Synergies and Trade-Offs in the effort to save our natural world: the Global Biodiversity Framework, the Sustainable Development Goals and the Climate Action Goals

Namita Vanmali and Ian Little

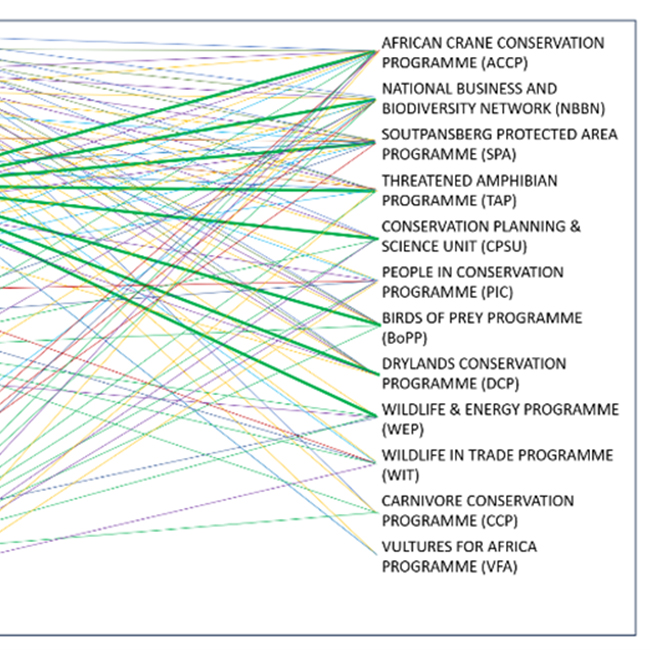

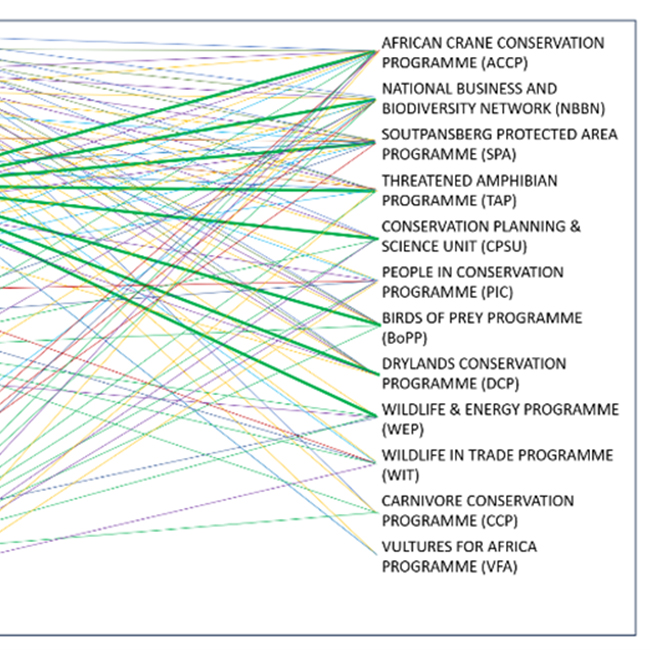

An illustration of the multiple linkages and alignment between the EWTs programmes and the Global Biodiversity Framework targets, with the specifically climate change relevant links in bold green.

Climate change is now widely recognised as a key driver of biodiversity loss, and although they are inextricably linked, historical approaches to policies addressing biodiversity loss and climate change have often treated these challenges separately. This divergence traces back to the independent conventions established during the 1992 Rio Earth Summit—namely, the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Over time, an increasing alignment of mechanisms within these frameworks and recognition of the impacts of climate change on biodiversity has allowed for better integration of strategies and enabled a more holistic approach to addressing these associated challenges. A significant milestone in this integration occurred recently at COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, where specific sections were dedicated to oceans, forests, and agriculture for the first time. This cross-pollination of strategies is paramount in achieving the objectives of climate mitigation and biodiversity conservation. “Nature-based solutions” (NbS) have been put forward as a unifying mechanism for achieving conservation and climate goals, underscoring the importance of safeguarding both environmental and social interests. The IUCN defines NbS as “actions to protect, sustainably manage, and restore natural and modified ecosystems that address societal challenges effectively and adaptively, simultaneously benefiting people and nature. They target major challenges like climate change, disaster risk reduction, food and water security, biodiversity loss and human health, and are critical to sustainable economic development”.

The Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF – 2022) provides a comprehensive roadmap for biodiversity conservation for the coming decade, outlining actions to halt biodiversity loss and promote sustainable ecosystem management. Comprising 23 action-oriented global targets to be achieved by 2030, it serves as a critical milestone on the journey toward overarching biodiversity conservation goals. Targets 1-8 focus on reducing threats to biodiversity, 9-13 emphasise meeting people’s needs through sustainable use and benefit sharing, and targets 14-23 focus on providing tools and solutions necessary to implement the GBF effectively. By addressing threats to biodiversity and boosting ecosystem resilience, GBF Targets 1-8 strongly align with goals for climate change adaptation, with target eight specifically focussed on minimising the impacts of climate change on biodiversity. There is an emphasis on expanding protected areas, halting species losses and managing invasive species impacts using holistic climate strategies. GBF Targets 2, 10, 11, 15 and 16 all align with climate change adaptation goals by emphasising sustainable resource use, ecosystem restoration and improving ecosystem service provision. While GBF Targets 13-23 emphasise the integration of biodiversity considerations into various sectors, policies, and resource mobilisation efforts, which aligns with climate change mitigation and adaptation goals.

How you can help our cause:

DONATE VIA EFT:

The Endangered Wildlife Trust

FNB Rosebank (Branch code: 253305)

Account number: 50371564219

Use Reference: Climate Action

An illustration of the multiple linkages and alignment between the EWTs programmes and the Global Biodiversity Framework targets, with the specifically climate change relevant links in bold green.

While there is obvious synergy between the targets of biodiversity conservation and climate change mitigation and adaptation, there can be

misalignments and tensions between the two. Conflicting land use priorities may cause trade-offs between GBF Targets and climate goals. While GBF Targets 1, 2 and 3 concentrate on spatial planning and ecosystem restoration, achieving climate goals may require land for

renewable energy infrastructure and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) projects requiring large-scale land use, which can and does conflict with biodiversity conservation efforts. The EWT has developed a number of

resources to guide and streamline decision-making to minimise these biodiversity conflicts, and strongly

supports renewable energy as opposed to the continued use and extraction of fossil fuels. Further, since climate action goals prioritise carbon sequestration to meet emission reduction goals, current reforestation and afforestation practices can negatively impact biodiversity if restored ecosystems serve climate mitigation instead of biodiversity conservation. Targets 8–13, which concentrate on sustainable resource use for people, can be at odds with critical Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Restricting access to resources in protected areas, for instance, may impede Poverty Reduction and Zero Hunger SDGs in some communities that rely on the land for agriculture or resource extraction. This conflict is also seen within the GBF targets 5 (Ensure the sustainable use and trade of wild species) and 9 (Protect & encourage customary sustainable use), where traditional use of wildlife resources is very often difficult to manage sustainably as a result of high demand for threatened resources and socio-economic pressures on rural communities.

While GBF Targets 14-23 theoretically align with implementation methods for climate change adaptation, challenges arise in practice where socio-economic pressures and needs conflict with conservation priorities and resource allocations. These challenges include potential competition for resource allocation, funding, land use and opposing interests within various sectors. Balancing short-term economic gains with long-term environmental benefits remains a complex and nuanced task. Integrated strategies that control possible conflicts are required to navigate these trade-offs successfully. The GBF targets and climate action goals both seek a just transition towards sustainability. However, misalignment between the GBF targets, climate adaptation, and SDGs often stems from divergent priorities between emission reduction, environmental preservation and broader development objectives.

Globally the financial cost of the transition to renewable energy dwarfs the funding required for biodiversity conservation. While it is imperative that the world prioritises a move away from reliance on fossil fuels, it is equally important that we recognise the parallel importance of conserving our biodiversity assets. The global narrative around the protection of our environment and commonly used terms like “Nature-based Solutions” should not allow the energy transition agenda to overshadow the biodiversity conservation crisis in terms of financial resource allocation and ongoing global dialogue

Mission (im)possible: Documenting all the Biodiversity on Papkuilsfontein

Bonnie Schumann, the EWT’s Dryland Conservation Programme Senior Field Officer

The Endangered Wildlife Trust recently conducted a comprehensive biodiversity survey on the Papkuilsfontein proposed Protected Environment. Papkuilsfontein is situated near Nieuwoudtville in the Northern Cape in a region known for its rich and unique biodiversity. However, the official list of species recorded on this property contains less than 300 species, and hence our mission was to rectify this and kick-start building a list that would accurately represent the incredible biodiversity found on this property.

Papkuilsfontein, owned by the Van Wyk family, is currently being declared as a formally Protected Environment in collaboration with the EWT and the Department of Agriculture, Environment, Land Reform, and Rural Development (DAERL). Following the survey, the species list now stands at over 1,300 species, and this is just the beginning!

The Bokkeveld Plateau is an area where three biomes meet, the Fynbos, the Succulent Karoo, and the Hantam Karoo. Combined with the variation in altitude, topography, and geology, this creates ideal conditions for the incredible evolution of species and diversity in the region. Nieuwoudtville is world-famous for its bulb plant diversity and density, with over 20,000 bulbs recorded per square meter. Research on the array of invertebrates associated with plant diversity has only started to scratch the surface. So the task of recording all things great and small over approximately 7,000 ha was a formidable one and will take several years to come close to accomplishing!

The EWT enlisted the help of a group of volunteers passionate about conservation to tackle this enormous task. The Custodians of Rare and Endangered Wildflowers, ably led by Ismail Ibrahim and comprising a team of students from the University of Stellenbosch Botanical Gardens, answered the call. Retired small mammal expert, Dr Guy Palmer, was put back to work, while Handré Basson was persuaded to abandon his studies for a few days and join us, bringing his passion for invertebrates and skill at finding them to the team. We were privileged to have had Dr Michael Kuhlmann, a world-renowned expert on solitary bees, join us for two days. Thanks to Dr Kuhlmann’s dedicated work on the plateau over the years, we know that Papkuilsfontein alone has an impressive list of over 100 species of solitary bees. Many of these are not yet described, and new species are still waiting to be discovered!

The EWT supplied the transport, and the Papkuilsfontein hospitality staff kept the team well-fed on some of the best hearty farm-style meals in the Karoo. Teams worked from dawn to dusk, scouring the rugged terrain and photographing and recording as much as possible. A camera trap survey was also conducted for six weeks, and tiny amounts of soil were collected for researchers to examine for environmental DNA later. Observation gathered from all three methodologies will contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the biodiversity present on the property.

The DAERL Stewardship Unit was instrumental in making the survey a success. A member of the unit, and ex-EWT staff member, JP le Roux, set up an iNaturalist project for the study and continues to work hard in the field to make sure the list of species keeps growing. iNaturalist is an online social network platform where people interested in biodiversity can share information. Anyone who sees an interesting plant or animal can photograph and upload the sighting to the platform, and a range of specialists are available to help identify the sighting. By setting up a project on the platform, all sightings made on the property can be collated, and species lists can be exported. The four-day survey provides just a glimpse of what is on the property. By having visitors and landowners take part in recording biodiversity using iNaturalist, we can ensure that a range of wildlife is captured, including plants and invertebrates, some of which may only make their appearance briefly every few years when conditions are just right for them. This makes recording the full spectrum of biodiversity at any location more achievable.

The region is special in terms of biodiversity and natural beauty. The EWT would like to thank all the landowners on the Bokkeveld Plateau who have a long-term vision to protect these features by declaring their properties as protected areas. This requires a high level of dedication at a very personal level in a day and age where talk is often cheap. Remember that Papkuilsfontein is not just an outstanding guest farm but is also a small commercial stock and rooibos tea producer. This conservation initiative is a great example of what can be achieved when the agricultural sector joins with the conservation sector to protect our natural resources at all levels.

The work on Papkuilsfontein was made possible with generous support from the Table Mountain Fund.

For more information:

EWT AND BUSINESS FOR NATURE CALL ON COMPANIES TO HELP REDUCE NATURE LOSS IN THIS DECADE.

Dr Gabi Teren, EWT’s Business and Biodiversity Network, Programme Manager gabit@ewt.org.za Healthy societies, resilient economies, and thriving businesses rely on nature. The natural resources that power businesses are under huge strain and the private sector is a major contributor to nature’s depletion. The Endangered Wildlife Trust’s National Biodiversity and Business Network (NBBN) has joined Business for Nature, a global coalition that brings together business and conservation organisations and forward-thinking companies. Together we amplify a powerful leading business voice calling for governments to adopt policies now to reverse nature loss this decade.

The Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT) recognised the need for a body to assist businesses to integrate biodiversity into their strategies and activities and established the NBBN in 2013, in partnership with the Department of Environmental Affairs (now the Department of Environment, Forestry, and Fisheries), and leading SA companies such as De Beers, Pam Golding Properties, Nedbank Limited, Hatch, Pick n Pay, and Transnet. In 2016, the list of NBBN partners grew to include Woolworths and Eskom. The NBBN aims to reduce the impacts businesses in South Africa have on nature by developing and disseminating relevant tools and guidelines to enable a more positive relationship with nature.

Businesses depend on a healthy planet to provide a stable operating environment, customers, and workforces, and the natural resources necessary for production – food, fibre, water, minerals, building materials, and more.

Nature also provides ecosystem services worth at least US$125 trillion/year globally, from which businesses benefit at no cost through, for example, waste decomposition, flood control, pollination of crops, water purification, carbon sequestration, and climate regulation. Losing nature means losing these services and creating extra costs and vulnerability for businesses. In fact, more than half of the world’s GDP – an estimated US$44 trillion of economic value generation – is moderately or highly dependent on nature and its services.

Leading businesses are making ambitious commitments and taking decisive action for nature. Businesses have a critical role to play in reversing nature loss, protecting biodiversity, and preserving species, and business action is about more than a responsibility – there are real and material risks associated with nature’s decline.

Businesses that act now to achieve net-zero and become nature-positive across their value chains will gain a competitive advantage.

In October this year, a new global agreement on nature called the ‘Global Biodiversity Framework’ is due to be agreed at the 15th Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD COP15) in Kunming, China. An ambitious, clear, implementable, and enforceable international agreement at COP15 will help realise nature’s true value to livelihoods, society and our economy.

But businesses cannot address this global crisis on their own. To accelerate action, governments must set ambitious nature and climate policies that provide direction and momentum. This gives the private sector clarity to unlock new business opportunities and creates a level playing field and stable operating environment. Hundreds of companies representing trillions in combined revenue are urging governments to adopt policies now to reverse nature loss through the Nature Is Everyone‘s Business Call to Action.

Whether you are a global corporate giant, an SMME or a sole practitioner, you can sign up your company today to the Call to Action, and join over 700 businesses from around the world who are calling for ambitious and collective action for nature. Companies of any size, location or industry can add their voice.

Sign up here: bit.ly/BfNCTA

For more information on the EWT’s National Biodiversity and Business Network, contact Gabi Teren GabiT@ewt.org.za

MANDELA DAY CAMPAIGN – 67 THINGS IN 67 DAYS – IT’S NEVER TOO LATE TO START!

In 2009, a study published in the European Journal of Social Psychology, by Phillippa Lally and colleagues from University College London, found that it took 96 subjects about 66 days for a new behaviour to become automatic.

If it takes 66 days for a new behaviour to become a habit, we will give you 67!

We know that many people were unable to venture out and help your community safely this Mandela Day and didn’t feel as though they did enough this year. For this reason, EWT created the 67 things campaign, which is a challenge to you to do one or more of 67 acts to change the world, for 67 days. If practiced regularly for 67 days, your actions can have a positive impact on people, our planet, and could become the habits that help save our future! Even though Mandela Day has passed, it is never too late to do your bit to build a better future. The acts we have identified have been categorised into the following six categories: Conservation support, Energy saving, Environmental impact, Kindness, Sustainable use, and Water saving.

If you do even one of these acts for 67 days, and this becomes a way of life, your impact can be lifelong.

You’ll never change your life until you change something you do daily. The secret to success is found in your daily routine.

– John C. Maxwell

SUBURBAN BLISS FOR BIODIVERSITY

Dominic Henry, Ecological Modelling Specialist, EWT Conservation Science Unit (CSU)

Reference: Chamberlain, D.E., Reynolds, C., Amar, A., Henry, D.A.W., Caprio, E. & Batáry. 2020. Wealth, water and wildlife: landscape aridity intensifies the urban Luxury Effect. Global Ecology & Biogeography. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/geb.13122

Biodiversity plays an important role in urban ecosystems and restricted access to it can profoundly affect human wellbeing. Unfortunately, urban dwellers rarely have equal access to biodiversity. Ecologists studying urban ecosystems have in many cases revealed a pattern whereby wealthier neighbourhoods in many cities have higher levels of biodiversity than poorer areas – a phenomenon that scientists have called the “Luxury Effect”. The Luxury Effect is indicative of environmental injustice, as the benefits associated with biodiversity are not shared equitably across society.

A new study published in Global Ecology & Biogeography by an international team of scientists from the University of Turin in Italy, the University of Cape Town and the University of Witwatersrand in South Africa, and the Centre for Ecological Research in Hungary, and co-authored by EWT staff member Dominic Henry, conducted a meta-analysis (an analysis that combines the results of multiple scientific studies) to determine the generality of the Luxury Effect and identify factors that drive variation in this pattern. The authors tested the Luxury Effect across 96 studies from around the world that examined the relationship between socioeconomic status and biodiversity.

The authors found that there was a significant positive relationship between terrestrial biodiversity (including the abundance and species richness of plants, birds, reptiles and insects) and the level of wealth in a city, confirming the existence of a global luxury effect. An interesting finding was that this relationship was far more prominent in the drier regions of the world suggesting that the Luxury Effect could partly be driven by water availability. Wealthier people living in more arid regions may invest more in water features, such as ponds or swimming pools, or in irrigation of their gardens and parks. Alternatively, wealthier areas may be associated with wetter areas within these arid landscapes, with higher property prices associated with lakes, rivers, or other wetland features.

The relevance of this finding in a South African context is profound given how city planning under the apartheid government fell along racial lines. Within cities, most black South Africans continue to live on the periphery in areas where the land is degraded, and often within close proximity to industrial sites where access to clean air and water are limited. Understanding the finer details of the mechanisms that drive and maintain the Luxury Effect can help with the creation of more equitable cities in the future. Acknowledging that access to biodiversity is an incredibly important part of our lives can help facilitate the management of urban areas to make access to the benefits of biodiversity more equal across the socioeconomic spectrum.