Mozambique Dwarf Galago

Paragalago granti

2025 Red list status

Data Deficient

Regional Population Trend

Unknown

red list index

No Change

Overview

Paragalago granti – (Thomas & Wroughton, 1907)

ANIMALIA – CHORDATA – MAMMALIA – PRIMATES – GALAGIDAE – Paragalago – granti

Common Names: Mozambique Dwarf Galago, Grant’s Bushbaby, Grant’s Dwarf Galago, Grant’s Lesser Galago, Mozambique Lesser Galago (English), Grant se Nagapie (Afrikaans)

Synonyms: Galago granti (Thomas & Wroughton 1907), Galago senegalensis granti (Schwarz 1931), Galago zanzibaricus granti (Jenkins 1987), Galagoides zanzibaricus granti (Meester et al. 1986), Paragalago granti (Masters et al. in prep.), mertensi (Honess et al. 2013).

Taxonomic Note:

A phylogenetic analysis of the lorisiform primates by Pozzi et al. (2015) showed that Galagoides demidoff and G. thomasi comprise a clade entirely separate from the remaining species currently placed in the genus Galagoides: G. rondoensis, G. orinus, G. zanzibaricus, G. cocos, and G. granti. This latter group is sister to Galago É. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire 1796, with the two lineages diverging about 15 mya, and has been attributed to a separate genus Paragalago (Masters et al. 2017). Galagoides is now restricted to the western forms: demidoff (G. Fischer, 1806), thomasi (Elliot, 1907), and kumbirensis Svensson, Bersacola, Mills, Munds, Nijman, Perkin, Masters, Couette, Nekaris and Bearder (2017). A phylogenetic analysis of lorisiform primates by Pozzi et al. (2015) demonstrated that Galagoides demidoff and G. thomasi form a clade distinct from the remaining species currently placed in Galagoides: G. rondoensis, G. orinus, G. zanzibaricus, G. cocos, and G. granti. This latter group (G. rondoensis, G. orinus, G. zanzibaricus, G. cocos, and G. granti) was found to be sister to the genus Galago (É. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1796), with the two lineages diverging approximately 15 million years ago (mya). Based on these findings, Masters et al. (2017) reassigned these species to a newly established genus, Paragalago. As a result, the genus Galagoides is now restricted to the western dwarf galagos, consisting of: Galagoides demidoff (G. Fischer, 1806), Galagoides thomasi (Elliot, 1907) and Galagoides kumbirensis (Svensson et al., 2017).

|

Red List Status |

|

DD – Data Deficient, (IUCN version 3.1) |

Assessment Information

Assessors: Pillay, K.1 & da Silva, J.2

Reviewer: Scheun, J.3

Contributor: Patel, T.1

Institutions: 1Endangered Wildlife Trust, 2South African National Biodiversity Institute, 3Department of Nature Conservation, Tshwane University of Technology

Previous Assessors & Reviewers: Génin, F., Yokwana, A., Kom, N. & Masters, J.

Previous Contributors: Page-Nicholson, S. & Child, M.F.

Assessment Rationale

The species was only recently discovered within the boundaries of South Africa, where it is restricted to patches of sand forest in northern KwaZulu-Natal, at the southern limit of its distribution. This species is not considered a vagrant within the assessment region as there are at least two established subpopulations in the Tembe and Tshanini areas. Within its habitat, the species may not be rare, but its preferred habitat is rare enough in South Africa to mark it for conservation concern. A survey of potential areas, where Paragalago granti is likely to have been mistaken for the similar-sized Southern Lesser Galago, Galago moholi, is of primary importance for a reliable assessment of its conservation status. Until such surveys are complete, we list this species as Data Deficient due to its unknown extent of occurrence and area of occupancy. We caution, however, that habitat loss from deforestation and selective logging for firewood, combined with a potential loss in habitat quality owing to frequent fires, may already be threatening this species within the assessment region.

Regional population effects: Because vast areas covered with patches of sand forest exist in southern Mozambique, the South African population of Paragalago granti was probably not isolated until recently However, the extent of current connectivity with Mozambique populations and the likelihood of a rescue effect remains uncertain.

Recommended citation: Pillay K & da Silva JM. 2025. A conservation assessment of Paragalago granti. In Patel T, Smith C, Roxburgh L, da Silva JM & Raimondo D, editors. The Red List of Mammals of South Africa, Eswatini and Lesotho. South African National Biodiversity Institute and Endangered Wildlife Trust, South Africa.

Reasons for Change

Reason(s) for Change in Red List Category from the Previous Assessment: No change

Red List Index

Red List Index: No change

Regional Distribution and occurrence

Geographic Range

P. granti has been identified in Tembe Elephant Park and Tshanini Community Reserve (Génin et al. 2016), but the true extent of its distribution in South Africa is unknown. The species was formerly mistaken for Galago moholi, erroneously (we believe) extending the range of the latter species into northern KwaZulu-Natal. In South Africa the two small galagos are unlikely to have overlapping ranges because, while G. moholi prefers dry savannah woodlands, P. granti is apparently confined to dry sand forest. Satellite imagery indicates that the sand forest found in this region extends into southern Mozambique. P. granti occurs in Mozambique, eastern Zimbabwe, southern Tanzania, and also possibly Malawi, although it may have been mistaken for another species provisionally named Galagoides nyasae (S. Bearder pers. comm. 2015).

Elevation / Depth / Depth Zones

Elevation Lower Limit (in metres above sea level): (Not specified)

Elevation Upper Limit (in metres above sea level): (Not specified)

Depth Lower Limit (in metres below sea level): (Not specified)

Depth Upper Limit (in metres below sea level): (Not specified)

Depth Zone: (Not specified)

Biogeographic Realms

Biogeographic Realm: (Not specified)

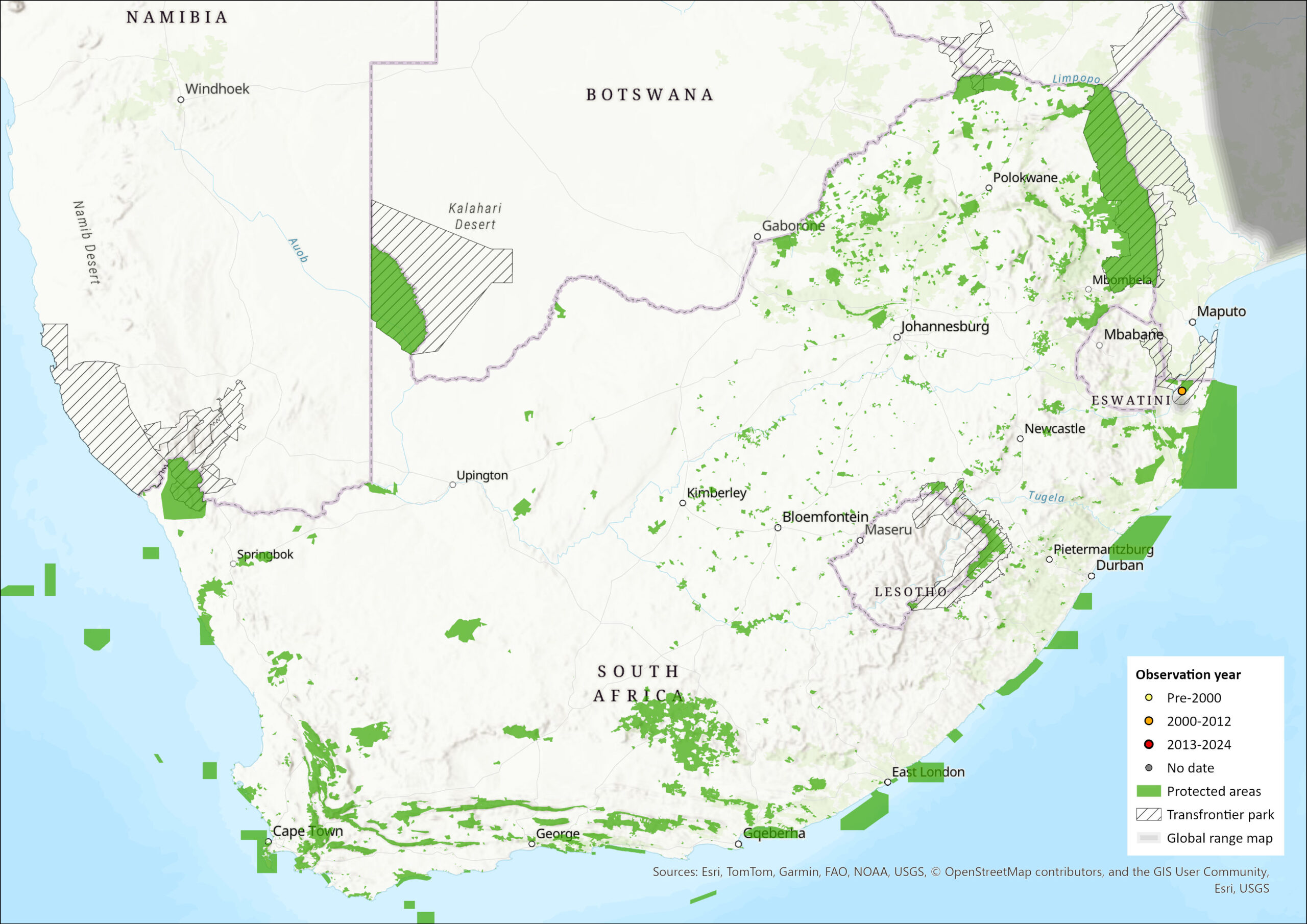

Map

Figure 1. Distribution records for Mozambique Dwarf Galago (Paragalago granti) within the assessment region (South Africa, Eswatini and Lesotho). Note that distribution data is obtained from multiple sources and records have not all been individually verified.

Countries of Occurrence

|

Country |

Presence |

Origin |

Formerly Bred |

Seasonality |

|

Eswatini |

Possibly Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

Mozambique |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

South Africa |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

|

Zimbabwe |

Extant |

Native |

– |

– |

Large Marine Ecosystems (LME) Occurrence

Large Marine Ecosystems: (Not specified)

FAO Area Occurrence

FAO Marine Areas: (Not specified)

Climate change

Climate change presents significant challenges for primate species, including P. granti, whose potential vulnerability remains under explored due to a lack of targeted studies. As a species with a restricted habitat preference for sand forests, P. granti may be particularly susceptible to shifts in temperature, changes in precipitation patterns, and the increased frequency of droughts and wildfires. These climate-induced changes could impact vegetation structure and resource availability, potentially affecting population densities, particularly in the southernmost part of its range in South Africa, where suitable habitats are already limited. Moreover, rising temperatures may increase thermoregulatory demands for primates, including P. granti, which has limited long-term coping options but may exhibit behavioural plasticity to adapt (Thompson & Hermann 2024). Understanding these behavioural mechanisms is crucial for assessing the species’ resilience to climate variability and its ability to adapt to environmental changes (Masters et al., 2017).

Population information

In Tshanini (KwaZulu-Natal), subpopulation density was estimated at 1.4 individuals / km on a linear transect (Génin et al. 2016), a very low encounter rate commensurate with the rarity of its preferred habitat (creeper-rich woodland and sand forest). For example, encounter rates in other parts of its distribution range from 1.2 to 4.9 individuals / km (Honess et al. 2013). More detailed surveys are needed to estimate the size of the population within the assessment region. Because the species uses a mosaic habitat, extrapolations are difficult.

Population Information

Current population trend: Unknown

Continuing decline in mature individuals: Unknown

Number of mature individuals in population: Unknown

Number of mature individuals in largest subpopulation: Unknown

Number of subpopulations: Two (known localities)

Severely fragmented: Yes. The sand forest is naturally fragmented and P. granti is adapted to mosaic habitats. However, dispersal between patches of suitable habitat has probably become more difficult owing to severe degradation of surrounding woodland and riverine forest.

Extreme fluctuations in the number of subpopulations: (Not specified)

Continuing decline in number of subpopulations: (Not specified)

All individuals in one subpopulation: (Not specified)

Quantitative Analysis

Probability of extinction in the wild within 3 generations or 10 years, whichever is longer, maximum 100 years: (Not specified)

Probability of extinction in the wild within 5 generations or 20 years, whichever is longer, maximum 100 years: (Not specified)

Probability of extinction in the wild within 100 years: (Not specified)

Population genetics

No population genetic study has been conducted on this species and its distribution within the assessment region is very limited. It is known from two adjacent reserves, and therefore likely supports a single population of P. granti between the two. Consequently, within the assessment region, one population is maintained (i.e., remains), resulting in a PM indicator value of 1.0 (1/1 populations remain).

Due to limited knowledge of population sizes, no estimate of effective population size (Ne) can be measured, preventing the Ne 500 indicator from being quantified.

Habitats and ecology

Mozambique Dwarf Galagos generally occur in natural, lowland evergreen and semi-evergreen forest, dry coastal forest, thicket and scrub (Honess et al. 2013). They appear to be dependent on dry sand forest in South Africa, which is where they spend their daylight hours sleeping in tree holes. Populations in Tanzania often build round, leafy nests for sleeping, and as many as five animals may share a sleeping site (Lumsden and Masters 2001, Honess et al. 2013). During the nocturnal activity period, however, they forage along the forest edges, in mature woodland with abundant lianas and creepers, and in dense thicket. The preferred habitat of the species, therefore, is a mosaic that probably antedates anthropogenic transformations of the landscape. The sand forest mosaic has a restricted distribution within the assessment region, sometimes occurring in protected areas (for example, Mkuze, Ndumo and Tembe-Tshanini), and is home to a number of rare species found at the southern limit of their distributions, including the Four-toed Elephant Shrew (Petrodromus tetradactylus) and the Suni (Neotragus moschatus). Several types of sand forest are observed from north of St Lucia to the Pongola River, including riverine sand forest (Mkuze) and dry sand forest (Tembe-Tshanini). The Mozambique Dwarf Galago was only observed in Tembe Elephant Park and the Tshanini Community Reserve, in the dry sand forest dominated by large endemic sandveld Newtonia (Newtonia hildebrandtii). This naturally fragmented habitat is limited to ancient dunes. Also confined to this habitat is another rare species, the Blue-throated Sunbird (Anthreptes reichenowi). The large game present in Tembe and Tshanini do not have a significant effect on the preferred habitat of this species. Large browsers may in fact favour the species by creating forest edges preferred by the galagos. Stocking wildlife may therefore afford protection to the sand forest mosaic habitat, particularly by limiting the harvesting of old trees, and retaining tree holes as sleeping sites.

Dwarf galagos use all the vegetation strata, and preliminary observations conducted at Tembe and Tshanini indicated a mixed diet of fruit, gum and small prey hunted in the litter, much as described for populations in Tanzania (Lumsden and Masters 2001) and Zimbabwe (Smithers 1983). Birth occurs at the commencement of the rainy season, in November to December, and twinning appears to be common (F. Génin pers. obs. 2014). Because their habitats overlap, dwarf galagos often encounter Thick-tailed Greater Bushbabies (Otolemur crassicaudatus) but individuals of the two species ignore each other and do not appear to compete. The main predators of Paragalago granti are likely to be large owls like the Spotted Eagle-Owl (Bubo africanus); they do not react defensively to the presence of smaller owl species, like the African Wood-owl (Strix woodfordi) and the Pearl-spotted Owlet (Glaucidium perlatum).

Ecosystem and cultural services: Mozambique Dwarf Galagos may be involved in pollination and seed dispersal, but their diet has not been studied in detail. They have been observed eating nectar, marula gum and insects, indicating a role in the control of insect populations. They also take vertebrates, having been seen chewing the heads of birds captured in mist nets in Zimbabwe (Smithers 1983). The presence of Mozambique Dwarf Galagos in Tembe and Tshanini may enhance the reserves’ attractiveness to wildlife enthusiasts. The animals’ small size and nocturnal lifestyle makes them rather cryptic, but they are easily detected by their calls.

IUCN Habitats Classification Scheme

|

Habitat |

Season |

Suitability |

Major Importance? |

|

1.5. Forest -> Forest – Subtropical/Tropical Dry |

– |

Suitable |

– |

|

1.6. Forest -> Forest – Subtropical/Tropical Moist Lowland |

– |

Marginal |

– |

Life History

Generation Length: (Not specified)

Age at maturity: female or unspecified: (Not specified)

Age at Maturity: Male: (Not specified)

Size at Maturity (in cms): Female: (Not specified)

Size at Maturity (in cms): Male: (Not specified)

Longevity: (Not specified)

Average Reproductive Age: (Not specified)

Maximum Size (in cms): (Not specified)

Size at Birth (in cms): (Not specified)

Gestation Time: (Not specified)

Reproductive Periodicity: (Not specified)

Average Annual Fecundity or Litter Size: (Not specified)

Natural Mortality: (Not specified)

Does the species lay eggs? (Not specified)

Does the species give birth to live young: (Not specified)

Does the species exhibit parthenogenesis: (Not specified)

Does the species have a free-living larval stage? (Not specified)

Does the species require water for breeding? (Not specified)

Movement Patterns

Movement Patterns: (Not specified)

Congregatory: (Not specified)

Systems

System: Terrestrial

General Use and Trade Information

Although there is no documented use, it is possible that the species is hunted for bushmeat.

Local Livelihood: (Not specified)

National Commercial Value: (Not specified)

International Commercial Value: (Not specified)

End Use: (Not specified)

Is there harvest from captive/cultivated sources of this species? (Not specified)

Harvest Trend Comments: (Not specified)

Threats

The number of threats and their severity for this species is unknown. They are potentially threatened by habitat destruction usually associated with human settlements. Grazing by domestic cattle has little effect on the sand forest. The Mozambique Dwarf Galago has only been found in the dry sand forest, which is located far from sources of water and sparsely populated, resulting in moderate degradation. However, ongoing forest loss from human settlement expansion, or logging of trees for firewood, may be a threat to the species. The increased frequency of fires in the area, as a result of agricultural practices or otherwise, may also decrease habitat quality.

Future surveys should investigate whether the species occurs in other, more threatened, riverine habitats, such as the gallery forest of Ndumo and Mkuze. It would be of particular interest to determine whether the species occurs west of the Pongola River where its preferred habitat seems to disappear on account of the absence of dunes.

Conservation

Although the Mozambique Dwarf Galago has a relatively large distribution range, extending north to eastern Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Malawi and southern Tanzania, its presence is only known in a few localities within the assessment region and its distribution is likely to be patchy. Conservationists often conflict with local inhabitants in this region and conservation efforts should be focused on existing protected areas that include patches of sand forest, in particular the Tshanini Community Reserve. The absence of infrastructure for tourists and researchers makes fieldwork difficult in Tshanini, but the absence of dangerous animals, such as Lions (Panthera leo) and Elephants (Loxodonta africana), means that it is the only known protected area where the species can be studied on foot. A major concern for the survival of this species in Tshanini is the frequent use of burning as a management tool by conservation managers. This practice jeopardises the mosaic woodland within which P. granti is often observed foraging, and should be reconsidered.

Recommendations for land managers and practitioners:

- Fires should spare transitional habitats used by the Mozambique Dwarf Galago, in particular patches of mature woodland rich in creepers and lianas.

Research priorities:

- A global survey is needed to assess the South African subpopulations of the Mozambique Dwarf Galago.

- A finer scale study (at Tshanini – only site accessible by foot) is equally needed to understand the ecology of the species, as almost nothing is known about its social ecology.

Encouraged citizen actions:

- Landowners with patches of sand forest should be encouraged to report sightings and allow research access to their propertiesObservers should document sightings on virtual museum and citizen science platforms (e.g., iNaturalist and MammalMAP), particularly for populations outside protected areas.

Bibliography

Bearder, S.K., Honess, P.E., Bayes, M., Ambrose, L. and Anderson, M. 1996. Assessing galago diversity – a call for help. African Primates 2: 11–15.

Butynski, T.M., de Jong, Y.A., Perkin, A.W., Bearder, S.K. and Honess, P.E. 2006. Taxonomy, distribution, and conservation status of three species of dwarf galagos (Galagoides) in eastern Africa. Primate Conservation 21: 63 –79.

GeoTerraImage. 2015. Quantifying settlement and built-up land use change in South Africa. Pretoria.

Groves, C.P. 1974. Taxonomy and phylogeny of prosimians. In: Martin, R.D., Doyle, G.A. and Walker, A.C. (eds), Prosimian Biology, pp. 449–473. Duckworth, London.

Groves, C.P. 2005. Order Primates. In: D.E. Wilson and D.M. Reeder (eds), Mammal Species of the World, pp. 111-184. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Génin F, Yokwana A, Kom N, Couette S, Dieuleveut T, Nash SD, Masters JC. 2016. A new galago species for South Africa (Primates: Strepsirhini: Galagidae). African Zoology 51: 135–143.

Honess, P.E. and Bearder, S. 1996. Descriptions of the dwarf galago species of Tanzania. African Primates 2(2): 75-79.

Honess, P.E., Bearder, S.K. and Butynski, T.M. 2013. Galagoides granti Mozambique dwarf galago. In: Butynski, T.M., Kingdon, J. & Kalina, J (ed.), Mammals of Africa. Volume 2 Primates , Bloomsbury, London.

Jenkins, P.D. 1987. Catalogue of Primates in British Museum (Natural History) and elsewhere in the British Isles. British Museum (Natural History), London, UK.

Jewitt, D., Goodman, P.S., Erasmus, B.F.N., O’Connor, T.G. and Witkowski, E.T.F. 2015. Systematic land-cover change in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: Implications for biodiversity. South African Journal of Science 111: 1-9.

Kingdon, J. 1997. The Kingdon Field Guide to African Mammals (first edition}. Academic Press, San Diego, California, USA.

Lumsden, W. H. R. & Masters, J. 2001. Galago (Galagonidae) collections in East Africa (1953–1955): ecology of the study areas. African Primates 5: 37-42.

Masters, J.C. and Couette, S. 2015. Characterizing cryptic species: a morphometric analysis of craniodental characters in the dwarf galago genus Galagoides. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 158: 288−299.

Meester, J.A.J., Rautenbach, I.L., Dippenaar, N.J. and Baker, C.M. 1986. Classification of Southern African Mammals. Monograph number 5. Transvaal Museum , Pretoria, South Africa.

Olson, T.R. 1979. Studies on Aspects of the Morphology and Systematics of the Genus Otolemur. Ph.D .Thesis, University of London.

Pozzi, L., Disotell, T.R. and Masters, J.C. 2014. A multilocus phylogeny reveals deep lineages within African galagids (Primates: Galagidae). BMC Evolutionary Biology 14: 72.

Pozzi, L., Nekaris, K.A., Perkin, A., Bearder, S.K., Pimley, E.R., Schulze, H., Streicher, U., Nadler, T., Kitchener, A., Zischler, H., Zinner, D. and Roos, C. 2015. Remarkable ancient divergences amongst neglected lorisiform primates. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 175: 661–674. doi: 10.1111/zoj.12286.

Pozzi, L., Penna, A., Bearder, S. K., Karlsson, J., Perkin, A., & Disotell, T. R. 2020. Cryptic diversity and species boundaries within the Paragalago zanzibaricus species complex. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution, 150, 106887.

Schwarz, E. 1931. On the African long-tailed lemurs or galagos. Annual Magazine of Natural History 10(7): 41–66.

Skinner, J.D. and Chimimba, C.T. (eds). 2005. The Mammals of the Southern African Subregion. Cambridge University Press, United Kingdom, Cambridge.

Smithers, R.H.N. 1983. The Mammals of the Southern African Subregion. University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa.

Thomas, O. and Wroughton, R.C. 1907. The Rudd Exploration of South Africa. VII. List of mammals obtained by Mr. Grant at Coguno, Inhambane. Journal of Zoology 77: 285–306.

Thompson CL & Hermann EA. 2024. Behavioral thermoregulation in primates: A review of literature and future avenues. American Journal of Primatology. e23614. doi: 10.1002/ajp.23614

Svensson, M.S., Bersacola, E., Mills, M.S., Munds, R.A., Nijman, V., Perkin, A., Masters, J.C., Couette, S., Nekaris, K.A.I. and Bearder, S.K., 2017. A giant among dwarfs: a new species of galago (Primates: Galagidae) from Angola. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 163(1), pp.30-43.