Vervet Monkey

Chlorocebus pygerythrus

2025 Red list status

Least Concern

Regional Population Trend

Unknown

Red list index

No Change

Overview

Chlorocebus pygerythrus – (F. Cuvier, 1821)

ANIMALIA – CHORDATA – MAMMALIA – PRIMATES – CERCOPITHECIDAE – Chlorocebus – pygerythrus

Common Names: Vervet Monkey, Vervet (English), Blouaap (Afrikaans), Kgabo (Sepedi, Sesotho, Tswana), Khabo (Sesotho), Ngobiyane, Ingobiyane, Inkawu (Swati), Hacha, Nkawu, Ritoho, Ritohwe (Tsonga), Kgatla (Tswana), Thoho, Thobo (Venda), Inkawu (Xhosa, Zulu), Südafrikanische Grünmeerkatze, Vervetmeerkatze (German), Südliche Grünmeerkatze (German), Vervet Oriental (Spanish; Castilian), Vervet bleu (French)

Synonyms: Simia pygerythrus F. Cuvier, 1821; Cercopithecus pygerythrus (F. Cuvier, 1821)

Taxonomic Note:

Grubb et al. (2003) regarded this as a subspecies of C. aethiops, but it is here treated as a distinct species. Groves (2001; 2005) included this species in Chlorocebus, and lists the following subspecies: C. p. nifvoiridis [sic] probably rufoviridis; C. p. nesiotes, C. p. hilgerti, C. p. excubitor; and C. p. pygerythrus. However, only the latter subspecies exists in the assessment region. Other subspecies variously listed in Meester et al. (1986) and Skinner and Smithers (1990) are not included. The relationships of the monkeys within the vervet/grivet group and to other guenons are conflicting. Even though Grubb et al. (2003) retained vervets within the genus Cercopithecus (following the advice of the African Primate Working Group), Groves (1989, 2001, 2005) has placed them in the genus Chlorocebus. This designation has been followed by most others. Within the group Chlorocebus, there is disagreement as to whether the different geographic morphs are subspecies or species. Both Groves (2001) and Skinner and Chimimba (2005) regard them as separate species. Grubb (2006) regards Chlorocebus as a geospecies. Using 19.7 million single nucleotide variations (SNV), Warren et al. (2015) found that the differences between animals in different locations are more similar to subspecies differences in other widespread semiterrestrial primates. Recent work on mtDNA variation finds that although there are differences between local populations, these differences do not rise to the level of subspecific distinctions within the assessment region (Turner et al. 2016).

|

Red List Status |

|

LC – Least Concern, (IUCN version 3.1) |

Assessment Information

Assessors: Mercier, S.1, Thatcher, H.R.2, Pillay, K.R.3 & da Silva, J.4

Reviewer: van de Waal, E.5

Contributor: Patel, T.3

Institutions: 1University of Zurich (Switzerland), University of Lausanne (Switzerland); 2University of KwaZulu-Natal (South Africa) & University of Edinburgh (UK); 3Conservation Planning & Science Unit, Endangered Wildlife Trust, South Africa; 4South African National Biodiversity Institute, Kirstenbosch Research Centre, Cape Town, 8000, South Africa; 5 University of Lausanne (Switzerland)

Previous Assessors: Turner, T., Coetzer, W.G., Hill, R. & Patterson, L.

Previous Reviewer: Child, M.F.

Previous Contributor: Page-Nicholson, S.

Assessment Rationale

Listed as Least Concern, this species is very widespread, adaptable, and abundant, with natural habitat loss being the only significant threat. Its habitat tolerance is demonstrated by its wide distribution and adaptation to urban environments. The species thrives in diverse habitats, ranging from the high rainfall coastal dune forests of KwaZulu-Natal to the lower rainfall riverine woodlands of the Northern Cape, and in anthropogenic landscapes. Range expansions have been observed within the assessment region, and the conversion to wildlife ranching may be reclaiming habitats for this species. While the species is used locally for traditional medicine and bushmeat, this is not expected to cause a significant population decline.

Regional population effects: This species’ range is continuous throughout east Africa and there is suspected to be dispersal along the northern border of South Africa between Botswana, Zimbabwe and Mozambique through the Mapungubwe and Greater Limpopo Transfrontier areas and north-east KwaZulu-Natal. There may also be dispersal across the Namibian and South African borders, although this is yet to be demonstrated by genetic evidence.

Recommended citation: Mercier S, Thatcher HR, Pillay KR & da Silva JM. 2025. A conservation assessment of Chlorocebus pygerythrus. In Patel T, Smith C, Roxburgh L, da Silva JM & Raimondo D, editors. The Red List of Mammals of South Africa, Eswatini and Lesotho. South African National Biodiversity Institute and Endangered Wildlife Trust, South Africa.

Red List Index

Red List Index: No change

Regional Distribution and occurrence

Geographic Range

Vervet Monkeys are widespread; occurring from the Ethiopian Rift Valley, highlands east of the Rift, and southern Somalia, through the eastern lowlands of Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia (east of the Luangwa Valley), Malawi, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Botswana and all nine provinces in South Africa (Kingdon et al. 2008). Within the assessment region, they occur as far west as the George and Knysna districts of the Western Cape and they are widely distributed in a variety of habitats including the urban environment (Skinner & Chimimba 2005; Whittaker 2013, Thatcher et al. 2019a;2021). The species is also found to occur in Eswatini (Skinner & Chimimba 2005) and Lesotho (Seier 2003).

There are no obvious areas where vervets have been extirpated. They prefer drier habitats to other species in the genus, although they live happily in quite humid areas like Ballito in KwaZulu-Natal, where there is about 1010 mm of precipitation annually. They are most abundant in savannah riparian vegetation, where they can occur deep in otherwise inhospitable terrain along rivers if the riverine woodland is intact to provide fruit-bearing trees and cover (Skinner & Chimimba 2005); which explains their occurrence in the interior of the Northern Cape. They are generally absent from deserts (except riverine vegetation of river systems in deserts e.g. Orange River) and deep forest, preferring savannah, riverine woodland and coastal scrub forest areas (Stuart & Stuart 2001; Skinner & Chimimba 2005; Isbell & Jaffe 2013). They are very common along the Vaal River, and even occur on the whole length of the Molopo River. Within the North West Province, the population has expanded since the 1970s (Power 2014).

Elevation / Depth / Depth Zones

Elevation Lower Limit (in metres above sea level): 0 m

Elevation Upper Limit (in metres above sea level): 2000 m

Depth Lower Limit (in metres below sea level): (Not specified)

Depth Upper Limit (in metres below sea level): (Not specified)

Depth Zone: (Not specified)

Biogeographic Realms

Biogeographic Realm: Afrotropical

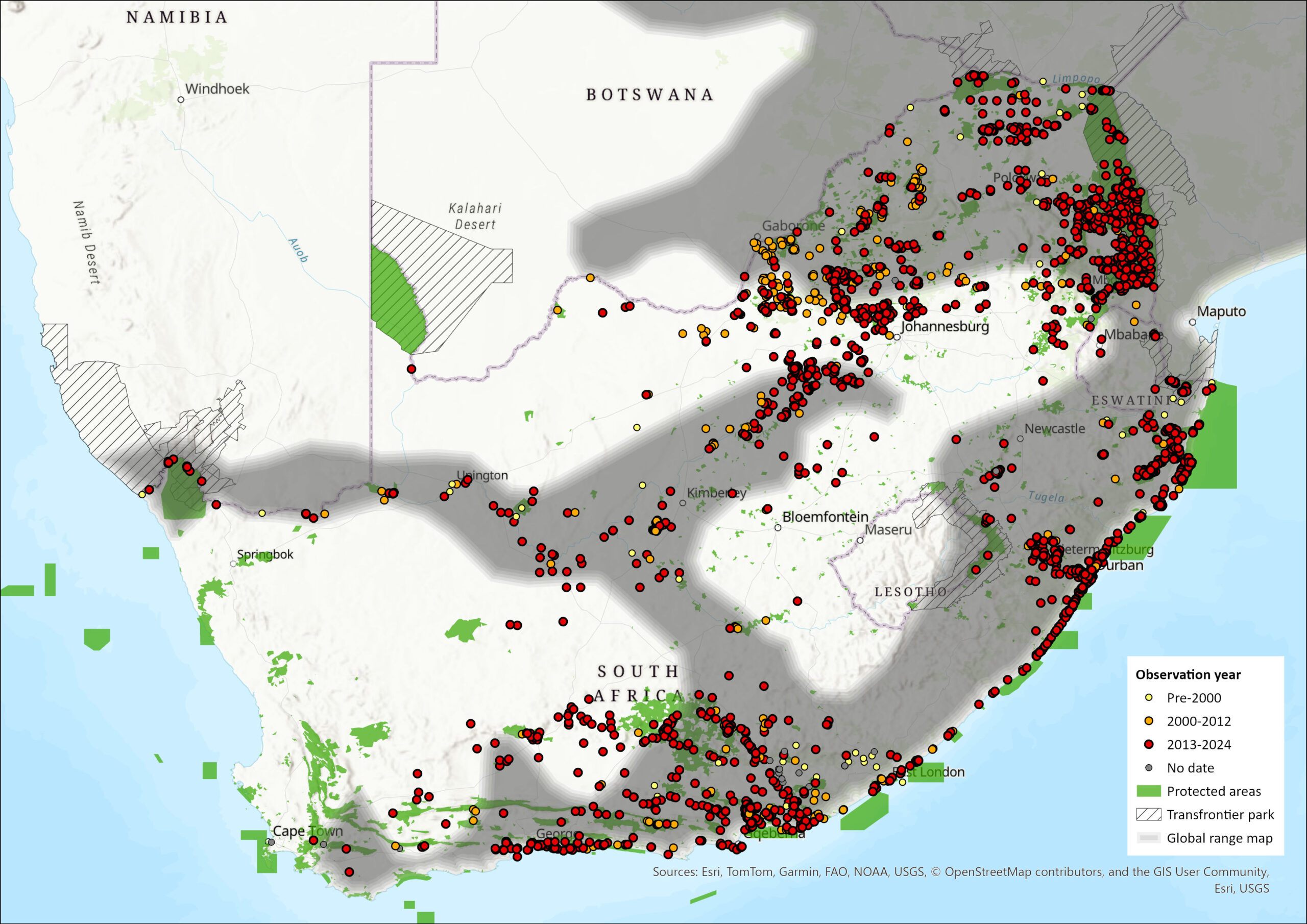

Map

Click to enlarge/view

Figure 1. Distribution records for Vervet Monkey (Chlorocebus pygerythrus) within the assessment region (South Africa, Eswatini and Lesotho). Note that distribution data is obtained from multiple sources and records have not all been individually verified.

Countries of Occurrence

|

Country |

Presence |

Origin |

Formerly Bred |

Seasonality |

|

Botswana |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

Burundi |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

Eswatini |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

Ethiopia |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

Kenya |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

Lesotho |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

Malawi |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

Mozambique |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

Namibia |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

Rwanda |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

Somalia |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

South Africa |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

Tanzania, United Republic of |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

Uganda |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

Zambia |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

Zimbabwe |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

Large Marine Ecosystems (LME) Occurrence

Large Marine Ecosystems: (Not specified)

FAO Area Occurrence

FAO Marine Areas: (Not specified)

Climate change

As climate change intensifies, Vervet Monkeys face escalating challenges, as observed in a study conducted in South Africa (Young et al. 2019). The research investigated how drought conditions impacted Vervet Monkey behaviour, physiology, and survival over 2.5 years. Findings revealed behavioural adjustments during drought periods, with monkeys spending more time resting and experiencing heightened physiological stress, indicated by increased faecal glucocorticoid metabolite levels. Mortality rates rose during food scarcity, particularly in the absence of standing water. Elevated physiological stress was linked to higher mortality probabilities. Pillay & Downs (2024) investigated pregnancy complications in wild Vervet Monkeys in the urban landscape of Durban, finding that such complications peaked in spring and were largely associated with dystocia. The study suggests that unusual climate phenomena, such as altered temperature and rainfall patterns, may impact vegetation growth and food availability, influencing breeding patterns and contributing to pregnancy complications. These results emphasise the vulnerability of Vervet Monkeys to climate-induced stressors, highlighting the urgent need for conservation efforts to mitigate these impacts.

Population information

The Vervet Monkey is widespread and often abundant. However, it is very patchily distributed over its extensive geographic range, linked to the availability of appropriate fruiting trees, sleeping trees and drinking water (Wrangham 1981; McDougall et al. 2010; Butynski and Y. de Jong, pers. comm.). It is regarded as a pest species in cultivated and urban areas in parts of its range (Estes 1991; Grobler et al. 2006; Healy & Nijman 2014; Mikula et al 2018).

The species is common throughout most provinces in South Africa. Anthropogenic development provides primates with additional food sources, crops (Lee & Priston 2005), and human-derived food (Thatcher et al. 2019b; 2020) are foraged during scarcity of natural food resources. This higher food availability may lead to range expansion, where anthropogenic activities may benefit their persistence (Pillay et al. 2023; Thatcher et al. 2019a). They live in multi- male, multi-female groups of up to 70 individuals (Stuart 2007, Dongre et al. 2024) with many unrelated males in a group. Normal troop sizes range from 14-42, with an average of 27 individuals per troop (Thatcher et al. 2019b).

Population Information

Current population trend: Unknown, although this is under debate.

Number of subpopulations: Possibly more than 1,000 (no published source for this information).

Extreme fluctuations in the number of subpopulations: (Not specified)

Continuing decline in number of subpopulations: (Not specified)

All individuals in one subpopulation: (Not specified)

Number of mature individuals in largest subpopulation: Unknown

Severely fragmented: No

Quantitative Analysis

Probability of extinction in the wild within 3 generations or 10 years, whichever is longer, maximum 100 years: (Not specified)

Probability of extinction in the wild within 5 generations or 20 years, whichever is longer, maximum 100 years: (Not specified)

Probability of extinction in the wild within 100 years: (Not specified)

Population genetics

A phylogenetic study of South African Vervet Monkeys based on mitochondrial DNA (sampled from 15 localities across their distribution), identified three well-defined genetic clusters (Coetzer et al. 2019): 1) a cluster in the savanna biome comprised of samples from northern and northeastern inland sites, as well as populations toward the northwest that fall outside the savanna areas, but are found in riverine thickets along the Orange River; 2) a central grassland cluster; and (3) a coastal thicket cluster along the southern part of the coastal belt. Rivers and mountains, as well as large geographic distances appear to be the major barriers to gene flow within this species.

While a measure of effective population size has not been calculated for each genetic cluster, diversity within each is very low, with some localities and clusters only possessing a single haplotype (Coetzer 2012; Coetzer et al. 2019). This is likely attributed to females displaying high site fidelity, resulting in low to no diversity in the mitochondrial genome. Because males are the predominant dispersers, a different outlook to the species population genetic structure and diversity might be revealed using nuclear markers.

Habitats and ecology

This species is present in a wide variety of savannah, open woodland, and forest-grassland mosaics, where it is dependent on water availability (it must drink daily) and trees for food and cover. It occurs in both high rainfall habitats such as the coastal dune forests of KwaZulu-Natal and lower rainfall areas such as the riverine woodland areas in the Northern Cape (Skinner & Chimimba 2005; Isbell & Jaffe 2013; Pillay et al. 2023). It is an extremely adaptable and versatile species able to persist in secondary and/or highly fragmented vegetation, including cultivated areas, and sometimes found living in both rural and urban environments.

Vervet Monkeys are extremely social, living in troops within which adult females form a clear linear dominance hierarchy stable over time, while males have to fight for their social ranks (Hemelrijk et al. 2020). They display high social flexibility in both their social structure (Thatcher, 2019) and social behaviour (Thatcher et al. 2019b) to anthropogenic pressures. They are largely vegetarian (wild fruits, flowers, leaves and seeds) but are also known to feed on invertebrates, birds’ eggs, birds, lizards, rodents and other vertebrate prey. In agricultural areas, they can become pests by eating beans, peas, young tobacco plants, vegetables, fruit and various grains (Skinner & Chimimba 2005). In the urban mosaic they have become opportunistic foragers, consuming human-derived food, both provisioned and opportunistic, as well as horticultural resources (Thatcher et al. 2020).

Ecosystem and cultural services: Vervet Monkeys are good vectors of seed dispersal (Butler & Johnson, 2022). Seeds are ingested as food and pass through the monkey’s digestive system intact and are excreted some distance away from where they were originally consumed. Foord et al. (1994) found that they aid succession in rehabilitating dune forests by dispersing seeds from unmined to previously mined area.

IUCN Habitats Classification Scheme

|

Habitat |

Season |

Suitability |

Major Importance? |

|

1.6. Forest -> Forest – Subtropical/Tropical Moist Lowland |

– |

Suitable |

– |

|

1.7. Forest -> Forest – Subtropical/Tropical Mangrove Vegetation Above High Tide Level |

– |

Suitable |

– |

|

1.8. Forest -> Forest – Subtropical/Tropical Swamp |

– |

Suitable |

– |

|

2.1. Savanna -> Savanna – Dry |

– |

Suitable |

– |

|

2.2. Savanna -> Savanna – Moist |

– |

Suitable |

– |

|

3.5. Shrubland -> Shrubland – Subtropical/Tropical Dry |

– |

Suitable |

– |

|

3.6. Shrubland -> Shrubland – Subtropical/Tropical Moist |

– |

Suitable |

– |

|

14.3. Artificial/Terrestrial -> Artificial/Terrestrial – Plantations |

– |

Suitable |

– |

|

14.4. Artificial/Terrestrial -> Artificial/Terrestrial – Rural Gardens |

– |

Suitable |

– |

|

14.5. Artificial/Terrestrial -> Artificial/Terrestrial – Urban Areas |

– |

Suitable |

– |

|

14.6. Artificial/Terrestrial -> Artificial/Terrestrial – Subtropical/Tropical Heavily Degraded Former Forest |

– |

Marginal |

– |

Life History

Generation Length: (Not specified)

Age at maturity: female or unspecified: (Not specified)

Age at Maturity: Male: (Not specified)

Size at Maturity (in cms): Female: (Not specified)

Size at Maturity (in cms): Male: (Not specified)

Longevity: (Not specified)

Average Reproductive Age: (Not specified)

Maximum Size (in cms): (Not specified)

Size at Birth (in cms): (Not specified)

Gestation Time: (Not specified)

Reproductive Periodicity: (Not specified)

Average Annual Fecundity or Litter Size: (Not specified)

Natural Mortality: (Not specified)

Does the species lay eggs? (Not specified)

Does the species give birth to live young: (Not specified)

Does the species exhibit parthenogenesis: (Not specified)

Does the species have a free-living larval stage? (Not specified)

Does the species require water for breeding? (Not specified)

Movement Patterns

Movement Patterns: (Not specified)

Congregatory: (Not specified)

Systems

System: Terrestrial

General Use and Trade Information

This species is used in traditional medicine where the organs and skin are harvested (Whiting et al. 2011). The meat is also used as bushmeat (Lindsey et al. 2013; Paige et al. 2014). Vervet Monkeys are also taken from the wild to be kept as pets. For example, data from the Vervet Monkey Foundation in Limpopo Province, reveals that 44% of intakes comprises ex-pets (Healy & Nijman 2014). Captive animals are still used in medical research. Harvesting is not suspected to have any negative impact on the population overall.

Wildlife ranching and the private sector have generally had a positive effect on this species as it conserved more suitable habitat and helped to connect subpopulations through game farming areas, for example in the Waterberg. In addition, some large groups have been released on land that has transitioned to wildlife ranching but the overall success and impacts of this are unknown (Wimberger et al. 2010; Guy & Curnoe 2013). A number of properties may combine game ranching with agriculture on parts of their property – where this occurs there is inevitably conflict between people and vervet monkeys.

|

Subsistence: |

Rationale: |

Local Commercial: |

Further detail including information on economic value if available: |

|

Yes |

Bushmeat/traditional medicine. |

Yes |

Biomedical research and pet trade |

National Commercial Value: Yes

International Commercial Value: No

|

End Use |

Subsistence |

National |

International |

Other (please specify) |

|

1. Food – human |

true |

– |

– |

– |

|

14. Research |

– |

true |

true |

– |

Is there harvest from captive/cultivated sources of this species? Yes

Harvest Trend Comments: Bushmeat hunting, traditional medicine and pet trade. Biomedical research.

Threats

There are no major threats although Vervet Monkeys were classed as vermin in parts of their range and they are actively persecuted (shot and hunted) by landowners in areas where they raid crops or interact with humans. For example, they are often intensively persecuted in parts of the North West and KwaZulu-Natal provinces. These negative human-wildlife interactions have been shown to lead to increased anxiety and parasite risk in the anthropogenic landscape (Thatcher et al. 2018; 2021). Large scale roads with high traffic loads in urbanised areas are also known to cause multiple deaths. For example, most of the injured monkeys taken in by the Vervet Monkey Foundation in Limpopo Province suffered injuries caused by car strikes (Healy & Nijman 2014). A study by Pillay et al. (2024), analysed admission data for Vervet Monkeys at a Durban, KZN, wildlife rehabilitation centre from 2011 to 2018. Most cases were reported by the public, with a significant increase in admissions over the years, mainly from the central district of the municipality. Sadly, a large portion of admitted Vervet Monkeys did not survive, with anthropogenic activities such as motor vehicle strikes and domestic dog attacks being the primary causes of death. They are also often reported as a problem in the many large provincial towns, and they are frequently removed (Power 2014). Vervet Monkeys are found to be a source of bushmeat in some areas. For example, Paige et al. (2014) found that Vervet Monkeys were the most frequently butchered primate for bushmeat in the study area in Uganda. They are also used as traditional medicine within the assessment region. For example, Vervet Monkeys were traded by half of the traders in the market investigated by Whiting et al. (2011).

Conservation

The Vervet Monkey is listed on Appendix II of CITES and on Class B of the African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. It is present in most protected areas within its range within the assessment region. No specific conservation interventions are necessary at present.

It is not necessary to develop captive breeding programmes. Many wildlife care programmes, such as the Centre for Rehabilitation of Wildlife (CROW), The Vervet Monkey Foundation, Riverside Rehabilitation and Education Centre, the Wild Animal Trauma Center & Haven and Bambelela have large holdings of Vervet Monkeys that have been shot, injured or orphaned in the urban, suburban environment. Reintroducing these monkeys to the wild is a significant challenge since there are few suitable localities able or willing to take them. There are also ethical issues about releasing monkeys into areas with existing populations, and releases into areas without existing populations may have problems of poor habitat suitability or high threats/mortality. Release of rehabilitated individuals into suitable areas should follow guidelines suggested by Guy and Curnoe (2013) which begins with the IUCN SSC guidelines and specifically targets them for primates. Various factors, such as habitat status, native population distribution and demographic status, genetic status of the native animals and the release stock, should be considered before reintroductions are initiated (Baker 2002). For example, while some reintroductions have been successful in KwaZulu-Natal Province, as released animals exhibited wild behaviours and established home ranges, success could be enhanced by ensuring troop composition mimics wild troops and excludes ex-pet individuals (Guy et al. 2012). Smaller reintroduced troops have also been shown to be more successful than larger troops, with only 6 of 35 individuals (17%) confirmed alive in a large troop compared with 12 of 24 (50%) in a small troop reintroduced in KwaZulu-Natal Province (Wimberger et al. 2010). Given the Vervet Monkey’s adaptability, it’s crucial to prioritize releases away from urban and residential areas to minimize human-wildlife conflicts (Pillay et al., 2023). Instead of encouraging conservancies, which often intersect with human settlements, efforts should focus on securing suitable natural habitats with minimal human disturbance. Additionally, the welfare of reintroduced monkeys must be prioritized, as captive-bred or rehabilitated individuals may struggle to adapt to the wild. Careful monitoring and post-release support are essential to ensure their well-being (Guy & Curnoe, 2013).

Recommendations for land managers and practitioners:

- Wild population management: they are regarded as problem animals and management of wild populations is necessary to reduce their risk of becoming a problem. In a number of cases, managing the human population (in terms of waste management for example) and bringing awareness on how to peacefully cohabite with Vervet Monkeys could reduce the need to manage the wildlife (Thatcher, 2019).

- Improve reintroduction techniques by radio-collaring released individuals (Guy et al. 2012).

- Form conservancies to increase the number of suitable sites for reintroduction.

Research priorities:

- Taxonomic work is required to assess the validity of proposed subspecies.

- Human-primate interface (currently being studied at the Urban Vervet Project) and ethno-primatology.

- Actual population size estimates are needed (total and regional), which can be used in conjunction with the distribution map to identify potential release sites for rehabilitated and/or damage-causing animals.

- Continued research on home range use and dietary studies within urban environments.

- The impact of direct feeding and human waste management is required to determine the effects of artificial food sources on vervet monkeys’ metabolic, physiological, and behavioural characteristics.

- Further studies into potential negative impact on indigenous birdlife.

- Population genomic work looking at nuclear variation across the species’ distribution, accompanied by measures of effective population size within each genetically distinct cluster.

Existing conservation and research projects include:

- Primate & Predator Project: Dr Russell Hill Durham University, UK.

- INKAWU Vervet Project: https://inkawuvervetproject.weebly.com/

( https://www.unil.ch/dee/en/home/menuguid/people/group-leaders/prof-erica-van-de-waal.html l).

- Urban Vervet Project: https://urbanvervetproject.weebly.com/ : Dr Sofia Forss & Dr Stephanie Mercier, University of Zurich, Switzerland & Prof Colleen Downs, Universiy of Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa

- Loskop Dam Nature Reserve: Applied Behavioural Ecology and Ecosystems Research Unit (ABEERU), University of South Africa.

- International Consortium for Vervet Monkey Research, Genetics and Life History of Vervet Monkeys, Professor Trudy Turner, UWM, Dr. Christopher Schmitt, Boston University, Dr. Nelson Freimer and Dr. Anna Jasinska, UCLA.

- Spatial ecology of vervet monkeys in urban areas of KwaZulu-Natal, Professor Colleen Downs, Dr Riddhika Kalle and PhD student Lindsay Patterson, UKZN.

- Anthropogenic influence on the behavioural ecology of Vervet Monkeys. Dr Harriet Thatcher, Professor Collen Downs and Dr Nicola Koyama, UKZN.

- Aspects of the Ecology and Persistence of Vervet Monkeys in Mosaic Urban Landscapes in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Dr Kerushka Pillay and Professor Colleen Downs, UKZN.

Encouraged citizen actions:

- Members of the public are encouraged to report sightings of free-roaming individuals outside private lands or protected areas on virtual museum platforms (for example, iNaturalist and MammalMAP) to enhance the distribution map.

Bibliography

Baker LR. 2002. IUCN/SSC Re-introduction Specialist Group: Guidelines for nonhuman primate re-introductions.

Branch B, Stuart C, Stuart T, Tarboton. 2007. Southern Africa: South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Swaziland, Lesotho, and Southern Mozambique. Double Storey Books, Cape Town, South Africa.

Butler, H. C., & Johnson, S. D. 2022. Seed dispersal by monkey spitting in Scadoxus (Amaryllidaceae): Fruit selection, dispersal distances and effects on seed germination. Austral Ecology, 47(5), 1029-1036.

Coetzer, W. G., Lorenz, J. G., Freimer, N. B., & Grobler, J. P. (2019). Population Genetic Structure of Vervet Monkeys in South Africa. Savanna Monkeys, 101–106. doi:10.1017/9781139019941.008

Dongre, P., Lanté, G., Cantat, M., Canteloup, C., & van de Waal, E. (2024). Role of immigrant males and muzzle contacts in the uptake of a novel food by wild vervet monkeys. Elife, 13, e76486.

Estes, R. 1991. The Behavior Guide to African Mammals. University of California Press, Berkely, CA.

Foord SH, van Aarde RJ, Ferreira SM. 1994. Seed dispersal by vervet monkeys in rehabilitating coastal dune forests at Richards Bay. South African Journal of Wildlife Research 24: 56-59.

Grobler P, Jacquier M, deNys H, Blair M, Whitten PL, Turner TR. 2006. Primate sanctuaries, taxonomy and survival: a case study from South Africa. Ecological and Environmental Anthropology, University of Georgia.

Groves CP. 1989. A Theory of Human and Primate Evolution. Oxford University Press, New York, USA.

Groves, C.P. 2001. Primate Taxonomy. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC, USA.

Groves, C.P. 2005. Order Primates. In: D.E. Wilson & D.M. Reeder (eds). Mammal Species of the World. A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. Third edition. Volume 1, pp. 111-184.The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

Grubb, P. 2006. Geospecies and superspecies in the African primate fauna. Primate Conservation 20: 75-78.

Grubb, P., Butynski, T.M., Oates, J.F., Bearder, S.K., Disotell, T.R., Groves, C.P. and Struhsaker, T.T. 2003. Assessment of the diversity of African primates. International Journal of Primatology 24: 1301–1357.

Guy AJ, Curnoe D. 2013. Guidelines for the Rehabilitation and Release of Vervet Monkeys. Primate Conservation 27: 55-63.

Guy AJ, Stone OM, Curnoe D. 2012. The release of a troop of rehabilitated vervet monkeys (Chlorocebus aethiops) in KwaZuluNatal, South Africa: outcomes and assessment. Folia Primatologica 82: 308-320.

Healy A, Nijman V. 2014. Pets and pests: vervet monkey intake at a specialist South African rehabilitation centre. Animal Welfare 23: 353-360.

Hemelrijk, C. K., Wubs, M., Gort, G., Botting, J., & Van de Waal, E. (2020). Dynamics of intersexual dominance and adult sex-ratio in wild vervet monkeys. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 839.

Isbell, L.A. and Enstam Jaffe, K.L. 2013. Chlorocebus pygerythrus Vervet Monkey. In: T.M. Butynski, J. Kingdon and J. Kalina (eds), Mammals of Africa. Volume II: Primates, pp. 277–283. Bloomsbury Pub-lishing, London.

Kingdon J, Gippoliti S, Butynski TM, De Jong Y. 2008. Chlorocebus pygerythrus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T136271A4267738. Available at: http:// dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T136271A4267738.en.

Lee PC, Priston NE. 2005. Human attitudes to primates: perceptions of pests, conflict and consequences for primate conservation. In: Paterson JD, Wallis J (ed.), Commensalism and Conflict: The Primate-Human Inteface, pp. 1-23. American Society of Primatologists, Norman.

Lindsey, P.A., Balme, G., Becker, M., Begg, C., Bento, C., Bocchino, C., Dickman, A., Diggle, R.W., Eves, H., Henschel, P., Lewis, D., Marnewick, K., Mattheus, J., McNutt, J.W., McRobb, R., Midlane, N., Milanzi, J., Morley, R., Murphree, M., Opyene, V., Phadima, J., Purchase, G., Rentsch, D., Roche, C., Shaw, J., Van der Westhuizen, H.,Van Vliet, N. and Zisadza-Gandiwa, P. 2013. The bushmeat trade in African savannas: Impacts, drivers, and possible solutions. Biological Conservation 160: 80-96.

McDougall P, Forshaw N, Barrett L, Henzi SP. 2010. Leaving home: responses to water depletion by vervet monkeys. Journal of Arid Environments 74: 924-927.

Meester, J.A.J., Rautenbach, I.L., Dippenaar, N.J. and Baker, C.M. 1986. Classification of Southern African Mammals. Monograph number 5. Transvaal Museum, Pretoria, South Africa.

Mikula, P., Šaffa, G., Nelson, E., & Tryjanowski, P. (2018). Risk perception of vervet monkeys Chlorocebus pygerythrus to humans in urban and rural environments. Behavioural processes, 147, 21-27.

Paige SB, Frost SD, Gibson MA, Jones JH, Shankar A, Switzer WM, Ting N, Goldberg TL. 2014. Beyond bushmeat: animal contact, injury, and zoonotic disease risk in Western Uganda. EcoHealth 11: 534-543.

Pillay, K. R. (2022). Aspects of the Ecology and Persistence of Vervet Monkeys in Mosaic Urban Landscapes in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa (Doctoral dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg).

Pillay, K. R., Streicher, J. P., & Downs, C. T. (2023). Home range and habitat use of vervet monkeys in the urban forest mosaic landscape of Durban, eThekwini Municipality, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Urban Ecosystems, 26(6), 1769-1782.

Pillay, K. R., & Downs, C. T. (2024). Pregnancy complications in wild vervet monkeys in an urban mosaic landscape. African Journal of Ecology, 62(1), e13251.

Pillay KR, Streicher JP and Downs CT. (2024). Trends in vervet monkey admissions to a wildlife rehabilitation centre: A reflection of human-wildlife conflict in an urban-forest mosaic landscape. Mammalian Biology 104, 707-723. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42991-024-00447-x

Power, R.J. 2014. The distribution and status of mammals in the North West Province. Department of Economic Development, Environment, Conservation & Tourism, North West Provincial Government, Mahikeng.

Seier J. 2003. Supply and use of nonhuman primates in biomedical research: A South African perspective. National Research Council: 16-19.

Skinner, J.D. and Chimimba, C.T. (eds). 2005. The Mammals of the Southern African Subregion. Cambridge University Press, United Kingdom, Cambridge.

Skinner, J.D. and Smithers, R.H.N. 1990. The Mammals of the Southern African Subregion, second edition University of Pretoria, Pretoria. South Africa.

Stuart C, Stuart T. 2001. Field Guide to Mammals of Southern Africa. Struik Publishers, Cape Town, South Africa.

Thatcher, H. R. (2019). Anthropogenic influences on the behavioural ecology of urban vervet monkeys. Liverpool John Moores University (United Kingdom).

Thatcher, H.R., Downs, C.T. & Koyama, N.F. (2020). Understanding foraging flexibility in urban vervet monkeys, Chlorocebus pygerythrus, for the benefit of human-wildlife coexistence. Urban Ecosystems, 23(6):1349-1357.

Thatcher, H.R., Downs, C.T. & Koyama, N.F. (2019a). Positive and negative interactions with humans concurrently affect vervet monkey (Chlorocebus pygerythrus) ranging behavior. International Journal of Primatology, 40:496-510.

Thatcher, H.R., Downs, C.T. & Koyama, N.F. (2019b). Anthropogenic influences on the time budgets of urban vervet monkeys. Landscape and Urban Planning, 181:38-44.

Thatcher, H. R., Downs, C. T., & Koyama, N. F. (2021). The costs of urban living: human–wildlife interactions increase parasite risk and self-directed behaviour in urban vervet monkeys. Journal of Urban Ecology, 7(1), juab031.

Turner TR, Coetzer WG, Schmitt CA, Lorenz JG, Freimer NB, Grobler JP. 2016. Localized population divergence of vervet monkeys (Chlorocebus spp.) in South Africa: Evidence from mtDNA. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 159: 17-30.

Warren WC et al. 2015. The genome of the vervet (Chlorocebus aethiops sabaeus). Genome Research 25: 1921–1933.

Whiting, M.J., Williams, V.L. and Hibbitts, T.J. 2011. Animals traded for traditional medicine at the Faraday market in South Africa: species diversity and conservation implications. Journal of Zoology 284: 84-96.

Whittaker D. 2013. Chlorocebus: species accounts. Pages 672– 675 in Mittermeier RA, Rylands AB, Wilson DE, editors. Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Volume 3: Primates. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, Spain.

Wimberger K, Downs CT, Perrin MR. 2010. Postrelease success of two rehabilitated vervet monkey (Chloroceus aethiops) troops in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Folia Primatologica 81: 96-108.

Wrangham RW. 1981. Drinking competition in vervet monkeys. Animal Behaviour 29: 904-910.

Young, C., Bonnell, T.R., Brown, L.R., Dostie, M.J., Ganswindt, A., Kienzle, S., McFarland, R., Henzi, S.P. and Barrett, L., 2019. Climate induced stress and mortality in vervet monkeys. Royal Society Open Science, 6(11), p.191078.