Roadkill remains a problem along South Africa’s major transport corridors

By Thabo Hlatshwayo, Wildlife and Transport Project: senior field officer, Endangered Wildlife Trust.

Although monitoring of the ecological impacts of transport infrastructure on biodiversity is still an emerging field of science in South Africa, it remains poorly supported in terms of funding. This is despite the fact that roads are responsible for the massive loss of biodiversity.

To determine the extent of roadkill in South Africa, the Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT) has been facilitating and supporting various road ecology research since 2011. From the data that we have gathered, it is clear that roadkill is prevalent.

South Africa’s road network covers around 750,000km. Our database on roadkill for the BAKWENA N1/N4, TRAC N4 and N3 toll routes indicates that a total of 8,569 records of wildlife roadkill incidences were reported from the three toll companies combined between 2012 and 2024. This is an increase of 1,565 from the roadkill magnitude reported in 2023, meaning that these animals were victims of roadkill on the toll route in 2024.

This emphasises the need for advancing biodiversity loss accounting in the transportation sector and crafting national transportation policies that are ecologically sustainable and support just transitioning to green transportation in South Africa. Supporting research on understanding how our road systems impact threatened habitats, habitat use and movement by animals is critical.

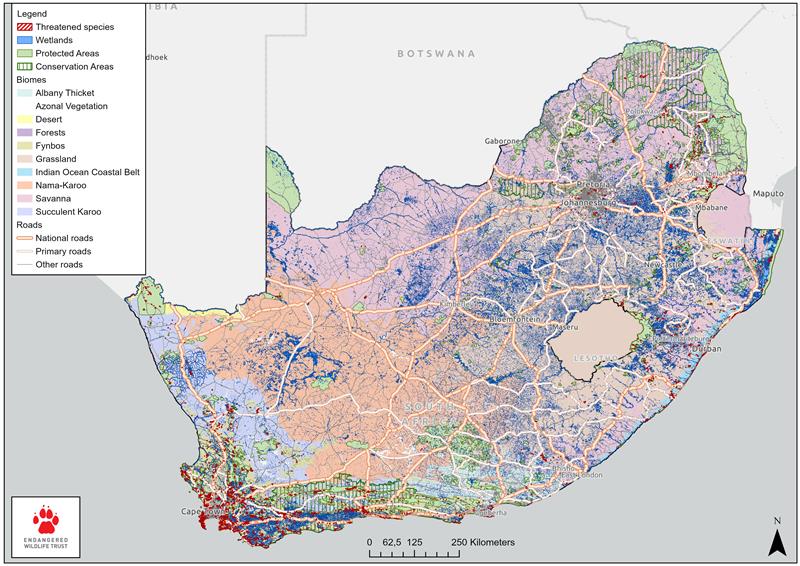

The construction and operation of transport corridors, such as roads and railways, have a range of both direct and indirect negative impacts on wildlife and natural ecosystems. Clearing natural landscapes for the construction of transport infrastructure causes vegetation cover loss, often leading to degraded landscapes. In the 28 years up to 2008, South Africa reportedly lost 0.12% of its natural vegetation cover per year as a result of massive linear infrastructure development, including transport corridors. Thus, all these contributed to landscape fragmentation, reduced land cover and connectivity loss for wildlife. It is interesting to note that the country’s roads stretch through sensitive habitats and wildlife hotspots, some of which are home to Threatened Species.

Habitat loss because of fragmentation is a primary threat to terrestrial biodiversity and could drive species extinction as it affects numerous endemic species. The fragmentation of a landscape limits the migration rates of species and its available habitat. Besides affecting migration patterns, it also contributes to inbreeding because species’ behavioural patterns, such as hunting, foraging, breeding and other home range activities have been disrupted. Habitat loss and fragmentation, because of transport corridors, also increases human-wildlife interactions. This leads to human-wildlife conflicts as animals are forced to cross roads for dispersal and migration. This further accelerates biodiversity loss through increased wildlife roadkill incidents, and numerous threatened species suffer the greatest risk from roadkill.

Small-to-medium sized mammals such as Serval, African Striped Weasel, Cape Clawless Otter, Honey Badger, Cape Porcupine, Cape Fox, African Wild Dog, several antelope and mongoose species are the most impacted mammal species. The reptiles that are most affected include Southern African Python, Puff Adder, Leopard Tortoises, Natal-hinged Tortoises, and Monitor Lizards. Among bird species, owls are the most affected, this includes the African Grass Owl, Barn Owl, Spotted-Eagle Owl and Marsh Owl.

However, we do come across incidents that involve large mammals like Hippopotamus and savanna buffalo along the N4, and Greater Kudu along the Bakwena N4 and N4, as well as cows. We have also recorded incidents that involved an Elephant and a Leopard along the R40 and R71 regional roads in Hoedspruit area.

Monitoring wildlife roadkill is the first step in understanding the impacts of roadkill on threatened species. By collecting data on roadkill, we can track mortality rates and distribution patterns of the roadkill of different species (where and to what extent). Studying these elements will expand our understanding of the ecological impacts of road infrastructure and traffic on wildlife movement. These will enable us to scientifically map conservation hotspots and further develop effective mitigation strategies to reduce these threats.

As much as we talk about roadkill becoming a threat to biodiversity, it is important to understand that the landscapes fragmented by road networks that intersect animal habitats are the core drivers for wildlife roadkill incidents across the globe. Changing climatic conditions influence animal movement patterns, causing numerous species to move frequently within their landscapes in search of important ecological resources. In an environment increasingly fragmented by road infrastructure, such movements could potentially result in a deathtrap for animals due to wildlife-vehicle collisions and a lack of connectivity corridors.

The EWT and the N3 Toll Concessionaire (N3TC), Trans African Concessionaire (TRAC) and Bakwena N1/N4 have trialed several roadkill-reduction methods for reducing the negative impacts on roads and highways on biodiversity. The first was to deploy temporary roadside fencing, directing wildlife to cross safely through underpasses such as drainage culverts. Camera traps were installed in several underpass structures that are located within hotspots to monitor whether wildlife used them, and we were excited to see that several mammals did. This includes Serval (Leptailurus serval), the most common animal killed on the N3. These results indicate that underpasses are a promising and cost-friendly alternative for wildlife crossing in a global south country like South Africa.

Preliminary results indicated increasing animal activity and the use of the underpass structures, with more mammal species appearing to use the structures that are retrofitted with mesh fencing; these include Serval, Southern Reedbuck (Redunca arundinum), Cape Clawless Otter (Aonyx capensis), Honey Badger (Mellivora capensis), and Common Warthog (Phacochoerus africanus). When more animals use the underpass structures to cross the highway, animal activity adjacent to the road is reduced; hence, reducing collisions whilst improving road safety.

Because owls and other raptors tend to use signboards and safety barriers along roads to perch on while hunting prey, such as rodents and squirrels, a second roadkill-reduction method has been tested. This has seen the EWT placing raptor perches 100 m from the road to encourage owls and other birds of prey to use these as safer alternatives and to reduce hunts on the roads. Cameras on the owl perches have recorded several birds of prey species using the installed perches for feeding or perching. This includes African Grass, Barn and Spotted Eagle Owls. Our findings showed that the more owls use the installed structures for hunting and feeding, their activity on the road is reduced.

South Africa’s road and rail network is essential for our socio-economic development through travel and tourism, and the transport of food and goods. It is therefore critical that solutions are found to reduce the impact of transport infrastructure on people and wildlife without hindering our transport sector.

Left: Camera Trap at Raptor Perch recording a African grass owl. Right: Black winged Kite Vs Pied Crow recorded at Raptor Perch

Modified Culverts for wildlife crossing

Wildlife and Transport Project

- The EWT is the only African organisation with a dedicated project focusing on transport and wildlife interactions.

- The project works across South Africa and collaborates on similar projects with colleagues worldwide.

- Our goal is to reduce the impacts of transport infrastructure on wildlife and vice versa. We focus on improving our understanding of the threats to wildlife from transport activities and infrastructure and identifying solutions suitable to the southern African context.

- In 2013, the EWT launched a smartphone app called “RoadWatch” – one of the first roadkill reporting apps in the world. To date, almost 30,000 data points have been reported via the app.

- The Endangered Wildlife Trust’s National Roadkill Database for South Africa shows that mammals are the most commonly-reported roadkill (50%), followed by birds (18%), reptiles (6%), and amphibians (1%), with 24% of species being unidentifiable.

- Large mammals, such as carnivores and antelope, are likely to cause damage or delays to trains and vehicles. Collisions with animals can be expensive with insurance claims suggesting that approximately R82.5 million is paid yearly against vehicle collisions with wild animals.

Roadkill map of South Africa

The EWT has provided support for a study that has developed a Drivers-Pressure-State-Impact-Response (DPSIR) framework of ecological connectivity in transport sustainability in South Africa. Because of the Framework, steps are being taken to help shape a sustainable transport sector that promotes robust monitoring and mapping of hotspots and the support of a consultation process to formulate policies that promote sustainable land-use planning by considering wildlife needs in green transport infrastructure planning frameworks in South Africa.

Unfortunate incidences involving large mammals