine. Dr Clément Daboné (from the Universities of Tenkodogo and Joseph Ki-Zerbo, both in Burkina Faso) collected information on incidents of mass vulture killings to learn more about the risk that poisoning poses to vultures in West Africa.

Dr Daboné conducted 730 interviews with butchers, veterinarians, foresters, and abattoir guards at numerous sites across Burkina Faso. His results revealed that vultures were killed in motor vehicle collisions and electrocutions at electricity poles, but poisoning was the deadliest threat to vultures in Burkina Faso. Out of 879 known vulture deaths, 779 were due to poisoning. Interestingly, Dr Daboné found that more vultures were more likely to be killed using poisoned baits closer to the country’s borders, suggesting that poisoning was being done by people from neighbouring countries. He concluded that the recent intentional vulture poisoning events in Burkina Faso were linked to the increasing demand for vulture parts in West Africa.

Dr Daboné and his team highlighted the need for awareness campaigns in local communities to teach people about the risks of using poison. They also mentioned the need for improved legislation and stronger commitment by West African governments to stop the trade in vulture body parts and prevent the extinction of these highly threatened birds and the services they provide.

Vultures face similar threats in southern Africa, and the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area is a wildlife poisoning hotspot. For this reason, the EWT’s Birds of Prey Programme has assisted in drafting South Africa’s new national Vulture Biodiversity Monitoring Plan, and we are providing Wildlife Poisoning Response Training to rangers so that they know how to identify, detect, and respond effectively to wildlife poisoning events by containing the crime scene and sampling carcasses for investigative purposes. Rangers are also trained on methods to save as many surviving birds as possible and decontaminate the scene to prevent further poisoning of animals or people. Together, we can make a difference.

The study was titled ‘Trade in vulture parts in West Africa: Burkina Faso may be one of the main sources of vulture carcasses’, and you can access it here: https://doi.org/10.1017/S095927092100054X

References:

Daboné, C., Ouéda, A., Thompson, L.J., Adjakpa, J.B. & Weesie, P.D.M. (2022) Trade in vulture parts in West Africa: Burkina Faso may be one of the main sources of vulture carcasses. Bird Conservation International. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095927092100054X

Gore, M.L., Hübshle, A., Botha, A.J., Coverdale, B.M., Garbett, R., Harrell, R.M., Krueger, S., Mullinax, J.M., Olson, L.J., Ottinger, M.A., Smit-Robinson, H., Shaffer, L.J., Thompson, L.J., van den Heever L. & Bowerman, W. (2020) A conservation criminology-based desk assessment of vulture poisoning in the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area. Global Ecology and Conservation 23:e01076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01076

A conservation success story – the return of the majestic Cape Vulture

Lindy Thompson and Danielle du Toit, the EWT Birds of Prey Programme

Cape Vultures (Gyps coprotheres) are endemic to southern Africa. They are one of South Africa’s larger vulture species, weighing up to 11 kg. They forage in open vegetation types such as Fynbos, Kalahari, Karoo, grassland, and open woodland. Breeding pairs are monogamous and usually raise one chick.

The majestic Cape Vulture was listed as Endangered on the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species, but in 2021 it was ‘down listed’ to Vulnerable. This is a remarkable conservation success story and testament to the tireless efforts of multiple generations of conservationists in southern Africa. Removing the Cape Vulture from the list of Endangered species in 2021 received very little media attention, despite being an important case study that can provide hope and inspiration to current and future conservationists. This achievement resulted from a concerted effort by various organisations, including the Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT), BirdLife South Africa, and wildlife rehabilitation centres such as Moholoholo, VulPro, and others. A team of 31 contributors, which included the EWT’s Samantha Page-Nicholson) supplied information and justified why this species should (or should not) stay classed as ‘Endangered’. Threats to the species include unsafe wind energy developments, poisoning events, unsafe power lines, and food availability may play a large role in the successful breeding and population trends of this species. Current conservation actions for the Cape Vulture include systematic monitoring, education and awareness programmes, protection by national and international legislation, the expansion of formally protected areas (such as the Soutpansberg), and the creation and growth of Vulture Safe Zones.

The importance of Vulture Safe Zones in Cape Vulture conservation

In India in the 1990s, vulture populations suffered drastic declines. Scientists were baffled as to why until the study of carcasses revealed the presence of the veterinary non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, Diclofenac. They concluded that this drug was the root cause of the mass fatality and had cost about 90% of the vulture population in the area in the space of a decade. This became known as “The Indian Vulture Crisis.” The disappearance of Vultures led to the ecological tipping of scales. Mammalian scavengers such as jackals and feral dogs took advantage of the increased food supplies, and their populations increased. The high number of mammals on carcasses inadvertently led to an increase in the spread of pathogens. India faced, and still faces, a rabies epidemic that costs 30,000 human lives per year and billions of dollars in health fees.

The urgent need for action to stop the rapid decline of vulture species in Eurasia and Africa led to the development of the Multi-Species Action Plan to Conserve African-Eurasian Vultures (commonly referred to as the Vulture MsAP). It is a comprehensive and strategic plan which covers ranges across two continents. Vulture Safe Zones are an activity recognised in the Vulture MsAP to encourage the responsible management of the environment by actively reducing threats to vultures in identified areas. They are specified geographic areas where conservationists and landowners use targeted conservation measures adapted for the vulture species present. These measures include safeguarding electrical infrastructure to minimise collisions and electrocutions, reducing the use of poisons, covering or altering reservoirs to prevent vulture drownings, and using NSAIDs responsibly. The most important thing to remember is the responsible management of resources that vultures use, such as the availability of safe perches, water for drinking and bathing, and food. Vulture Safe Zones also promote responsible disposal of carcasses on which vultures scavenge to reduce poisoning through pesticides and lead fragments that remain in a carcass after an animal is shot.

The Karoo Vulture Safe Zone

Landowners in the karoo region of South Africa established the Karoo Vulture Safe Zone (KVSZ) to increase the area’s Cape Vulture populations that have been decimated by persecution resulting from misinformation and a general misunderstanding of their role in the ecosystem. Landowners in the mid-20th century believed that it was vultures killing their small livestock when they would find the birds feeding on them during the day. Unbeknownst to them at the time, the jackal population in the area was beginning to take advantage of the easy prey and kill them during the night. Now, the landowners in the area are admirably working to fix these past mistakes. In August 2020, the first landowner signed up to proclaim his property a Vulture Safe Zone. Since then, the KVSZ has grown to 730,000 hectares owned by 94 landowners committed to making their properties Vulture Safe. The project continues to encourage the responsible management of properties across the karoo landscape through landowner engagements and environmental education, which focus on sustainable and safe practices of managing predators and water resources and the safe disposal of carcasses. The KVSZ team also works through the strategic partnership between the EWT and Eskom to make problem powerlines safe for vultures.

Cape Vulture sightings within the project area are reported to the KVSZ team, and it is exciting to receive reports of up to 70 birds roosting on cliffs that were previously void of these magnificent birds. Monitoring efforts by the team to better understand the populations traversing the Eastern Cape skies have shown an increase in breeding pairs in known sites and the possible development of new breeding sites. All of these give the team more motivation to make the Karoo and the larger Eastern Cape a safe space for Cape Vultures.

The Vulture Safe Zone process is long, and it will take time until the area is completely vulture safe. In the interim, we continue to encourage vulture safe management and measures and spread awareness of the need for areas like this.

You can help raise important funds for Cape Vulture conservation by supporting the Rhino Peak Challenge ambassadors, who aim to complete a 21 km course to ascend the famous Rhino Peak in the Maloti Drakensberg World Heritage Site. The Rhino Peak Challenge raises awareness and funds, for Wildlife ACT, the EWT, and Ezimvelo KZN Wildlife (EKZN), for projects focused on vultures, rhinos and cranes. The EWT’s Cath Vise will participate in the Rhino Peak Challenge this year. Cath manages the Protected Area Programme in the Soutpansberg, where there is a colony of nesting Cape Vultures. Please consider supporting Cath and the other Rhino Peak Challenge ambassadors by clicking this link:

https://rhinopeakchallenge.co.za/participants.aspx?participant=576715fb-a8b2-431e-807a-909ea6c39db4

References:

Benson, P.C. and McClure, C.J. (2019). The decline and rise of the Kransberg Cape Vulture colony over 35 years has implications for composite population indices and survey frequency. Ibis 162: 863-872. https://doi.org/10.1111/ibi.12782

BirdLife International (2021). Gyps coprotheres. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021: e.T22695225A197073171. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T22695225A197073171.en accessed on 25 August 2022.

Howard, A., Hirschauer, M., Monadjem, A., Forbes, N. and Wolter, K. (2020). Injuries, mortality rates, and release rates of endangered vultures admitted to a rehabilitation centre in South Africa. Journal of Wildlife Rehabilitation 40: 15-23.

Mbali Mashele, N., Thompson, L.J. and Downs, C.T. (2022). Trends in the admission of raptors to the Moholoholo Wildlife Rehabilitation Centre, Limpopo province, South Africa. African Zoology 57: 56-63. https://doi.org/10.1080/15627020.2021.2016073

Thompson, L.J. and Blackmore, A.C. (2020). A brief review of the legal protection of vultures in South Africa. Ostrich 91: 1-12. https://doi.org/10.2989/00306525.2019.1674938

Poisoning Risk to Vultures: A West African Crisis with Continental Implications

The poisoning risk to vultures has reached catastrophic levels in West Africa, where 89% of recorded vulture deaths result from deliberate poisoning. Dr Clément Daboné’s groundbreaking research in Burkina Faso reveals this alarming trend, with 779 of 879 documented vulture fatalities attributed to poisoned baits – particularly near national borders, suggesting transnational trafficking of vulture parts for traditional medicine.

Key Findings from Burkina Faso

- 730 interviews with butchers, veterinarians and abattoir staff

- Poisoning accounts for 89% of vulture deaths

- Border areas highest risk – indicating cross-border trade

- Secondary poisoning kills hundreds per incident

A Critically Endangered White-backed Vulture, Gyps africanus, photographed in South Africa’s Limpopo Province © L. Thompson.

Poisoning Risk to Vultures: Southern African Parallels

The crisis mirrors threats in the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area, where the EWT’s Birds of Prey Programme is taking action:

- Drafting South Africa’s Vulture Biodiversity Monitoring Plan

- Training rangers in Wildlife Poisoning Response

- Teaching crime scene preservation and carcass sampling

- Developing protocols to save surviving birds

“Each poisoning event can wipe out entire vulture colonies,” explains Dr Lindy Thompson. “We’re racing to build capacity before it’s too late.”

Urgent Conservation Measures Needed

-

Community awareness campaigns on poisoning impacts

-

Stronger legislation against vulture part trade

-

Cross-border cooperation to combat trafficking

-

Alternative livelihoods for traditional healers

With African vulture populations declining by up to 90% for some species, addressing the poisoning risk to vultures is critical to preventing ecological collapse across the continent.

A Critically Endangered subadult Hooded Vulture, which was poisoned, along with 64 other birds of prey, in South Africa’s Limpopo Province in 2015. © L. Thompson.

John Davies from the EWT’s Birds of Prey Programme talking about wildlife poisoning at Moholoholo Wildlife Rehabilitation Centre in South Africa’s Limpopo Province in 2020. © L. Thompson.

Dr Lindy Thompson (right), from the EWT’s Birds of Prey Programme, presented Wildlife Poisoning Response Training for the Black Mambas, an all-female anti-poaching force, in South Africa’s Limpopo Province.

The study was titled ‘Trade in vulture parts in West Africa: Burkina Faso may be one of the main sources of vulture carcasses’, and you can access it here: https://doi.org/10.1017/S095927092100054X

References:

Daboné, C., Ouéda, A., Thompson, L.J., Adjakpa, J.B. & Weesie, P.D.M. (2022) Trade in vulture parts in West Africa: Burkina Faso may be one of the main sources of vulture carcasses. Bird Conservation International. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095927092100054X

Gore, M.L., Hübshle, A., Botha, A.J., Coverdale, B.M., Garbett, R., Harrell, R.M., Krueger, S., Mullinax, J.M., Olson, L.J., Ottinger, M.A., Smit-Robinson, H., Shaffer, L.J., Thompson, L.J., van den Heever L. & Bowerman, W. (2020) A conservation criminology-based desk assessment of vulture poisoning in the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area. Global Ecology and Conservation 23:e01076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01076

Dr Lindy Thompson, the EWT’s Birds of Prey Programme

Science Snippets

Using an Ethogram as a guide to understanding Hooded Vulture breeding behaviour

Lindy Thompson, the EWT’s Birds of Prey Programme

Most vulture species are highly threatened, and their populations are declining. Researchers have been focusing more on vultures in recent years, and certain topics, such as their movements, are becoming well studied. However, other topics, such as how diseases affect vultures, and behavioural studies on vultures, have not been as popular. These areas need more attention because understanding all aspects of a species’ behaviour can help inform conservation efforts.

Studies on an animal’s behaviour can be enhanced using an ‘ethogram’. An ethogram clearly defines, describes, and classifies distinct behaviours commonly exhibited by a species. Researchers use ethograms as templates to record and understand the species’ behaviour. Importantly, ethograms can help to standardise data collection across different studies, which increases objectivity, and allows comparisons of results from different researcher teams.

Researchers from the Endangered Wildlife Trust and the University of KwaZulu-Natal recently produced the first ethogram describing the nesting and breeding behaviours of the Critically Endangered Hooded Vulture (Necrosyrtes monachus). They gleaned information from 14 Hooded Vulture nests in South Africa’s Lowveld region, from direct observations and over 400,000 camera photographs. The team described 28 behaviours exhibited by Hooded Vultures at their nests, and they grouped these behaviours into five categories: ‘Body Care’, ‘Movement’, ‘Nesting’, ‘Resting’ and ‘Social’. In their ethogram, the researchers also provided photographic records of each behaviour for researchers to use as references. Many of the behaviours exhibited by Hooded Vultures may be common to other tree-nesting vulture species, so this ethogram should be helpful for other research teams studying the breeding of other vulture species globally. It will also be used for further investigating the behaviour of Hooded Vultures in South Africa, and the next step is to look at activity budgets.

A juvenile Hooded Vulture on its nest in a Jackalberry tree. © L. Thompson/UKZN

The research team comprised the EWT’s Dr Lindy Thompson (the camera trap photos we used were collected during Lindy’s postdoctoral studies on Hooded Vultures), Prof. Colleen Downs (who supervised Lindy’s postdoc from the University of KwaZulu-Natal), and Fiona Fern, who is soon to start her PhD on raptor health with the EWT’s Birds of Prey Programme.

The study was funded by the Rufford Small Grants Foundation, GreenMatter, and the National Research Foundation (ZA).

The study was titled ‘An ethogram for the nesting and breeding behaviour of the Hooded Vulture Necrosyrtes monachus’, and you can access it here: https://doi.org/10.2989/00306525.2022.2072965

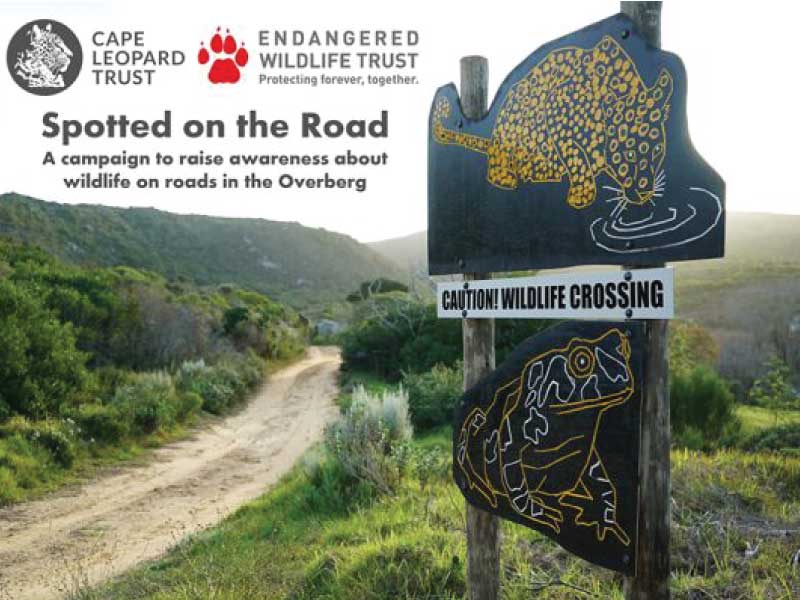

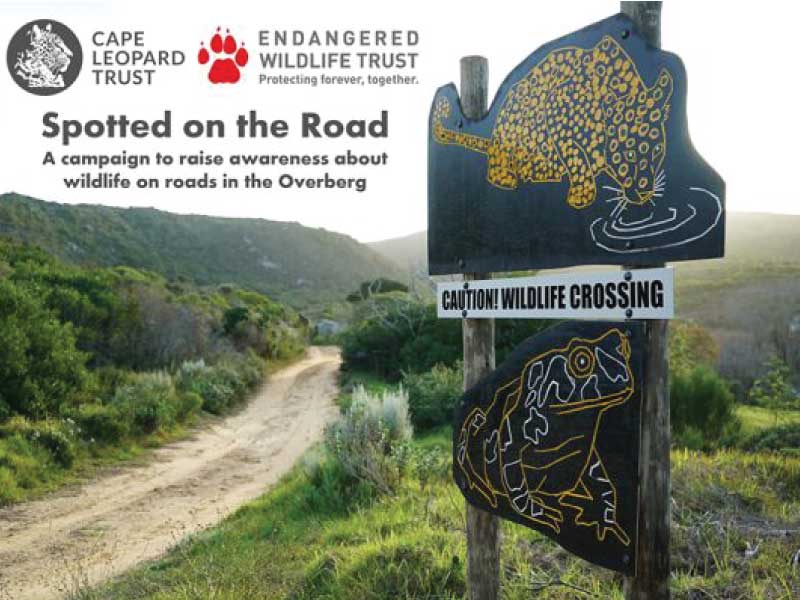

A campaign to raise awareness about wildlife on roads in the Overberg

Most people are familiar with the sad sight of dead animals on the side of the road, and many vehicle accidents in South Africa involve a collision with wildlife. Insurance claims suggest that approximately R82.5 million is paid each year in damages as a result of wildlife associated vehicle collisions. While actual collisions are the most obvious impact of roads on wildlife, other negative consequences include reduced air quality due to vehicle emissions, noise interference, and physical barriers to animal movement caused by the position of the road itself. Temporary road closures, wildlife crossings and bridges are means of improving safety for wildlife near roads, but the most common method is the use of roadside signs to warn motorists and mitigate wildlife-vehicle collisions. Signs installed in areas of high animal activity can help make drivers more aware of wildlife presence and ideally modify driving behaviour. With this in mind, the Cape Leopard Trust (CLT) and the Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT) have launched the ‘Spotted on the Road’ campaign to raise awareness about wildlife on roads in the Overberg. The campaign is part of the collaborative Tale of Two Leopards project (see links at the end of this document to read more), which focuses on two iconic species found in the Overberg region – the leopard and the Western Leopard Toad (WLT). Leopards and WLTs find themselves in an increasingly urbanised environment and must navigate through this transformed landscape, including crossing roads. The Endangered toads move en masse during their breeding season from July – September and when juveniles disperse in October. It is during these times that they are most vulnerable on roads. Leopards in the Cape have huge home ranges that are intersected by many roads, and leopards often cross roads in mountainous and natural areas, especially at night, putting them at risk of collisions with vehicles. The Tale of Two Leopards Spotted on the Road campaign worked with Cape Town-based artist Bryan Little to create reflective road signs of WLTs and leopards in an innovative move to alert motorists to slow down for these, and other animals on the roads, especially at night. The signs have been installed at five strategic locations in the Overberg, based on where WLT mortality by vehicles has been recorded previously and areas where camera traps have confirmed leopard movement. The locations vary between public and private land and tarred and dirt roads to maximise their reach. The signs were introduced to the public at an informal evening event held at Ou Meul Bakery and Café in Stanford on Saturday,16 July 2022. The Spotted on the Road evening featured an informative presentation, the unveiling of the signs, and an outdoor frogging experience at the Willem Appelsdam in Stanford. Contrary to the usual wet and windy weather that accompanies the Cape’s winters, the evening turned out to be calm, sunny and warm – perfect conditions for a nature walk to view the new reflective signs while listening out for different toad and frog calls around the dam. The CLT and the EWT sincerely thank the various landowners and the Overstrand Municipality who granted permission to host the new signs, as well Ou Meul Stanford for hosting the event, and Mountain Falls Spring Water for sponsoring its locally bottled water. The reflective road signs now join the interpretive Tale of Two Leopards information signboards to remind residents and travellers of the Overberg region’s amazing biodiversity. Please join us in our mission to protect it by making the roads of the Overberg safer for all wildlife!

Spotted on the Road Call to Action – How Can You Help?

- Drive slowly, especially at night

- Be on the lookout for animals on the roads

- Don’t swerve, but avoid collisions by reducing speed

- Help a toad cross a road (in the same direction in which it is travelling)

Be a citizen scientist and submit information!

- Contribute to leopard research by submitting photos of leopard sightings, signs like spoor or droppings, and threats to leopards to the CLT Western Cape leopard database: app.capeleopard.org.za

- As we move deeper into winter, the Western Leopard Toad breeding season is in full swing. This is an amazing time in the Overberg to see and hear this Endangered toad. Please share your WLT sightings with the EWT: inaturalist.org/projects/leopard-toads-of-the-overberg

Tale of Two Leopards news links:

Introducing the Tale of Two Leopards at the Tip of Africa Camera trapping for Overberg leopards in full swing! Overberg camera survey – success & highlights! Camera trapping in the Overberg – hefty hippos, baby birds & spotted cats! The Tale of Two Leopards in the Overberg – information signs & wildlife wines Released by the Cape Leopard Trust and the Endangered Wildlife Trust

For general / media information, contact:

Jeannie Hayward, CLT Communications and Media Manager, communications@capeleopard.org.za Emily Taylor, EWT Communications and Marketing Manager, emilyt@ewt.org.za

For research information, contact

Dr Katy Williams, CLT Research & Conservation Director, rcdirector@capeleopard.org.za Dr Jeanne Tarrant, EWT Threatened Amphibian Programme Manager, jeannet@ewt.org.za