Southern Lesser Galago

Galago moholi

2025 Red list status

Least Concern

Regional Population Trend

Stable

red list index

No Change

Overview

Galago moholi – A. Smith, 1836

ANIMALIA – CHORDATA – MAMMALIA – PRIMATES – GALAGIDAE – Galago – moholi

Common Names:) Southern Lesser Galago, South African Galago, South African Lesser Galago, Lesser Galago, Night Ape, Bushbaby African Lesser Bushbaby (English), Nagapie (Afrikaans), Impukunyoni (Ndebele), Maselale-ntlwë (Sesotho), Mhimbi (Tsonga), Mogwele (Tswana), Tshimondi (Venda)

Synonyms: Galago moholi ssp. bradfieldi Roberts, 1931; Galago moholi ssp. moholi A. Smith, 1836; australis, conspicillatus, intontoi, mossambicus, tumbolensis

Taxonomic Note:

Galago moholi was recognised as a new species by Sir Andrew Smith during his epic journey into the South African interior between 1834 and 1836. Schwarz (1931) and Hill (1953) downgraded it to a subspecies of the Senegal Lesser Bushbaby (Galago senegalensis), because of morphological similarities, but it was resurrected as a distinct species on the basis of consistent differences in the structure of its advertisement calls (Zimmermann et al. 1988). Currently, we recognise it as one species with two subspecies (Meester et al. 1986; Grubb et al. 2003): Galago m. moholi in the eastern part of the range, and G. m. bradfieldi (Roberts 1931) in the northern reaches. Galago moholi is slightly smaller in body size than the northern species, and has much longer ears. The species share a chromosome number of 2n = 38. Galago moholi can be distinguished from Galagoides granti by its paler pelage colouration: while G. granti has a dark brown body and tail, G. moholi is predominantly pale grey on the dorsum, head and outer surfaces of the limbs. The back and rump may be washed with russet brown, while the tail is generally covered in a mix of brown and grey hairs. The face is suffused with white, and the pale nose stripe has diffuse margins. The limbs are washed with yellow, and the ventral surface is white.

|

Red List Status |

|

LC – Least Concern, (IUCN version 3.1) |

Assessment Information

Assessors: Patel, T1. & da Silva, J.2

Reviewer: Scheun, J.3

Contributors: Bearder, S. & McDonald, K.

Institutions: 1Endangered Wildlife Trust, 2South African National Biodiversity Institute, 3Department of Nature Conservation, Tshwane University of Technology

Previous Assessors & Reviewers: Masters, J., Génin, F. & Bearder, S.

Previous Contributors: Page, S. & Child, M.F.

Assessment Rationale

Listed as Least Concern, as the species is widespread in Acacia woodland habitats. No major threats are assumed as the species occurs in many protected areas throughout its range. As in the case of the Thick-tailed Greater Galago (Otolemur crassicaudatus), northern South Africa marks the southernmost limit of the species’ range, but the Lesser Galago habitat is more continuous and less fragmented than that of its larger relative. Although the species is used opportunistically as bushmeat, traditional medicine and in the pet trade, these depredations are not expected to cause widespread population decline. Caution should be exercised, however, as few population size or density estimates have been conducted, and its cryptic nocturnal habits make it difficult to assess both its presence and abundance. Monitoring of populations is recommended.

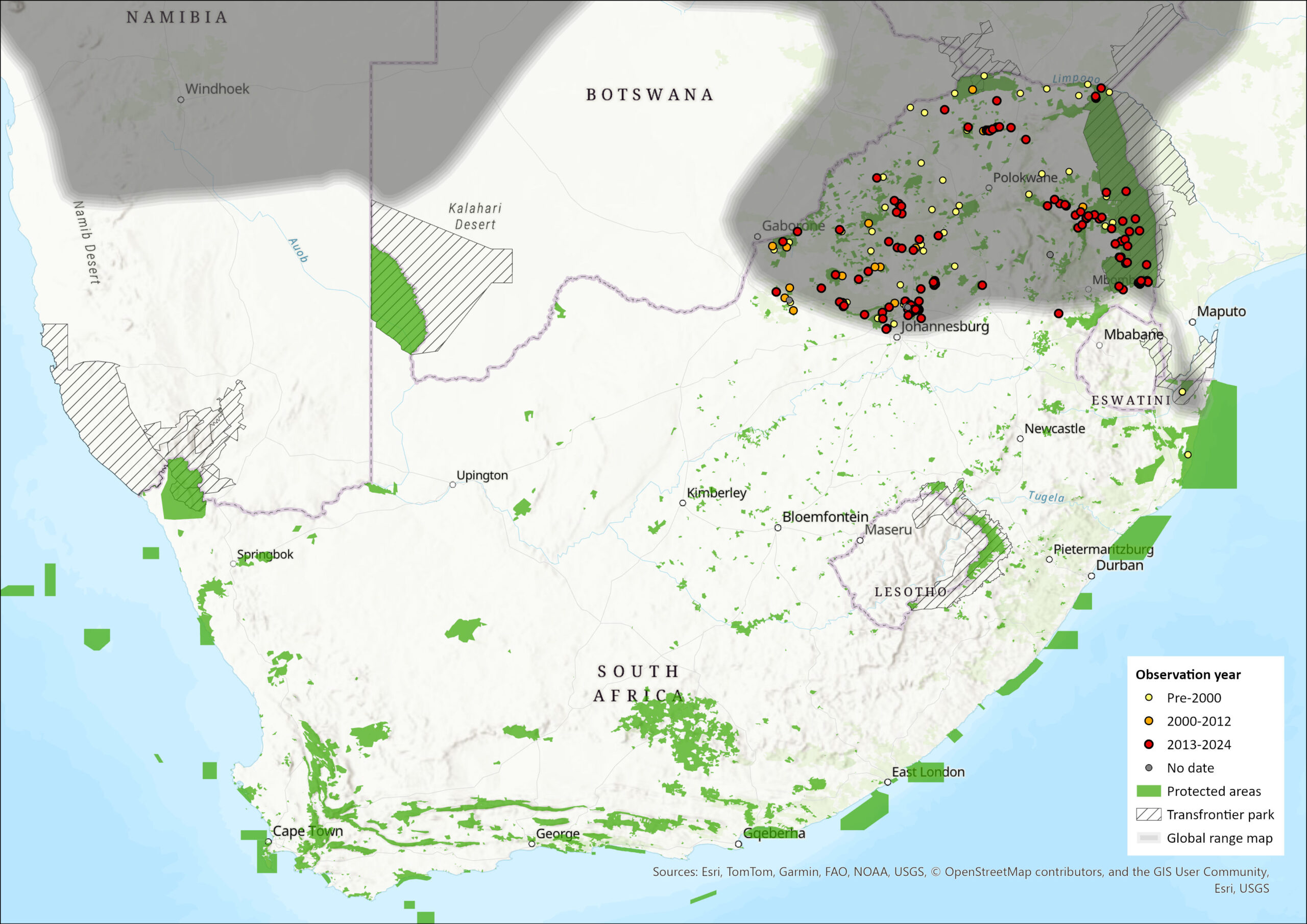

Regional population effects: This species’ range is relatively continuous throughout southern Africa to southern Tanzania, where the northern boundary of their distribution is not well defined. Dispersal is suspected to occur along the northern border of South Africa into Botswana, Zimbabwe and Mozambique through the Greater Mapungubwe and Great Limpopo transfrontier areas. The distribution of the species in northeastern KwaZulu-Natal needs to be re-examined in light of the identification of the similar-sized Galagoides granti in the region.

Recommended citation: Patel T & da Silva JM. 2025. A conservation assessment of Galago moholi. In Patel T, Smith C, Roxburgh L, da Silva JM & Raimondo D, editors. The Red List of Mammals of South Africa, Eswatini and Lesotho. South African National Biodiversity Institute and Endangered Wildlife Trust, South Africa.

Reasons for Change

Reason(s) for Change in Red List Category from the Previous Assessment: No change

Red List Index

Red List Index: No change

Regional Distribution and occurrence

Geographic Range

The Southern Lesser Galago is widely distributed within the southern African region, ranging from northern Namibia and Angola, through southeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, western Zambia, Zimbabwe, eastern and northern Botswana, eastern Mozambique, and the northern and northeastern parts of South Africa, and Eswatini (Pullen & Bearder 2013). The northern limits of its distribution range are not well defined, and its potential presence in Rwanda and Burundi needs confirmation. Within the assessment region, the species occurs in the bushveld and woodland areas of Gauteng, Mpumalanga, Limpopo and North West provinces, and may frequent gardens in these areas. Unlike many other woodland species, there is no evidence of a range shift. Although Kyle (1996) reported the species as present in northern KwaZulu-Natal, it is possible that the true identity of the sighting was Galagoides granti, which is of a similar size (Génin et al. 2016). Further field surveys are needed to confirm this.

The subspecies G. m. moholi occupies the eastern part of the distribution, including the species’ type locality on the banks of the Limpopo/Marikwa Rivers, and areas of savannah woodland in Limpopo, Mpumalanga and North West provinces, as well as northern Gauteng. In Pretoria and environs there have been several reports of groups living close to human dwellings, and even sightings in the Acacia thornveld that surrounds the Union Buildings. The subspecies G. m. bradfieldi ranges from northern Namibia into Angola, northwards and eastwards in Botswana to the Makgadikgadi Pan, moving into semi-arid regions along dry watercourses that support Acacia woodland; also found in western Zambia (Skinner & Chimimba 2005).

Elevation / Depth / Depth Zones

Elevation Lower Limit (in metres above sea level): (Not specified)

Elevation Upper Limit (in metres above sea level): (Not specified)

Depth Lower Limit (in metres below sea level): (Not specified)

Depth Upper Limit (in metres below sea level): (Not specified)

Depth Zone: (Not specified)

Biogeographic Realms

Biogeographic Realm: Afrotropical

Map

Figure 1. Distribution records for Southern Lesser Galago (Galago moholi) within the assessment region (South Africa, Eswatini and Lesotho). Note that distribution data is obtained from multiple sources and records have not all been individually verified.

Countries of Occurrence

|

Country |

Presence |

Origin |

Formerly Bred |

Seasonality |

|

Angola |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

Botswana |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

Burundi |

Presence Uncertain |

– |

– |

– |

|

Congo, The Democratic Republic of the |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

Eswatini |

Possibly extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

Lesotho |

Absent |

– |

|

|

|

Malawi |

Presence uncertain |

– |

– |

– |

|

Mozambique |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

Namibia |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

Rwanda |

Presence Uncertain |

– |

– |

– |

|

South Africa |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

Tanzania, United Republic of |

Presence uncertain |

– |

– |

– |

|

Zambia |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

Zimbabwe |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

Large Marine Ecosystems (LME) Occurrence

Large Marine Ecosystems: (Not specified)

FAO Area Occurrence

FAO Marine Areas: (Not specified)

Climate change

Primates face several threats, and this exacerbates their risk of local or global extinction due to environmental change (Pacifici et al. 2017). A review conducted on the possible impact of climate change and human induced environmental change on the feeding ecology, genetics, thermal biology, and reproduction of G. moholi showed that this species may be able to adapt to changing conditions due to its nocturnal lifestyle and high levels of behavioural and physiological plasticity (Scheun & Nowack, 2023). For example, G. moholi uses selective torpor as an energy– and water-saving adaptation in order to increase body temperature and maintain homeostasis (Scheun & Nowack, 2023). Furthermore, the study revealed that this species adapts its diet by exploiting a diverse range of food sources during periods when natural supplies are diminished due to seasonal change or habitat alterations (Scheun et al. 2015).

Population information

This is a common and widespread species, found in highest densities associated with Vachellia karroo. Development and land conversion for agriculture has reduced habitat in the past. However, G. moholi is a robust species found throughout the woodland savannah biome. Furthermore, wildlife ranching is assumed to generally improve habitat conditions for this species or conserve land that would otherwise be cleared for livestock (however, further research is needed to confirm this). No published data are available for longevity in the wild but captive individuals may live for 13 years. The age of reproductive maturity in females (first oestrus) is approximately nine months, although successful reproduction may not occur until the second oestrus period 5–6 months later. An intensive study of radio-tagged individuals in a 1×1 km area revealed 31 individuals / km2 (Bearder & Martin 1979). Other density estimates (reviewed in Pullen & Bearder 2013) are 13.5 animals / km2 in northeastern South Africa and > 50 animals / km2 in Balovale, Zambia; this suggests that there are likely to be over 10,000 mature individuals given their wide distribution and occurrence in both protected areas and transformed areas (such as gardens). Bearder and Martin (1979) found the average home range size to be around 12 ha.

Population Information

Current population trend: Stable

Continuing decline in mature individuals: Not suspected, although opportunistic poaching may occur and cause localised declines.

Number of mature individuals in population: Unknown

Number of mature individuals in largest subpopulation: Unknown

Number of subpopulations: Unknown

Severely fragmented: No

Quantitative Analysis

Probability of extinction in the wild within 3 generations or 10 years, whichever is longer, maximum 100 years: (Not specified)

Probability of extinction in the wild within 5 generations or 20 years, whichever is longer, maximum 100 years: (Not specified)

Probability of extinction in the wild within 100 years: (Not specified)

Population genetics

While a phylogenetic study on Larisform primates, including Galago moholi, has been conducted (Pozzi et al. 2015), no population genetic study on this species has been undertaken. Accordingly, the genetic structure (number of genetically distinct populations) and diversity within this species cannot be quantified. However, given that females show high site fidelity, with males dispersing out of their home ranges, it is important that future population genetic studies utilise fine scale nuclear markers to uncover the full picture of the current genetic structure and diversity.

Habitats and ecology

The Lesser Galagos (Galago) are the most recent galagid genus to have diversified, and at least three species have evolved to occupy relatively open habitats within the last 1 million years. Galago is distributed across the bushveld and woodland of sub-Saharan Africa, where it encounters diverse habitat conditions, although the different species have remained morphologically very similar. It is possible that there are more cryptic species awaiting discovery within the group, north of the assessment region. Lesser Galagos can survive in relatively arid areas and are independent of water, satisfying their fluid requirements from their food. G. moholi is found in all strata in savannah woodland from southern Tanzania southwards, and is particularly associated with Acacia spp. in South Africa which provide a source of gum. The species also occurs in miombo and mopane woodland, riverine gallery forest and at the edges of wooded areas. It is able to live in association with human settlements. Found from sea level to 1,500 m asl (Soutpansberg Mountains).

Acacia and mopane may contain tree holes, and mopane often have hollowed-out trunks, which serve both as resting and breeding sites. Females also build leafy nests during the wet season, or they simply sleep hidden among branches. At dawn the animals may form sleeping groups of two to seven individuals, who will huddle together in a furry ball to sleep through the daylight hours, but the animals disperse at dusk to forage alone or, occasionally, in pairs. Female offspring may remain with the mother on maturity, sharing her home range and raising offspring together with her, while male offspring disperse out of the maternal range at the age of about nine months. After moving, young males are non-territorial and range widely over the territories of older males and females. The territory of a ‘resident’ or established male is smaller, overlapping those of one to three adult females.

Adult males are slightly larger than adult females when mature. Females give birth to 1–3 offspring during two birth seasons, in October/early November and again in late January/early February (Doyle et al. 1971; Scheun et al. 2016; Scheun et al. 2017). In a mother-daughter partnership, the mother is usually the first to breed. After birth, the females experience a post-partum oestrus, giving them the chance to breed twice during a single summer/rainy season. This is a reproductive system geared to a highly unpredictable environment with high mortality rates for offspring and juveniles, indicating that Lesser Galagos – though widely distributed and relatively flexible ecologically – live in a challenging and often lethal environment. Whether the high frequency of multiple births reported for this species (approximately 60%) is consistent throughout the species’ range, or more prevalent in the most unpredictable parts (such as in South Africa and Namibia), has not been systematically investigated.

G. moholi communicate chiefly using odour and sound, although they have excellent night vision and appear to recognise one another from a distance. Both males and females have sternal apocrine glands that secrete polysaccharides, and the animals can be seen rubbing their chests or mouths on sticks or protuberances in the areas they frequent most. Lesser Galagos also practice “urine-washing”, coating the hands and feet with urine which is transferred to the fur of social group members during bouts of reciprocal grooming. Urine-washing dampens the hands and feet and may improve grip. It is often associated with fear or insecurity, and the animals will perform this stereotyped behaviour whenever they enter a new space that is not already saturated with their own odour. G. moholi has an extensive vocal repertoire comprising up to 25 different calls that are emitted in a variety of contexts: alarm calls, threats, vocal advertisement by residents of a home range, gathering calls for group members prior to entry into the sleeping site, courtship calls by males to entice potentially receptive females, infant distress calls, and soothing contact calls by the mother to distressed infants. The advertisement call is peculiar to and diagnostic of the species.

Ecosystem and cultural services: Lesser Galagos are primarily insectivorous and gummivorous. They appear to have co-evolved with gum-producing trees and they help to control insect numbers (Bearder & Martin 1980). Moths are a special delicacy, many species of which are agricultural pests. The animals’ penchant for nectar also suggests a role in pollination of indigenous plant species.

Recent observations have confirmed that, in some regions, Lesser Galagos will eat fruits and small vertebrates (lizards and geckos), although this seems to be a locally acquired habit that is never seen in other areas (Nowack et al. 2012; 2013).

IUCN Habitats Classification Scheme

|

Habitat |

Season |

Suitability |

Major Importance? |

|

2.1. Savanna -> Savanna – Dry |

– |

Suitable |

– |

Life History

Generation Length: (Not specified)

Age at maturity: female or unspecified: (Not specified)

Age at Maturity: Male: (Not specified)

Size at Maturity (in cms): Female: (Not specified)

Size at Maturity (in cms): Male: (Not specified)

Longevity: (Not specified)

Average Reproductive Age: (Not specified)

Maximum Size (in cms): (Not specified)

Size at Birth (in cms): (Not specified)

Gestation Time: (Not specified)

Reproductive Periodicity: (Not specified)

Average Annual Fecundity or Litter Size: (Not specified)

Natural Mortality: (Not specified)

Does the species lay eggs? (Not specified)

Does the species give birth to live young: (Not specified)

Does the species exhibit parthenogenesis: (Not specified)

Does the species have a free-living larval stage? (Not specified)

Does the species require water for breeding? (Not specified)

Movement Patterns

Movement Patterns: (Not specified)

Congregatory: (Not specified)

Systems

System: Terrestrial

General Use and Trade Information

Lesser Galagos are consumed as bushmeat, as their sleeping habits (the use of tree holes or leaf platforms by one to several animals during the daytime) make them easy prey. They are seen in muthi markets (Whiting et al. 2011), where their organs are on sale for use in traditional medicine. Their appealing faces – with their big eyes and big ears – make them desirable as pets, and they are trapped illegally for the pet trade. These practices may be causing local population declines but are unlikely to have an effect over the species’ wide range. The private sector may have generally had a positive effect on this species as it has conserved more habitat suitable for Lesser Galagos (for example, by protecting areas of Acacia thornveld that might otherwise be harvested for firewood) and thus may have helped to connect subpopulations through game farming areas, for example in the Waterberg. However, this remains to be investigated.

|

Subsistence: |

Rationale: |

Local Commercial: |

Further detail including information on economic value if available: |

|

Yes |

Poaching for bush meat. |

Yes |

Illegal harvest for the pet trade and for traditional medicine. |

National Commercial Value: (Not specified)

International Commercial Value: (Not specified)

|

End Use |

Subsistence |

National |

International |

Other (please specify) |

|

1. Food – human |

true |

– |

– |

– |

|

3. Medicine – human & veterinary |

true |

– |

– |

– |

Is there harvest from captive/cultivated sources of this species? (Not specified)

Harvest Trend Comments: (Not specified)

Threats

There are no major anthropogenic threats. Bearder et al. (2008) suggests the range of the species is expanding in some areas, such as in Gauteng where it was not previously known. However, potential range expansion needs further research. Arable farming is giving way to game ranching and regeneration of natural vegetation in some areas. However, expansion of human settlements is suspected to have fragmented the Southern Lesser Galago’s habitat, which may result in inbreeding amongst isolated subpopulations. This is of primary concern in Gauteng Province. The species is illegally harvested for the pet trade, and captured individuals seldom survive without expert care. Lesser Galagos are seen in muthi markets, indicating use in traditional medicine. Poaching for bushmeat is facilitated by the animals’ somnolence and use of communal nests during the day, when several animals can be trapped at once by simply blocking the entrance. This widespread practice may be causing local declines and, worryingly, may be increasing around protected area edges (sensu Wittemyer et al. 2008).

Overall, galagos are relative generalists and can cope with habitat changes by diet shifting, but their breeding strategy also indicates habitat unpredictability and a rapid reproductive rate to cover high infant and juvenile mortality. Loss of habitat by tree-felling/harvesting will significantly affect local population viability. The species is particularly dependent upon Acacia gum nutrition, especially in winter when fewer insects are available. Thus, replacement of natural woodlands by commercial plantations will negatively impact this species (Armstrong & van Hensbergen 1996; Munyati & Kabanda 2009).

Lesser galagos are well adapted to weather extremes. In some parts of their range, they grow a dense underfur before the onset of winter, when temperatures can fall to -6.5 C, and they become inactive and enter a phase of torpor when food sources become frozen (Nowack et al. 2013).

Habitat trend: Continuing decline. Between 2000 and 2013 there was an expansion in rural settlements of between 6.5–38.7% and an expansion in urban settlements of between 8.1–14.9% in North-West, Limpopo, Mpumalanga and Gauteng provinces (GeoTerraImage 2015). In the Soutpansberg, Limpopo Province, pine and eucalyptus plantations and residential housing expansion reduced woodland cover by 20% over a 16 year period between 1990 and 2006 (Munyati & Kabanda 2009).

Conservation

This species occurs in a number of protected areas throughout its range within the assessment region, including Kruger National Park. Galagos adapt well to captivity and breed very successfully under expert care, and such facilities can be used to reintroduce this species into conservancies and other protected areas. Reintroductions are not recommended at this stage, however, as the real extent of the species’ distribution, and the degree of range fragmentation, have yet to be established. Conservationists should continue to enforce protected area rules and prevent the illegal harvesting of firewood. Landowners should continue to form conservancies to protect woodland habitat.

- moholi has been observed to be thriving in a wildlife estate in Hoedspruit, Limpopo, readily becoming habituated to its human neighbours, using roof cavities (thatch and other) as roost sites and emerging at night to forage in the bush which, by the nature of these estates, surrounds the houses. Supplementary feeding by residents also occurs and this kind of human settlement is beneficial to the local galagos (McDonald, pers. Comms, 2024). However, additional research is needed to determine what the effect of long-term consumption of anthropogenic food sources will be on the species. In addition, urbanisation brings with it various novel threats, such as novel pathogens, predators and linear infrastructure. Research is needed on how these might affect reproduction and survival rates of the species (Scheun & Nowack, 2023).

Recommendations for land managers and practitioners:

- Captive breeding and reintroduction are not recommended at this stage, as no data exist concerning the genetic structure of this species within South Africa. Its previous confusion with Galagoides granti means that its geographic distribution and habitat requirements have yet to be established. We currently have a situation where one of our most common species has to be re-evaluated.

- The most proactive conservation measures at this stage would be to form conservancies for savannah-woodland habitat areas, and to prevent the uncontrolled removal of firewood.

Research priorities:

- Estimate the true extent of the G. moholi distribution and habitat requirements in light of the discovery of Galagoides granti within the borders of South Africa. A systematic census linking species and habitat types is essential for future conservation planning.

- Assess population genetics to determine the degree of population connectivity and diversity (and possible genetic isolation of populations and inbreeding). This is fundamental to understanding the health and persistence of this species.

- Long-term research on the effect of climate change on the survival likelihood of this species and other galago species.

- Research on the impact of urbanisation on the species.

Encouraged citizen actions:

- The discovery of Galagoides granti in northern KwaZulu-Natal places in doubt the opinion that G. moholi occurs in this province. The most pressing need for an assessment of this species’ population size and density estimates is a systematic census of KwaZulu-Natal Province reserves and private lands to document the true extent of its geographic range. Land-owners and ecotourists can assist by attempting to identify any Lesser Galagos that occur either on their properties or within protected areas and report these sightings on virtual museum platforms (for example, iNaturalist and MammalMAP) to assist in the re-assessment of the relative distributions of G. moholi and Galagoides granti.

- Woodland habitats are more fragile than they may at first appear, and Acacia trees in particular are sought after for firewood. Lesser Galago populations would benefit from the creation of conservancies to protect thornveld areas and prevent their over-exploitation.

Bibliography

Avery G. 1990. Avian fauna, palaeoenvironments and palaeoecology in the Late Quaternary of the Western and Southern Cape, South Africa. University of Cape Town.

Armstrong, A.J. and van Hensbergen, H.J. 1996. Impacts of afforestation with pines on assemblages of native biota in South Africa. South African Forestry Journal 175: 35-42.

Bearder S, Butynski TM, Hoffmann M. 2008. Galago moholi. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T8788A12932349.

Bearder SK, Martin D. 1979. The social organisation of a nocturnal primate revealed by radio tracking. Pages 633–648 in Amlaner CJ, MacDonald JDW, editors. A Handbook on Biotelemetry and Radio Tracking. Pergamon Press, Oxford, UK.

Bearder SK, Martin RD. 1980. Acacia gum and its use by bushbabies, Galago senegalensis (Primates: Lorisidae). International Journal of Primatology 1: 103–128.

Bearder SK. 1987. Lorises, bushbabies, and tarsiers: diverse societies in solitary foragers. Pages 11–24 in Smuts BB, Cheney DL, Seyfarth RM, Wrangham RW, Struhsaker TT, editors. Primate Societies. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, USA.

Doyle GA, Andersson A, Bearder SK. 1971. Reproduction in the lesser bushbaby (Galago senegalensis moholi) under seminatural conditions. Folia Primatologica 14: 15–22.

GeoTerraImage. 2015. 1990-2013/14 South African National Land-Cover Change. DEA/CARDNO SCPF002: Implementation of Land-Use Maps for South Africa. Project Specific Data Report.

Grubb, P., Butynski, T.M., Oates, J.F., Bearder, S.K., Disotell, T.R., Groves, C.P. and Struhsaker, T.T. 2003. Assessment of the diversity of African primates. International Journal of Primatology 24: 1301–1357.

Génin F, Yokwana A, Kom N, Couette S, Dieuleveut T, Nash SD, Masters JC. 2016. A new galago species for South Africa (Primates: Strepsirhini: Galagidae). African Zoology 51: 135–143.

Hill, W.C.O. 1953. Primates: Comparative Anatomy and Taxonomy. I – Strepsirhini. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, UK.

Kyle R. 1996. Sight records of Galago moholi, the lesser bushbaby, in KwaZulu-Natal. Lammergeyer 44: 39–40.

Meester, J.A.J., Rautenbach, I.L., Dippenaar, N.J. and Baker, C.M. 1986. Classification of Southern African Mammals. Monograph number 5. Transvaal Museum , Pretoria, South Africa.

Munyati C, Kabanda TA. 2009. Using multitemporal Landsat TM imagery to establish land use pressure induced trends in forest and woodland cover in sections of the Soutpansberg Mountains of Venda region, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Regional Environmental Change 9: 41–56.

Nowack, J., Wippich, M., Mzilikazi, N. et al. 2012. Surviving the Cold, Dry Period in Africa: Behavioral Adjustments as an Alternative to Heterothermy in the African Lesser Bushbaby (Galago moholi). Int J Primatol 34, 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-012-9646-8

Nowack, J., Mzilikazi, N. & Dausmann, K.H. 2013. Torpor as an emergency solution in Galago moholi: heterothermy is triggered by different constraints. J Comp Physiol B 183, 547–556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00360-012-0725-0

Pacifci, M., Visconti, P., Butchart, S. H. M., Watson, J. E. M., Cassola, F. M., & Rondinini, C. 2017. Species’ traits influenced their response to recent climate change. Nature Climate Change, 7(3), 205–208.

Pullen S, Bearder SK. 2013. Galago mohali Southern Lesser Galago (South African Lesser Galago). Pages 430–433 in Butynski TM, Kingdon J, Kalina J, editors. Mammals of Africa. Volume II: Primates. Bloomsbury Publishing, London, UK.

Roberts A. 1931. New forms of South African mammals. Annals of the Transvaal Museum 14: 221–236.

Scheun, J., Nowack, J., Bennett, N.C. & Ganswindt, A., 2016. Female reproductive activity and its endocrine correlates in the African lesser bushbaby, Galago moholi. Journal of Comparative Physiology B, 186(2), pp.255-264.

Scheun, J., Bennett, N.C., Nowack, J. & Ganswindt, A., 2017. Reproductive behaviour, testis size and faecal androgen metabolite concentrations in the African lesser bushbaby. Journal of Zoology, 301(4), pp.263-270.

Scheun, J.& Nowack, J. 2023. Looking Ahead: Predicting the Possible Ecological and Physiological Response of Galago Moholi to Environmental Change. International Journal of Primatology, 45: 1448-1471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-023-00373-8

Schwarz E. 1931. On the African long-tailed Lemurs or Galagos. Journal of Natural History 7: 41–66.

Skinner J.D. and Chimimba C.T. 2005. The Mammals of the Southern African Subregion. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Whiting, M.J., Williams, V.L. and Hibbitts, T.J. 2011. Animals traded for traditional medicine at the Faraday market in South Africa: species diversity and conservation implications. Journal of Zoology 284: 84-96.

Wittemyer, G., Elsen, P., Bean, W.T., Burton, A.C.O. and Brashares, J.S. 2008. Accelerated human population growth at protected area edges. Science 321: 123-126.

Zimmermann E, Bearder SK, Doyle GA, Andersson AB. 1988. Variations in vocal patterns of Senegal and South African lesser bushbabies and their implications for taxonomic relationships. Folia Primatologica 51: 87–105.