“Do Shrews Swim?” – A Field Diary from the Outeniqua Mountains

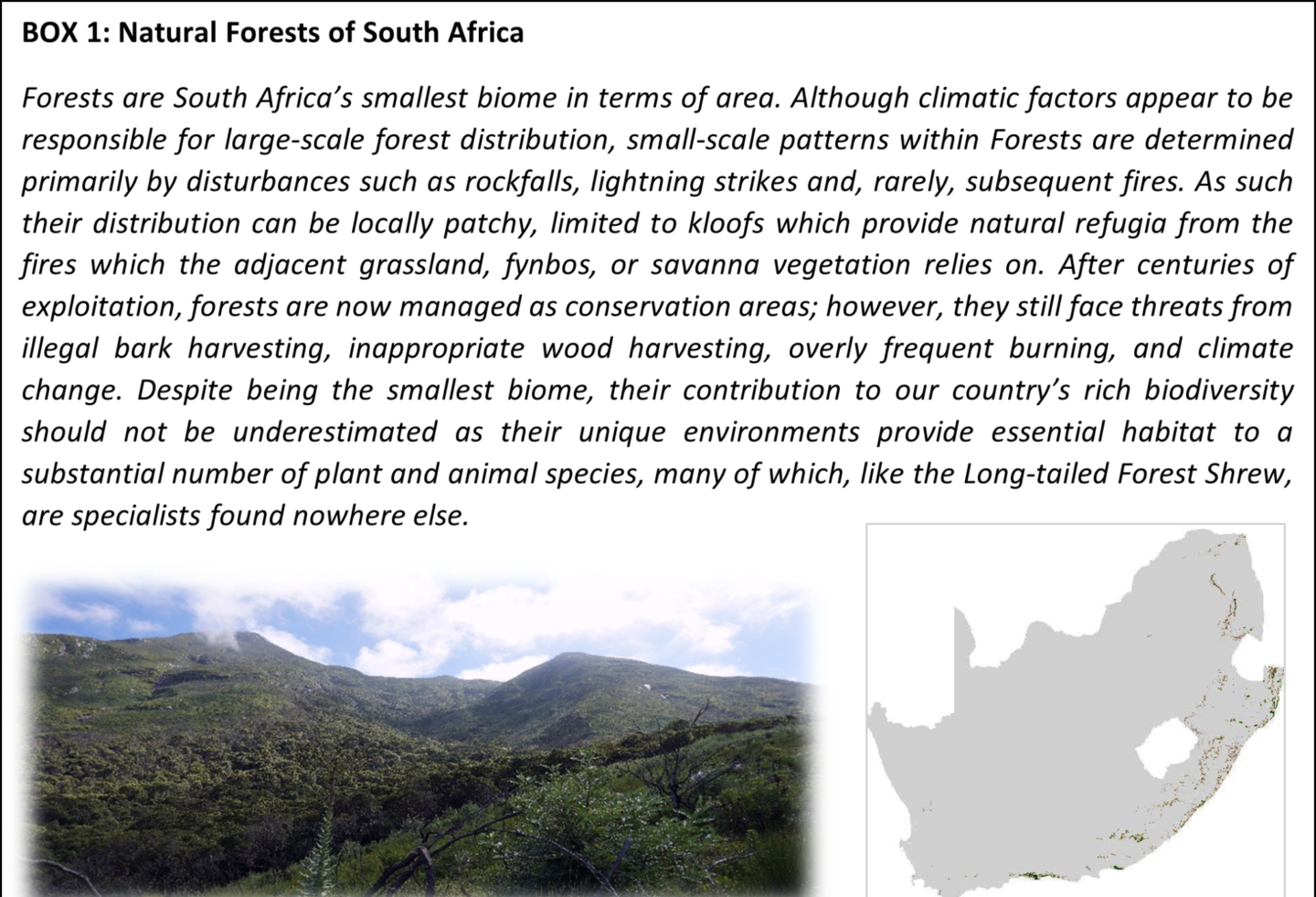

Do shrews swim? This unexpected question dominated my thoughts during recent fieldwork in the misty Outeniqua Mountains above George, where our team searched for the Endangered Long-tailed Forest Shrew (Myosorex longicaudatus) – not seen since the 1990s.

Dr Oliver Cowan, Conservation Science Unit, oliverc@ewt.org.za

Musk Shrew after a swim. Photo credit: Oliver Cowan

Musk Shrew after a swim. Photo credit: Oliver Cowan

Survey Methodology

Our team employed multiple techniques:

- 40+ Sherman live traps baited with peanut butter-Bovril-oats mix

- Camera traps placed along game trails

- Ultrasonic recorders for bat echolocation (Pettersson D500X)

- Microhabitat measurements (temperature, humidity, canopy cover)

- GIS mapping of all trap locations

Traps were checked at dawn and reset at dusk following strict ethical protocols. Each captured animal was:

-

Identified to species

-

Photographed for verification

-

Measured (weight, body/tail length)

-

Released unharmed at capture site

Notable Species Observations

Beyond the swimming shrew incident, we documented:

Mammals:

- Honey Badgers (Mellivora capensis) – First forest record via camera trap

- Cape Clawless Otter (Aonyx capensis) spraints along streams

- 4 bat species (new mountain records via ultrasonic analysis):

-

Cape Serotine (Neoromicia capensis)

-

Long-tailed Forest Bat (Myotis tricolor)

-

Egyptian Free-tailed Bat (Tadarida aegyptiaca)

-

Banana Bat (Neoromicia nanus)

Birds:

- Forest Buzzard (Buteo trizonatus) – Constant aerial observer

- Knysna Turaco (Tauraco corythaix) – Emerald flashes through canopy

- Olive Woodpecker (Dendropicos griseocephalus) – Drumming in yellowwoods

Herpetofauna:

- Table Mountain Ghost Frog (Heleophryne rosei) in streams

- Southern Adder (Bitis armata) coiled in leaf litter

Do Shrews Swim? The Swimming Shrew

The aquatic surprise occurred during a lunch break:

-

Heard splash in forest stream

-

Discovered flailing Lesser Dwarf Shrew (Suncus varilla)

-

Documented rare swimming behaviour (3 minutes observation)

-

Rescue via tail-lift to prevent hypothermia

-

15-minute rewarming in cotton shirt before release

“This challenges assumptions about shrew ecology,” noted Dr. Cowan. “Their aquatic capabilities may explain how they colonise isolated forest patches.”

Verraux’s Mouse (left), Striped Mouse (top right), and Lesser Dwarf Shrew (bottom right). Photo credit: Oliver Cowan

Verraux’s Mouse (left), Striped Mouse (top right), and Lesser Dwarf Shrew (bottom right). Photo credit: Oliver Cowan

Future Expedition: Boosmansbos Wilderness

Plans are underway for a 7-day expedition to survey this remote area:

Logistics:

- 15km hike-in with all equipment

- Base camp at 1,200m elevation

- Helicopter support for heavy gear (pending funding)

Target Species:

- Critically Endangered Boosmansbos Forest Shrew subpopulation

- Micro Frog (Microbatrachella capensis) in wetland areas

- Historical records of Acontias lizard species

Innovative Methods:

- Environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling of streams

- Thermal imaging cameras for nocturnal surveys

- Automated recording units for avian monitoring

Conservation Implications

These findings:

- Update species distributions for IUCN assessments

- Reveal forest connectivity patterns

- Highlight need for protection of isolated patches

- Demonstrate value of mixed-methodology surveys

As I write by headlamp, the Forest Buzzard’s final evening call echoes through Tonnelbos – a reminder that these mountains still hold secrets waiting to be uncovered.

Our lunch spot in the Kloof. Photo credit: Oliver Cowan

Our lunch spot in the Kloof. Photo credit: Oliver Cowan

The ever-watchful Forest Buzzard. Photo credit: Oliver Cowan

The ever-watchful Forest Buzzard. Photo credit: Oliver Cowan