How Cheetahs got their spot in the EWT’s history

How Cheetahs got their spot in the EWT’s history

Emily Taylor

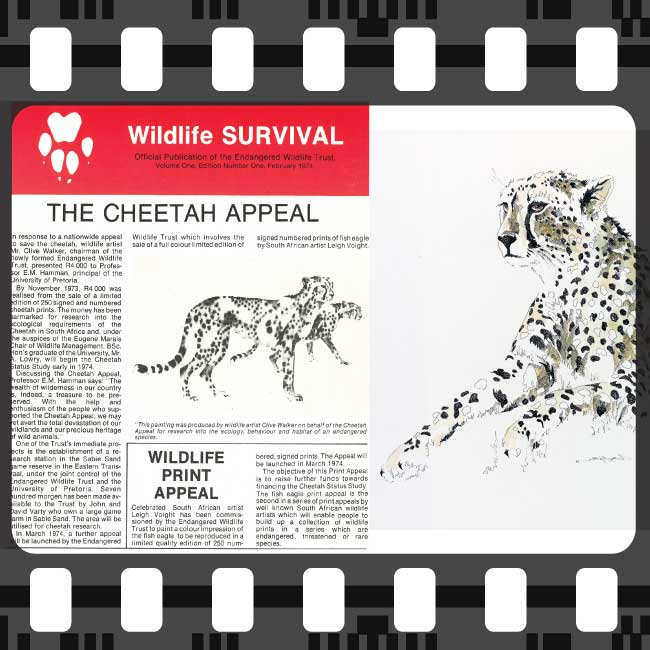

When Clive Walker raised funds for Cheetah conservation through the sale of his painting of two Cheetahs, he asked Koos Bothma, then associate professor of the Eugene Marais Chair of Wildlife Management at the University of Pretoria, if he would like to use the money for a Cheetah study. In 1973, the species was recognised as Endangered, both locally and internationally, and Koos quickly accepted. Clive was happy that the money could be channelled into a recognised institution.

Profile on Andrew Lowry featured on the contents page of an article about his research in African Wildlife, Volume 30, No. 6

Andrew Lowry was born and raised in Cape Town, South Africa. Having completed his BSc in Botany and Zoology at the University of Cape Town, Andrew went north to study for his Honour’s degree in Wildlife Management at Pretoria University, during which he won the Wildlife Society’s 1973 Bursary. Andrew was itching to get out into the bush and work with wildlife. He was available and in need of a research project, describing himself as a “spare” – someone without a specific project to focus on and thus available for any assignment by the department. Thus, the “spare” student was the perfect choice to be dispatched to Namibia for Cheetah research sponsored by the fledgling EWT.

At first, there was no specific location or Cheetah population to be prioritised for research. Andrew initially focused on farmland in Namibia where Cheetahs and other stock-raiding predators were being captured or killed. A game capture operator who was often called to remove Cheetahs from farms offered to share the information about where each Cheetah had come from. Andrew could then conduct Cheetah surveys in areas where Cheetahs were regularly seen. However, because farmers persecuted these predators, they were highly mobile and travelled large distances by night. It was also difficult for Andrew to cover the whole of Namibia on his own. In the three months that Andrew spent there, he saw not a single Cheetah and sought advice from James Clarke, co-founder of the EWT and wildlife expert, saying that the study was not viable, and he had nothing to show for his time and efforts. Instead, Andrew proposed a Cheetah study in Etosha National Park in Namibia. He had recently visited the park and seen Cheetahs as close as 300 metres from the gate. Etosha boasted the world’s largest free-living Cheetah population, and the then South West African (Namibian) Division of Nature Conservation and Tourism was eager to maintain this population and welcomed a formal research study in the park. Predator conservation is no easy task in a stock farming country like Namibia. Still, the awareness and concern of the authorities, coupled with information from field investigations such as this one, can help to ensure these animals’ survival. And so Andrew was tasked with conducting a census of the Cheetahs in the park, and in his words: “I rode through the gates of Etosha, and I landed in Paradise”.

For an accurate census, the first thing to do is to develop a reliable way to ensure that, when counting individual animals, you only count them once. Fortunately, each Cheetah’s spots are unique – like a human fingerprint, and once you have a record of their coat pattern, you can avoid recounting them. It is also a good way to identify animals when studying their behaviour and genetic diversity. Once an animal’s markings had been recorded, Andrew created the identity kit featured in Figure 1 to differentiate between individual animals. The EWT and other organisations still use similar methods to identify Cheetahs today. However, photos of animals are now run through software called Wildbook, ensuring identification is even more accurate than a human eye can achieve.

An identikit used by Andrew Lowry in his Cheetah study in Etosha in 1974-1976

Wildlife researchers are often advised not to give study animals names to maintain a level of objectivity. While this may work in theory, we often get attached to some or all of our subjects when we follow their lives so intimately. Andrew cheated a little. He did name each of the Cheetahs that he followed using a letter of the alphabet but then gave them names starting with these letters. In an article he wrote for the Wildlife Society of Southern Africa publication at the time, African Wildlife, Volume 30, No. 6, he explained: “For ease of recording in the field, I have allocated each animal a letter of the alphabet and have then given them a name meaning Cheetah, which begins with the same letter. Duma is the Swahili word for Cheetah. Others are Chita (the original Hindu word meaning “spotted one”), Etotongwe (Ovambo), Hlosi (Zulu), and Jubatus (the Latin species name). And let’s not forget Intermedius. Acinonyx intermedius is an extinct species of Cheetah which ranged in Europe and Asia during the middle Pleistocene.”.

In addition to his investigations and observations, Andrew appealed to visitors to the park to complete surveys describing any Cheetahs they came across and where in the park they were seen (Figure 2). This information supplemented his findings when he was unable to monitor the whole park. The appeal, in the form of a pamphlet visitors received at the entrance to the park, also served as an education and awareness-raising tool. The pamphlet provided some key facts about Cheetahs and sparked a new level of engagement among visitors – enriching their experience of the wildlife they came across. The use of non-scientists to collect data is more common now than it was then. Still, it has always been a valuable tool when conducting studies like Andrew’s. The Cheetah and Wild Dog Censuses that the EWT runs in the Kruger National Park, for example, are only made possible with the help of citizen scientists.

Pamphlet and survey form visitors received at the entrance to the park to provide additional data for the Cheetah study in Etosha National Park

During his two-year study of Cheetahs in Etosha, Andrew Lowry was immersed in their world, and when speaking of his time there, much of his focus, fascination, and awe was on the role of the female animal. She faces tremendous pressure alone once mating has taken place, and the male Cheetah leaves her to fend for herself and for her helpless cubs when they are born. Not only must she provide for them – she is responsible for teaching them to hunt and survive in treacherous surroundings. One female in Etosha, named Duma, impressed Andrew above others. In his article, Andrew writes:

“Duma has proved to be an exemplary mother. Not only does the survival rate of her litters appear higher than the Etosha average, but her offspring are capable hunters on parting company with her. We watched Acinonyx and her two brothers from shortly after they left Duma. If one of these Cheetahs began to initiate a hunt, the other two would perform outflanking stalks on either side of the potential prey animal. A more efficient trio I have yet to watch.”

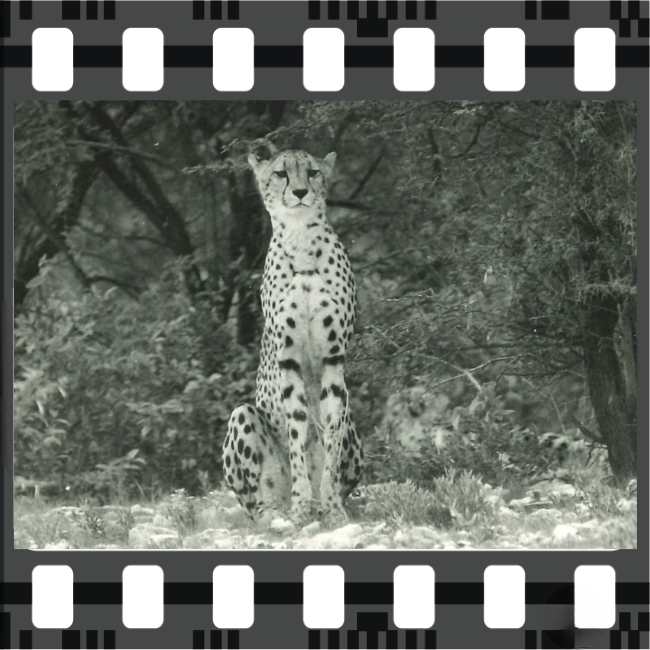

Duma, a particularly effective Cheetah mother studied by Andrew Lowry in Etosha in 1974 and 75

Read more about these cats in the full article here.

Learning much about Etosha’s Cheetahs, Andrew agrees with carnivore expert Dr R F Ewer that studies of predators are often only relevant to the time and place in which they occurred. He believes that studies of predators are usually only relevant to the time and place in which they occur and advised that the Cheetah numbers in the park were optimal at between 50 and 100 and that the low-density population would not benefit from further reintroductions – reiterating the original consensus that one of the largest remaining strongholds for Cheetahs in southern Africa should not be interfered with.

By the end of the study, the EWT had expanded. It was focused on rhino and elephant conservation while supporting other organisations also working on Cheetah conservation, such as the De Wildt Cheetah Centre. Andrew had for some time been increasingly concerned about the larger issues at play that were endangering all species, including humans. He knew where a difference needed to be made and went on to do so in the lecture halls of the Tshwane University of Technology. For 30 years, Andrew taught 21 subjects to around 3,000 students, six of whom currently work for the EWT, with many more doing so in the past. I was one of these students, inspired to work for the organisation within a month of my first year because Andrew believed in the work the EWT does so much that he included it in his coursework.

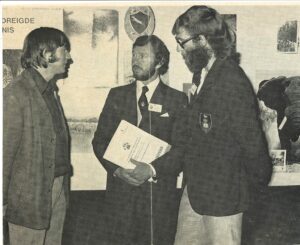

Clive Walker (centre), founder of the EWT, speaking to EWT carnivore researchers Gus Mills (left) and Andrew Lowry (right)

Now retired, Andrew makes an effort to follow the careers and personal journeys of his students, whom he considers family and fondly speaks of with pride. Refusing to have a cell phone, Andrew checks Facebook regularly, wishing students well in their personal and professional milestones. He was excited to hear from us and to visit the EWT Conservation Campus and tell us his story and catch up with those whose lives he touched so profoundly. A two-year study of a single population of Cheetahs in Etosha may not have had a significant short-term conservation impact, but it led both Andrew and the EWT to make unmeasurable and invaluable conservation impacts through their cultivation of countless conservationists who have and will still protect forever, together.