The Fragility of Africa’s Lions

The Fragility of Africa’s Lions

Samantha Nicholson, the EWT’s Carnivore Conservation Programme

The African Lion (Panthera leo) is an iconic and culturally significant species, valued by both global public sentiment and local communities in many regions. Lions hold ecological value as apex predators, with their removal from ecosystems leading to adverse and long-lasting ecological consequences. Additionally, lions contribute to the economies of countries through tourism, attracting both photographic tourists and trophy hunters.

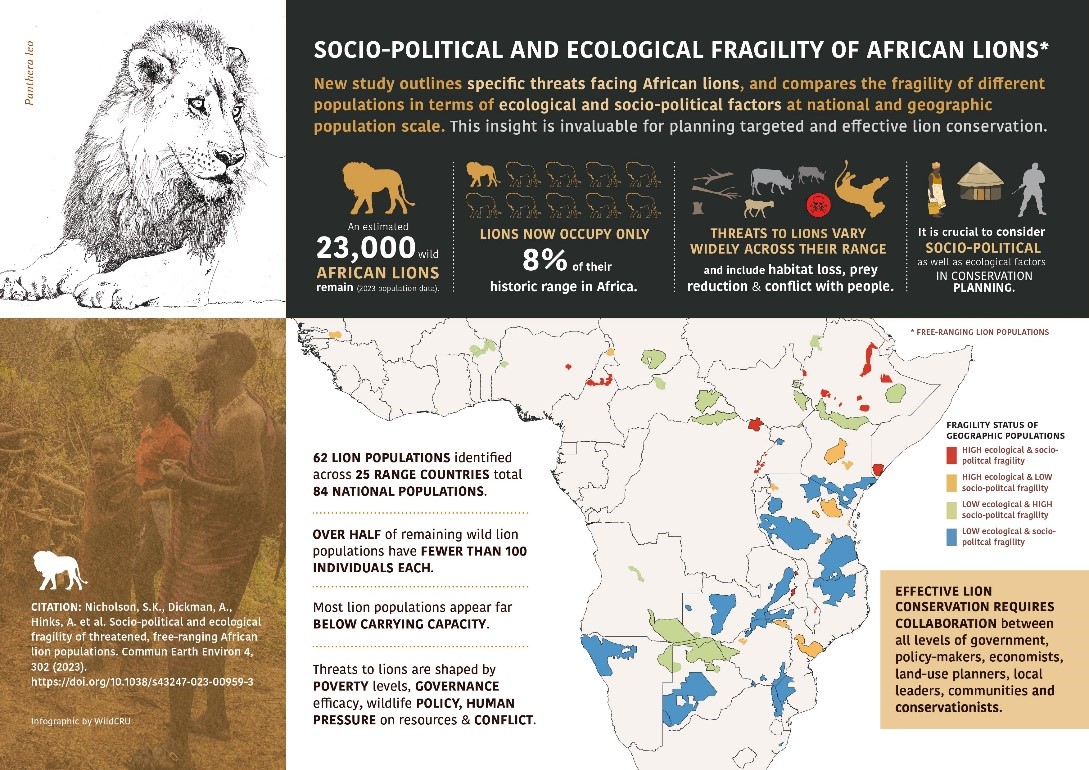

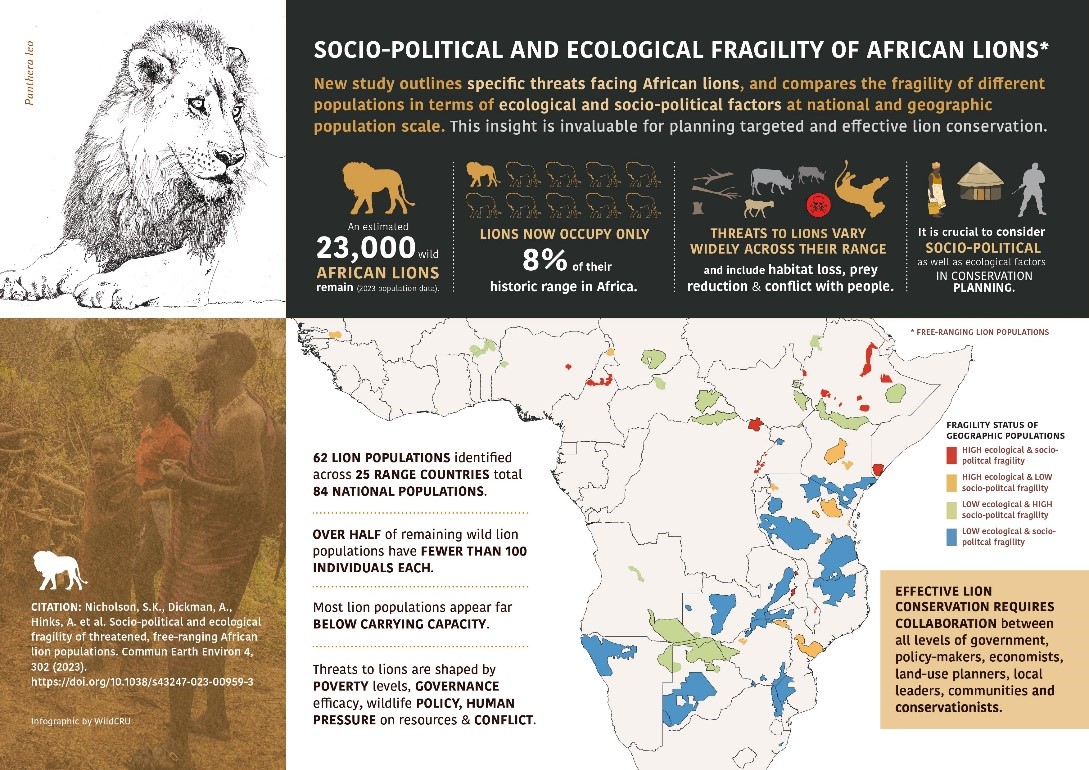

However, lion populations have dramatically declined over recent decades, with the most recent estimates suggesting 20,000 to 25,000 wild lions remaining in Africa, and they have been extirpated from 92% of their historical range. As such, effective conservation efforts are urgently needed, but the lack of comprehensive knowledge about specific threats and the socio-political contexts has hindered progress. The underlying drivers of lion threats are complex, involving socio-political factors such as poverty, governance (including corruption), wildlife policies, human pressures, and armed conflicts.

A recent study conducted a comprehensive assessment of the fragility of lion populations across their African range, considering both ecological and socio-political factors. The study first identified and mapped wild African Lion populations. The researchers then created two general categories of population fragility, ecological and socio-political, and identified factors in these two categories that may influence the survival of wild lions. For example, a smaller lion population or higher densities of people and livestock were factors contributing to higher ecological fragility, while higher corruption or lower GDP per capita would contribute to greater socio-political fragility. Once calculated, both socio-political and ecological factors were combined into a single overall fragility index, and each lion population was compared relative to all others. The fragility score does not suggest which lion populations deserve protection or funding. It does, however, highlight the varying ecological and anthropogenic pressures facing different population and which populations may require relatively more resources (financial or other) to conserve.

How you can help our cause:

DONATE VIA EFT:

The Endangered Wildlife Trust

FNB Rosebank (Branch code: 253305)

Account number: 50371564219

Use Reference: CCP LIONS

The combination of these two indices provided some interesting comparisons. Some populations may ultimately have similar fragility scores, but they are driven by different threats. Thus, while on the surface, the lone lion populations in Sudan and Benin may appear similar, they likely require different levels of investment and perhaps even different types of intervention for conservation to succeed. Pouring money into conserving Sudan’s lions may be relatively ineffective unless the socio-political factors such as the civil war are dealt with first. Thus, stakeholders, investors and conservation groups must be aware of these differences when approaching lion conservation and evaluating how much money, time or other investment may be needed to see success.

Our study revealed that Maze National Park in Ethiopia was identified as the most ecologically fragile population at both a geographic and national level. This can largely be attributed to intense edge effects from high densities of both cattle and people. When assessing at the national level, Cameroonian and Malawian lion populations were most ecologically fragile due to their small populations and isolation from other lion populations. Somalia was the most fragile lion range country from a socio-political perspective. Maze National Park and Bush-Bush (Somalia) were found to be the most fragile overall when ecological and socio-political fragility scores were combined.

Conservation is needed more than ever. Our study showed less than half of the 62 known remaining free-ranging wild African Lion populations have over 100 lions. African Lions remain in only 25 countries and nearly half of these nations have fewer than 250 individuals. Eight countries now house only a single wild lion population. Although lions are estimated at between 20,000 and 25,000 individuals, there is concern that these small populations and countries with few individuals will disappear.

These findings emphasize the need for more nuanced and precisely targeted lion conservation plans, considering both ecological and socio-political dimensions. As lions teeter on the brink of extinction, this research serves as a vital resource for informed conservation efforts. By considering ecological and socio-political factors, this model offers insights into factors affecting population persistence and successful conservation action.

Nicholson, S.K., Dickman, A., Hinks, A. et al. Socio-political and ecological fragility of threatened, free-ranging African lion populations. Commun Earth Environ 4, 302 (2023).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00959-3

This project is a partnership between the EWT, South African National Parks (SANParks), National Administration of Conservation Areas in Mozambique (ANAC), and the Peace Parks Foundation, with funding from the UK Government, through the International Wildlife Trade Challenge Fund.

This project is a partnership between the EWT, South African National Parks (SANParks), National Administration of Conservation Areas in Mozambique (ANAC), and the Peace Parks Foundation, with funding from the UK Government, through the International Wildlife Trade Challenge Fund.