Leopard

Panthera pardus

2025 Red list status

Vulnerable

Regional Population Trend

Declining

Change compared

to 2016

No Change

Overview

Panthera pardus – (Linnaeus, 1758)

ANIMALIA – CHORDATA – MAMMALIA – CARNIVORA – FELIDAE – Panthera – pardus

Common Names: Leopard (English), Luiperd (Afrikaans), Ingwe (Ndebele, Swati, Tshivenda, Xhosa, Xitsonga, Zulu), Nkwe (Sesotho, Setswana), Isngwe, Mdaba (Shona)

Synonyms: Felis pardus Linnaeus, 1758

Taxonomic Note:

Kitchener et al. (2017) in their revised taxonomy of the Felidae recognizes the following eight Leopard subspecies:

- Panthera pardus pardus (Linnaeus, 1758): Africa

- Panthera pardus tulliana (Valenciennes, 1856; 1039): Turkey, Caucasus, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan

- Panthera pardus fusca (Meyer, 1794): Indian subcontinent, Myanmar and China

- Panthera pardus kotiya (Deraniyagala, 1949): Sri Lanka

- Panthera pardus delacouri (Pocock, 1930b): South-east Asia and probably southern China

- Panthera pardus orientalis (Schlegel, 1857) including japonensis: Eastern Asia from Russan Far East to China

- Panthera pardus melas (Cuvier, 1809; 152): Java

- Panthera pardus nimr (Hemprich and Ehrenberg, 1832): Arabian Peninsula

Red List Status: VU – Vulnerable, C1 (IUCN version 3.1)

Assessment Information

Assessors: Mann, G.K.H.1, Williams, K.S.2 & da Silva, J.M.3

Reviewers: Parker, D.4 & Venter, J.A.5

Contributor: Patel, T.6

Institutions: 1Panthera, 2Cape Leopard Trust, 3South African National Biodiversity Institute, 4University of Mpumalanga, 5Nelson Mandela University, 6Endangered Wildlife Trust

Assessment Rationale

The Leopard is a widespread species within the assessment region and occupies a myriad of habitats. Yet it faces severe threats, especially outside protected areas. The majority of suitable Leopard habitat in South Africa (68%) falls outside of protected areas (Swanepoel et al. 2013), posing a major consideration for conservation planning.

The most systematic current population estimate for South Africa ranges widely from 2,813–11,632 Leopards, which equates to 1,688–6,979 mature individuals (60% mature population structure) (Swanepoel et al. 2014). All subpopulations number fewer than 1,000 mature individuals except in the bushveld and lowveld biomes of Limpopo, Mpumalanga and North West Province, areas which are likely to have the highest number of Leopards (Swanepoel et al. 2014). These estimates are derived from habitat suitability models utilising occurrence data collected between 2000 and 2010. Due to the age of these data points and the extrapolatory methodology utilised, these estimates lack precision and should be treated with caution when being used to guide policy and management decisions (for example, in setting hunting quotas).

Long-term Leopard population studies in KwaZulu-Natal, Limpopo and North West provinces, weighted by population size show an overall net decline in Leopard population densities (~3% per year) (Garbett et al. 2023). There is substantial variation both within and between provinces, with Leopards in KwaZulu-Natal showing the strongest population declines (2013 – 2022: 7% decline), while populations in Limpopo (2013 – 2023: 1% increase) and North West (2016 – 2023: 4% increase) both showed positive population growth rates (Woodgate et al. 2024). The only site in Mpumalanga for which similar information is available (Timbavati Nature Reserve) showed a 3% annual decline in population density (Woodgate et al. 2024). A citizen science-based monitoring program in the Sabi Sands Game Reserve in Mpumalanga has shown that this population is stable at relatively high densities (Balme et al. 2019; Panthera, unpublished data). Little systematic long term population monitoring has been undertaken within the Cape provinces. Within Kwandwe Game Reserve (Eastern Cape), the population showed stability between 2017 and 2023 (S. Tokota, unpubl. data). Monitoring across a 10-year period in the Little Karoo (Western Cape) revealed a relatively stable population trend (Steyn 2024). Repeated surveys in the Cederberg (2017 /2018 and 2023) indicate similar density estimates, indicating population stability (Müller et al. 2022b, Cape Leopard Trust, unpubl. data). Despite the improvement in Leopard population status at some sites in Limpopo and North West in particular, the overall trend remains negative, with an average annual decline of 3% resulting in an estimated 27% decrease in the Leopard population over the 10-year period.

Thus, we list Leopards as Vulnerable C1 due to small overall population size and an estimated continuing decline of at least 10% over three generations (18–27 years). Severe declines are corroborated both by model simulations and empirical data from disparate geographical locations across Southern Africa within protected areas and private land experiencing threats known to be present in some parts of South Africa (Briers-Louw et al. 2024, Loveridge et al. 2022, Williams et al. 2017). As the majority of suitable Leopard habitat in South Africa (68%) falls outside of protected areas (Swanepoel et al. 2013) and given the lower density and survival rate of Leopards outside protected areas (Swanepoel et al. 2015b, Swanepoel et al. 2014), declines are suspected to be greater in such areas. There is a need to prioritise Leopard research outside of protected areas, especially research that can influence targeted conservation applications (Balme et al. 2014). Threats to Leopards on private land are heightened compared to protected areas, with studies in agricultural landscapes indicating comparatively low to moderate population density estimates (e.g. Bouderka et al. 2022, McKaughan et al. 2024, Faure et al. 2022, de Villiers et al. 2023). One of the few studies to report Leopard population trend outside of protected areas found a population decline of 66% over an eight-year period from 2008 to 2016 (Williams et al. 2017). Even within protected areas, declines persist if anthropogenic threats are not mitigated through careful management (Rogan et al. 2022).

Although the rate of decline between this assessment and the previous assessment is difficult to measure due to the variance in population estimates, we construe the net continuing population decline, the threat of being illegally harvested for cultural regalia (Naudé et al. 2020), risks associated with illegal and unsustainable bushmeat poaching using snares and dogs (Becker et al. 2024), and the possible increase in retaliatory persecution (Viollaz et al. 2021, Pirie et al. 2017), linked to wildlife and livestock ranch expansion, as being sufficiently threatening to justify the current listing. The reduction in legal hunting quotas, and frustration over the delays in issuing quotas due to ongoing legal processes may also contribute to reduced tolerance of Leopards by private landowners, although it is not possible to quantify whether this actually has translated into increased persecution of Leopards.

Monitoring frameworks, which enable provinces to track regional Leopard subpopulation trends should be expanded to new areas to more accurately estimate broad-scale population trends over three generations, as this species may justify for a higher threat status under A criterion. Key interventions adopted thus far include the adoption of sound harvest management regulations, and the use of faux Leopard skins as a cultural regalia substitute (Naude et al. 2020). Improved education and support for farmers to employ approaches that proactively prevent livestock predation risk have also been rolled out widely in some areas (e.g. initiatives led by NGOs such as the Cape Leopard Trust, Cheetah Outreach and the Endangered Wildlife Trust, by provincial nature conservation authorities, and by organisations such as Predation Management SA). However, a lack of easily accessible data on the management of incidents of conflict resulting from Leopard livestock depredation makes it difficult to assess the scope and scale of Leopards as a damage-causing species. Underreporting or misidentification of Leopard livestock depredation incidents adds to the dearth of information. Improved management and information sharing of damage-causing incidents involving Leopards is an important step to better understanding Leopard conflict and can inform the adoption of effective conflict mitigation strategies.

Regional population effects: Although no quantitative assessment has been done regarding the extent of suitable Leopard habitat across the southern African region, dispersal occurs between neighbouring countries (Fattebert et al. 2013). This dispersal has to some extent been facilitated by the establishment of Transfrontier Parks. However, continued human population growth and livestock/game farming along South African and neighbouring country borders (even within some Transfrontier Parks), means the associated Leopard-landowner conflict might limit the rescue effect of South Africa’s neighbouring countries (Purchase & Mateke 2008). Furthermore, Leopard subpopulations along South African borders also face similar threats like illegal harvesting, persecution, poorly managed trophy hunting and incidental snaring (Purchase & Mateke 2008; Jorge et al. 2013). As such, although the rescue effect is possible, it is unlikely to be a significant factor in reducing extinction risk within the assessment region and the regional status Vulnerable is therefore not changed.

Reasons for Change

Reason(s) for Change in Red List Category from the Previous Assessment: No change

Red List Index

Red List Index: No change

Recommended citation: Mann GKH, Williams KS & da Silva JM. 2025. A conservation assessment of Panthera pardus. In Patel T, Smith C, Roxburgh L, da Silva JM & Raimondo D, editors. The Red List of Mammals of South Africa, Eswatini and Lesotho. South African National Biodiversity Institute and Endangered Wildlife Trust, South Africa.

Please scroll horizontal on mobile to view tables

Distribution

Geographic Range

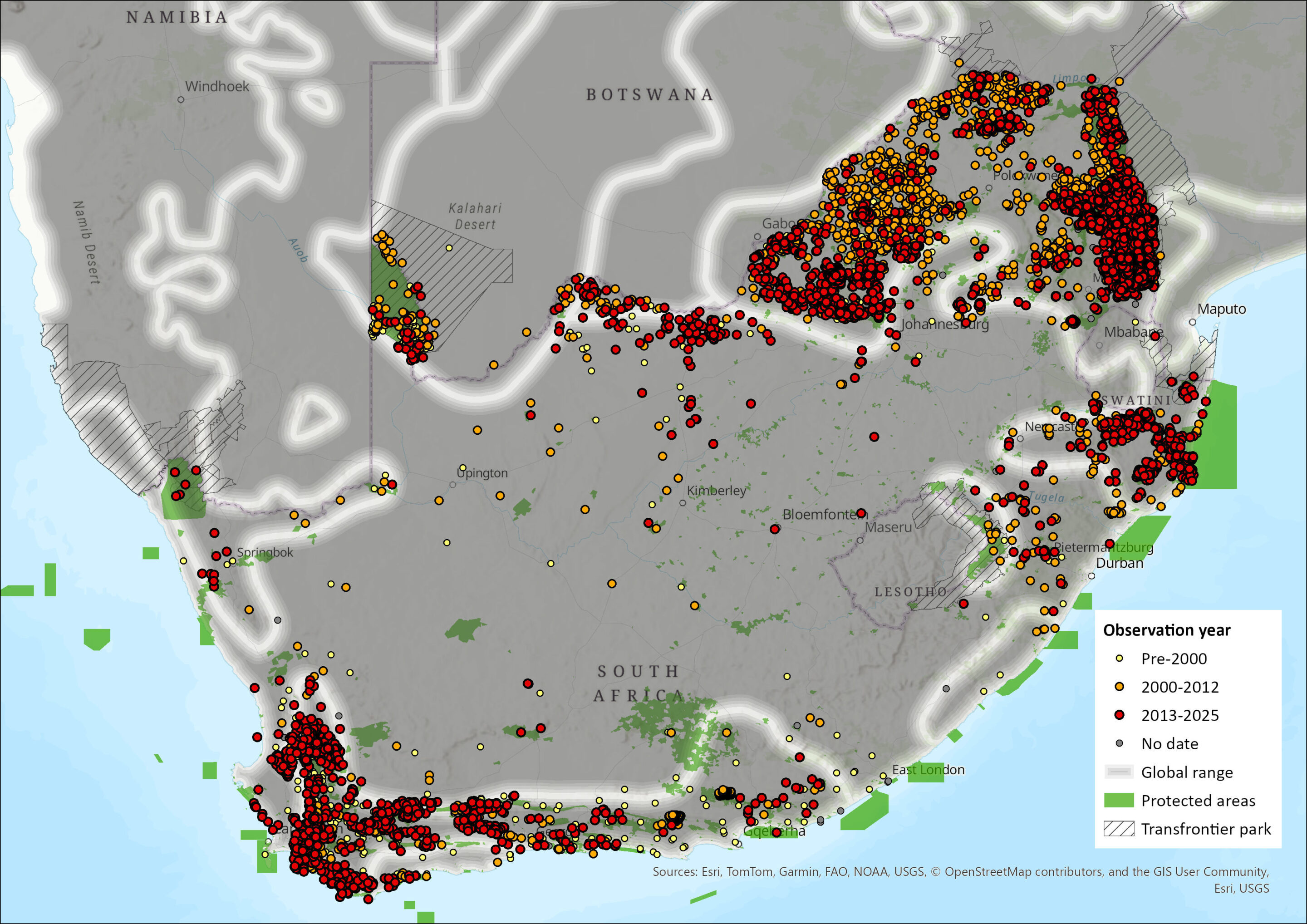

Leopards remain widely, but patchily, distributed (Stein et al. 2024) having been lost from at least 37% of their historical range in sub-Saharan Africa (Ray et al. 2005). The most marked range loss for African Leopards has been in West, Central and East Africa (Stein et al. 2024). Although southern Africa is likely to have a healthier Leopard population compared to other parts of the continent, 28–51% of their historical range in southern Africa has been lost and Leopards are thought to have been extirpated across 67% of South Africa (Jacobson et al. 2016). The species has become locally extinct in areas of high human density or extensive habitat transformation (Hunter et al. 2013). Within the assessment region, they range extensively across all provinces (except Gauteng Province, Free State Province and the greater Karoo basin in the Northern and Western Cape provinces), including Eswatini but not Lesotho; and they occur in all biomes of South Africa, with a marginal occurrence in the Nama Karoo and Succulent Karoo biomes. While Leopards were present in both Free State Province and Lesotho historically (Lynch 1983; 1994), they are very rare or absent entirely from these areas today. However, there has been a record (2014) from Clocolan, Free State Province by the Department of Economic Development, Environment, Conservation and Tourism, that occasionally attends to Leopards as damage-causing animals (N. Collins pers. comm. 2016). Additionally, Swanepoel et al. (2014) estimated that 8–26 individuals may occur in the Free State Province based on habitat suitability.

Available habitat is becoming increasingly rare: habitat suitability models classed only around 20% of South Africa as suitable habitat (Swanepoel et al. 2013). Models of suitable Leopard habitat in the Western Cape indicated variability across the landscape with the majority of potential habitats falling in protected areas and rugged / elevated areas (Greyling 2023; McManus et al. 2022b). Habitat usage for Leopards in the Cape was largely influenced by distance to protected areas, with the presence of Leopards increasing in closer proximity to and within protected areas (Greyling 2023).

Areas identified as suitable habitat should be surveyed for confirmed Leopard presence. Surveys in areas identified as Leopard habitat in Mpumalanga (Songimvelo Nature Reserve and Barberton Nature Reserve) only recorded a single Leopard photograph, while another survey in Blyde River Canyon only recorded Leopards in the northern part of the canyon, a relatively small portion of the reserve (Rogan et al. 2022). Further research and field surveys investigating spatial patterns of Leopard subpopulations outside of protected areas are needed (Balme et al. 2014). Leopards are able to disperse large distances, traversing transformed or mixed-use land. For example, an individual from Maputaland, KwaZulu-Natal Province, traversed three countries covering 353 km (Fattebert et al. 2013). In the highly fragmented Overberg region of the Western Cape, evidence from camera traps indicated male dispersal up to 112 km between origin and destination data points (Wilkinson et al. 2024). However, dispersal distances generally tend to be much smaller. A study in KwaZulu-Natal found that male Leopards dispersed an average distance of 11.0 km, with females only dispersing an average of 2.7 km (Fattebert et al. 2015). Male Leopards may remain within their natal territory in the absence of a dominant adult male (Fattebert et al. 2015). Due to the inherent difficulties and ethical considerations of collaring young male Leopards, data on dispersal is relatively sparse, and successful long-distance dispersal events should be considered the exception rather than the norm. Utilising non-invasive methods such as scat-derived genetic samples or collating historical camera trapping data from multiple sources is a valuable and cost-effective approach to reveal information on Leopard dispersal (Wilkinson et al. 2024).

Suitable Leopard habitat in South Africa has been further fragmented into four core areas, based on MaxEnt models using true positive data (Swanepoel et al. 2013), namely 1) the west coast and southeast coast of the Western and Eastern Cape Provinces; 2) the interior of KwaZulu-Natal Province; 3) the Kruger National Park and the interior of Limpopo, Mpumalanga and North West Provinces; and 4) the northern region, containing the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park (KTP) and adjacent areas of the Northern Cape and North West Provinces. There may be a fifth subpopulation in the Northern Cape covering the area including and between Namaqualand and the Richtersveld. Little is known about the current status of this population; it may be connected to the Western Cape subpopulation, but phenotypically they are more similar to Leopards elsewhere in the country (McManus et al. 2015a).

Elevation / Depth / Depth Zones

Elevation Lower Limit (in metres above sea level): 0

Elevation Upper Limit (in metres above sea level): 5200

Depth Lower Limit (in metres below sea level): (Not specified)

Depth Upper Limit (in metres below sea level): (Not specified)

Depth Zone: (Not specified)

Map

Figure 1. Distribution records for Leopard (Panthera pardus) within the assessment region (South Africa, Eswatini and Lesotho). Note that distribution data is obtained from multiple sources and records have not all been individually verified.

Biogeographic Realms

Biogeographic Realm: Afrotropical, Indomalayan, Palearctic

Occurrence

Countries of Occurrence

| Country | Presence | Origin | Formerly Bred | Seasonality |

| Afghanistan | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Algeria | Extinct | Native | – | – |

| Angola | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Armenia | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Azerbaijan | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Bangladesh | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Benin | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Bhutan | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Botswana | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Burkina Faso | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Burundi | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Cambodia | Possibly Extinct | Native | – | – |

| Cameroon | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Central African Republic | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Chad | Extant | Native | – | – |

| China | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Congo | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Congo, The Democratic Republic of the | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Côte d’Ivoire | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Djibouti | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Egypt | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Equatorial Guinea | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Eritrea | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Eswatini | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Ethiopia | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Gabon | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Gambia | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Georgia | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Ghana | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Guinea | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Guinea-Bissau | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Hong Kong | Extinct | Native | – | – |

| India | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Indonesia -> Jawa | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Iran, Islamic Republic of | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Iraq | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Israel | Extinct | Native | – | – |

| Jordan | Extinct | Native | – | – |

| Kazakhstan | Possibly Extant | Native | – | – |

| Kenya | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Korea, Democratic People’s Republic of | Possibly Extinct | Native | – | – |

| Korea, Republic of | Extinct | Native | – | – |

| Kuwait | Extinct | Native | – | – |

| Lao People’s Democratic Republic | Possibly Extinct | Native | – | – |

| Lebanon | Extinct | Native | – | – |

| Lesotho | Possibly Extinct | Native | – | – |

| Liberia | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Libya | Extinct | Native | – | – |

| Malawi | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Malaysia | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Mali | Possibly Extinct | Native | – | – |

| Mauritania | Extinct | Native | – | – |

| Morocco | Extinct | Native | – | – |

| Mozambique | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Myanmar | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Namibia | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Nepal | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Niger | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Nigeria | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Oman | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Pakistan | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Russian Federation | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Rwanda | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Saudi Arabia | Possibly Extant | Native | – | – |

| Senegal | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Sierra Leone | Possibly Extant | Native | – | – |

| Singapore | Extinct | Native | – | – |

| Somalia | Extant | Native | – | – |

| South Africa | Extant | Native | – | – |

| South Sudan | Extant | Native | ||

| Sri Lanka | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Sudan | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Syrian Arab Republic | Extinct | Native | – | – |

| Tajikistan | Possibly Extinct | Native | – | – |

| Tanzania, United Republic of | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Thailand | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Togo | Extinct | Native | – | – |

| Tunisia | Extinct | Native | – | – |

| Turkmenistan | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Türkiye | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Uganda | Extant | Native | – | – |

| United Arab Emirates | Extinct | Native | – | – |

| Uzbekistan | Possibly Extant | Native | – | – |

| Viet Nam | Possibly Extinct | Native | – | – |

| Yemen | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Zambia | Extant | Native | – | – |

| Zimbabwe | Extant | Native | – | – |

Large Marine Ecosystems (LME) Occurrence

Large Marine Ecosystems: (Not specified)

FAO Area Occurrence

FAO Marine Areas: (Not specified)

Climate change

Climate change in South Africa is characterised by rising temperatures and increased frequency of extreme weather events such as droughts, heavy rainfall and heatwaves (Johnston et al. 2024). These climatic shifts are projected to drive alterations in land-use, resource availability and agricultural patterns (Johnston et al. 2024). This, in turn, is expected to exacerbate existing anthropogenic pressures on Leopards.

Species distribution modelling under conventional climate projections indicate that the African Leopard subspecies could lose between approximately 12% (rcp4.5) and approximately 25% (rcp8.5) of its currently suitable range by 205o (Mitchell et al. 2024). This projected loss is primarily driven by climate-induced alterations in vegetation cover and corresponding shifts in the abundance, distribution and vulnerability of prey populations. Increasing aridity is expected to further impact predator-prey dynamics by reducing the vegetative cover essential for leopard ambush-hunting strategies. While southern African range contractions are predicted to be most severe in Botswana and Namibia, within South Africa, the Northern and Western Cape landscapes are identified as particularly vulnerable. In contrast, climate change may provide gains in suitable leopard habitat around the Free State.

Climatic impacts are expected to be disproportionately severe for leopard populations already experiencing high anthropogenic pressure. For instance, rising temperatures and aridity are predicted to reduce arable land productivity, potentially driving a shift towards livestock farming. Coupled with reduced prey availability, this land-use change is likely to intensify human-wildlife conflict as wide-ranging carnivores like Leopards increasingly interact with livestock (Abrahms et al. 2023). Concurrently, agricultural encroachment may expand into higher-altitude montane areas, threatening the integrity of critical habitat corridors that Leopards utilize as refugia, especially in the Western Cape (Mann et al. 2019). Such corridor disruption directly threatens population connectivity by impeding dispersal and gene flow.

Finally, indirect economic consequences of climate change also endanger leopard conservation. Impacts of climate change have been recorded in Kruger National Park, affecting species, disrupting tourism activities and damaging infrastructure (Dube and Nhambo 2020). A reduction in South Africa’s wildlife-ased tourism industry due to climate change poses a significant risk to the long-term viability of key Leopard strongholds, such as the Greater Kruger, that rely heavily on tourism-based funding models.

Population information

The Leopard is an adaptable, widespread species that nonetheless may have many threatened subpopulations. Leopard population size and trends are notoriously difficult to estimate, due to their secretive nature and the high financial costs involved in population monitoring. As such, density and population estimates can have low precision which makes interpretation difficult. The most systematic estimate (based on habitat availability and suitability, as well as a range of density estimates for each province) ranges from 2,813–11,632 Leopards, with a median (best scenario) estimate of 4,476 (Swanepoel et al. 2014). If we assume that 60% of the population is mature, (30% males, 30% females, 15% sub-adult males and females and 10% juveniles; Swanepoel et al. 2014), there are 1,688–6,979 mature individuals within the assessment region. This estimate is similar to the 4,250 estimated by Daly et al. (2005), but much lower than the 10,000 estimated by Martin and De Meulenaer (1988). The latter has been criticised as being an overestimate (Norton 1990). Such large variance makes quantitative interpretation difficult and thus these data can only be used as a rough guideline of the South African Leopard population. Caution should therefore be applied when using these data quantitatively (for example, to set hunting quotas) and robust, more recent assessment is required. The estimated generation length ranges from six years (IUCN unpubl. data) to nine years (Pacifici et al. 2013), yielding the three-generation window as 18–27 years. Leopards become sexually mature at 2.5–3 years old (Balme et al. 2013; Nowell and Jackson 1996; Skinner and Chimimba 2005) although successful reproduction at younger ages has been recorded in North West province (Power et al. 2021). First-year mortality was estimated to be 41–50% (Martin & De Meulenaer 1988; Bailey 1993) and cub survival was estimated to be only 37% (Balme et al. 2013). In South Africa, cubs reach independence from 10-18 months, and the interval between successfully raised litters varies from 16-24 months (Balme et al. 2013, 2009; Owen et al. 2010). This interval can be as short as 11 months following the loss of the previous litter (Balme et al. 2013). Average mortality of Leopard cubs prior to independence varies from 35-90% (Hunter et al. 2013).

Even populations fully insulated from human disturbance suffer juvenile mortality as high as 65% (Balme and Hunter 2013). Infanticide contributes to more than half of the mortality of juvenile Leopards in protected areas (Balme and Hunter 2013; Swanepoel et al. 2015). Mean lifetime reproductive success for female Leopards is 4.1 ± 0.8 (Balme et al. 2013). Female Leopards show a remarkable degree of parental care, which is prolonged during periods of resource scarcity, even at the expense of future offspring (Balme et al. 2017), behaviour only typical of K-selected species.

Survival rates among sub adults (1‐3 years old) is higher in protected areas (males – 82%, females – 93%) than unprotected areas (males – 67%, females – 21%) areas (Swanepoel et al. 2014). Similarly, survival of adults (>3 years) varies between protected areas (males – 91%, females – 85%) and unprotected areas (males – 72%, females – 66%) (Swanepoel et al. 2015b). The likelihood that human-carnivore conflict and thus legal Damage Causing Animal (DCA) control takes place on private land is the most likely reason for the shorter lifespans for Leopard outside of protected areas. Leopards living outside of protected areas may also be more vulnerable to accidental mortality (roadkill), incidental mortality (being caught and killed in traps or poison set for other species), or illegal mortality through targeted hunting or unauthorised damage-causing animal control.

Longevity of wild Leopards is poorly known, but females in protected areas have been recorded living to 19 years and males to 15 years (Balme et al. 2013). Leopards are thus a relatively long-lived, slow- reproducing species.

Two independent models indicate a continuing decline in the population: Daly et al. (2005) projected a continuing population decline of 16% between 2005 and 2025 under a trophy hunting quota of 150 animals per year. This is congruent with stochastic population results from Swanepoel et al. (2014), where all provincial populations showed consistent declines under a range of realistic scenarios of harvest and damage-causing animal control over the next 25 years, although overall extinction risk is low (< 10% probability).

These predictions have gained empirical support through long-term monitoring of key Leopard subpopulations in Limpopo, KwaZulu-Natal and North West provinces (Woodgate et al. 2024). Long-term Leopard population studies in KwaZulu-Natal, Limpopo and North West provinces, weighted by population size show an overall net decline in Leopard population densities (~3% per year) (Garbett et al. 2023). There is substantial variation both within and between provinces, with Leopards in KwaZulu-Natal showing the strongest population declines (2013 – 2022: 7% decline), while populations in Limpopo (2013 – 2023: 1% increase) and North West (2016 – 2023: 4% increase) both showed positive population growth rates (Woodgate et al. 2024). The only site in Mpumalanga for which similar information is available (Timbavati Nature Reserve) showed a 3% annual decline in population density (Woodgate et al. 2024). Little systematic long term population monitoring has been undertaken within the Cape provinces. Within Kwandwe Game Reserve (Eastern Cape), the population showed stability between 2017 and 2023 (S. Tokota, unpubl. data). Monitoring across a 10 year period in the Little Karoo (Western Cape) revealed a relatively stable population trend (Steyn 2024). Repeated surveys in the Cederberg (2017 /2018 and 2023) indicate similar density estimates, indicating population stability (Müller et al. 2022b) and Cape Leopard Trust, unpubl. data). Despite the improvement in Leopard population status at some sites in Limpopo and North West in particular, the overall trend remains negative, with an average annual decline of 3% resulting in an estimated 27% decrease in the Leopard population over the 10-year period.

Population Information

Continuing decline in mature individuals: Yes. From damage-causing animal control, harvesting for skins and body parts, prey depletion, snaring, and poisoning.

Extreme fluctuations in the number of subpopulations: (Not specified)

Continuing decline in number of subpopulations: (Not specified)

All individuals in one subpopulation: (Not specified)

Number of mature individuals in largest subpopulation: 5565

Quantitative Analysis

Probability of extinction in the wild within 3 generations or 10 years, whichever is longer, maximum 100 years: (Not specified)

Probability of extinction in the wild within 5 generations or 20 years, whichever is longer, maximum 100 years: (Not specified)

Probability of extinction in the wild within 100 years: (Not specified)

Population genetics

A recent phylogenetic study incorporating leopard DNA data gathered across the African continent identified two historical maternal lineages (possible evolutionarily significant units), with these lineages converging in South Africa, showing evidence of introgression in the Highveld, thereby indicating higher levels of mtDNA in the region (Morris et al. 2024).

Earlier, more finescale genetic studies were undertaken that provided insight into the more recent genetic structuring within the species. Incorporating samples from animals in the southern part of the assessment region (Western and Eastern Cape) three microsatellite genotypes were identified, but these appeared to be admixed suggesting some level of gene flow and limited geographic isolation (McManus et al. 2015). A subsequent study incorporating additional samples from across the study region, showed that southern African Leopards comprise a single metapopulation of geographically isolated groups (Ropiquet et al. 2015), with isolation by distance being a key process shaping the spatial distribution of this species’ genetic diversity and structure. This supports previous analyses (Miththapala et al. 1996; Uphyrkina et al. 2001) and confirms evidence for geographically isolated groups (for example, Western and Eastern Cape are geographically isolated from Limpopo; Tensen et al. 2011).

While measures of effective population size (Ne) have not been quantified for the metapopulation (although reanalysis of the dataset could be undertaken to obtain this metric), based on numbers of mature individuals within the assessment region (1,688–6,979, see Population section) and applying a Ne/Nc conversion ratio of 0.1-0.3, Ne is inferred to be between 169-2,098, cradling the Ne 500 threshold for a healthy and stable. Population. More accurate estimates are needed to more confidently report on the genetic health of this species.

Habitats and ecology

The Leopard has a wide habitat tolerance, including woodland, grassland savannah and mountain habitats but also occur widely in coastal scrub, shrubland and semi-desert (Hunter et al. 2013). Densely wooded and rocky areas are preferred as choice habitat types. Leopards also have highly varied diets, including more than 90 species in sub-Saharan Africa, ranging from arthropods to large antelope up to the size of adult male Eland (Tragelaphus oryx) (Hunter et al. 2013). Their main prey is in the weight range of 10–40 kg, where the preferred mass of prey is 25 kg, and, since they are solitary predators, they would generally capture prey similar to their own weight (Hayward et al. 2006). In South Africa, medium-sized ungulates such as Impala (Aepyceros melampus), Grey Duiker (Sylvicapra grimmia), and Bushbuck (Tragelaphus scriptus), are all preferred species (Hayward et al. 2006; Balme et al. 2007; Pitman et al. 2013; Williams et al. 2018), which is the case in most game reserves and ranchland country in the savannah biome where such species do occur, and thus brings Leopards into conflict with humans (for example, Power 2014). Elsewhere in the country, particularly in the montane and rocky areas of the Western Cape and Northern Cape provinces, small prey such as Rock Hyraxes (Procavia capensis) and small antelope such as Klipspringer (Oreotragus oreotragus) and Cape Grysbok (Raphicerus melanotis) are extensively utilised due to their greater availability (Bothma and Le Riche 1984; Mann et al. 2019; Martins et al. 2011; Müller et al. 2022a). This is similar to other rocky areas elsewhere, such as the Matobo National Park in Zimbabwe as determined by faecal analysis (Grobler & Wilson 1972). Livestock is recorded in some Leopard dietary studies; however, livestock generally comprises a small component of the overall diet with a preference toward natural prey over domestic species (Jansen et al. 2023; Müller et al. 2022a; Williams et al. 2018).

Leopard densities vary with habitat, prey availability, and threat severity, from fewer than one individual / 100 km² to over 30 individuals / 100 km², with highest densities obtained in protected East and southern African mesic woodland savannas (Hunter et al. 2013). Within the assessment region, the lowest densities are in the Kalahari, Eastern Cape and Western Cape (Amin et al. 2022; Bouderka et al. 2022; Devens et al. 2018; Hargey 2022; Hinde et al. 2023; Mann et al. 2020). For example, Western Cape densities range from 0.17–1.96 individuals / 100 km² (de Villiers et al. 2023, Devens et al. 2021). Density estimates for South Africa are summarised in Swanepoel et al. (2014) with additional densities in Swanepoel et al. (2015b), and more recent density estimates are contained in Rogan et al. (2022) and Woodgate et al. (2024). Leopards are not a migratory species, but their genetic viability depends on sufficient gene flow between populations (and thus dispersal) over relatively large areas. Male Leopards in the Waterberg region in Limpopo have range sizes of about 290 km² (Swanepoel 2008). The home ranges of male and female Leopards in the Kgalagadi average 2,182 km² and 488 km² respectively (Bothma 1998). In the Western Cape, Leopards occupy territories that are up to ten times larger than Leopards in Savannah regions of South Africa. In the Cederberg male home ranges are between 100 and 910 km² and female home ranges between 74 and 203 km² (Martins 2010). In the Boland Mountain Range, the average home range of males is 306 km² and a female home range was recorded at 92 km² (Chilcott 2021). In the Soutpansberg Mountains, male Leopards occupied a home range of approximately 100 km² while females occupied approximately 20 km² (S. Williams unpubl. data). In a well-protected savanna system with relatively high prey densities, female Leopards had a mean home range size of 20.2 km², while males had a mean home range size of 42.2 km² (le Roex et al. 2021).

Ecosystem and cultural services: As one of the last remaining widespread large carnivores in South Africa, Leopards may play an important role in regulating terrestrial ecosystems (Ripple et al. 2014). In the Western Cape, they have inherited the role of apex predator, impacting on mesopredator behaviour and possibly densities, such as with Caracal (Caracal caracal). In the Cederberg where Leopards and caracal have similar diets, variation in temporal and spatial activity patterns confirmed some interspecies avoidance (Müller et al. 2022a). Such regulation will depend on Leopard densities (Soulé et al. 2003), suggesting that such ecosystem services might be restricted to certain areas in South Africa. Leopards also prey upon Black-backed Jackal (Lupulella mesomelas) (Bothma and Le Riche 1994), which is a well-known problem predator species (Stuart 1981), so may control these species to some extent. Similarly, Leopards prey upon Chacma Baboons (Papio ursinus) (Pienaar 1969; Stuart & Stuart 1993, Mann et al. 2019), where they form an important prey source in the Waterberg bushveld, Soutpansberg and Western Cape mountains (Stuart & Stuart 1993; Swanepoel 2008; Jooste et al. 2013; Pitman et al. 2013; Mann et al. 2019), and thus may help to control baboon numbers.

Leopards further play an important role in the ecotourism and trophy hunting industries, where people pay significant sums of money to view and photograph, or hunt this iconic species (Balme et al. 2012). As such, they are an important flagship species for certain conservation actions and areas in South Africa. Leopards also play an important cultural role in South Africa; for example, Leopard skins are worn by members of the Nazareth Baptist (Shembe) Church as a sign of worship and by high-ranking Zulus as a status symbol (Hunter et al. 2013). Other religious groups, such as the African Methodist Church and African Congregational Church, also wear garments made from Leopard fur.

IUCN Habitats Classification Scheme

| Habitat | Season | Suitability | Major Importance? |

| 1.4. Forest -> Forest – Temperate | – | Suitable | – |

| 1.5. Forest -> Forest – Subtropical/Tropical Dry | – | Suitable | – |

| 1.6. Forest -> Forest – Subtropical/Tropical Moist Lowland | – | Suitable | – |

| 1.7. Forest -> Forest – Subtropical/Tropical Mangrove Vegetation Above High Tide Level | – | Marginal | – |

| 1.8. Forest -> Forest – Subtropical/Tropical Swamp | – | Marginal | – |

| 1.9. Forest -> Forest – Subtropical/Tropical Moist Montane | – | Suitable | – |

| 2.1. Savanna -> Savanna – Dry | – | Suitable | – |

| 2.2. Savanna -> Savanna – Moist | – | Suitable | – |

| 3.4. Shrubland -> Shrubland – Temperate | – | Suitable | – |

| 3.5. Shrubland -> Shrubland – Subtropical/Tropical Dry | – | Suitable | – |

| 3.6. Shrubland -> Shrubland – Subtropical/Tropical Moist | – | Suitable | – |

| 3.7. Shrubland -> Shrubland – Subtropical/Tropical High Altitude | – | Suitable | – |

| 3.8. Shrubland -> Shrubland – Mediterranean-type Shrubby Vegetation | – | Suitable | – |

| 4.4. Grassland -> Grassland – Temperate | – | Suitable | – |

| 4.5. Grassland -> Grassland – Subtropical/Tropical Dry | – | Suitable | – |

| 4.6. Grassland -> Grassland – Subtropical/Tropical Seasonally Wet/Flooded | – | Suitable | – |

| 4.7. Grassland -> Grassland – Subtropical/Tropical High Altitude | – | Suitable | – |

| 6. Rocky areas (eg. inland cliffs, mountain peaks) | – | Suitable | – |

| 8.1. Desert -> Desert – Hot | – | Suitable | – |

| 8.2. Desert -> Desert – Temperate | – | Suitable | – |

Life History

Generation Length: (Not specified)

Age at Maturity: 2-3 years

Size at Maturity (in cms): Female: (Not specified)

Size at Maturity (in cms): Male: (Not specified)

Longevity: up to 16 (wild) years

Average Reproductive Age: (Not specified)

Maximum Size (in cms): 130

Size at Birth (in cms): 36-48

Gestation Time: 90 days

Reproductive Periodicity: 2 years

Average Annual Fecundity or Litter Size: 2 (1-6)

Natural Mortality: (Not specified)

Breeding Strategy

Does the species lay eggs? No

Does the species give birth to live young? No

Does the species exhibit parthenogenesis? No

Does the species have a free-living larval stage? No

Does the species require water for breeding? No

Movement Patterns

Movement Patterns: Not a Migrant

Congregatory: (Not specified)

Systems

System: Terrestrial

General Use and Trade Information

Leopards are legally hunted as a trophy animal within the assessment region. When properly managed, trophy hunting should have little effect on population persistence (Swanepoel et al. 2014); however, research from KwaZulu-Natal (Balme et al. 2009; 2010b), Limpopo (Pitman et al. 2015) and Tanzania (Packer et al. 2011) suggest that poorly managed trophy hunting might lead to Leopard population declines. In South Africa, population models, which only include off-take from trophy hunting, suggested that trophy harvest levels at the time had little impact on population persistence (Swanepoel 2013; Swanepoel et al. 2014). However, when other forms of human-induced mortality (for example, legal and illegal retaliatory killing due to human-Leopard conflict) were included, trophy hunting quotas became unsustainable (Swanepoel 2013; Swanepoel et al. 2014). Additionally, there is a suspected industry in catching Leopards from the wild and providing them for the trophy hunting industry. Authorities have previously reported confiscating such animals and attempting to repatriate them elsewhere without any knowledge of their origin (R.J. Power unpubl. data).

Since the 2016 assessment, Leopard trophy hunting practices have undergone substantial reforms in order to improve the long-term sustainability of the practice. Under CITES regulations, South Africa may export up to 150 Leopards a year, but between 2008-2016 only approximately half of this number were exported (Trouwborst et al. 2019). In response to the population declines reported by the South Africa National Leopard Monitoring Project, the Leopard hunt quota was reduced to zero in 2016 and 2017 and has subsequently resumed at significantly lower levels than before (10 or fewer Leopards each year). Leopard hunts are allocated within Leopard Hunting Zones (LHZ), which ensure an even geographical spread of Leopard hunts, reducing the risk of overharvest of a particular population (Pitman et al. 2015). Only one hunt is approved within each LHZ each year, and hunts are only approved if there is evidence that the Leopard population within that LHZ is stable or has increased over a three-year period. Hunting is also restricted to mature male Leopards over seven years of age, as harvesting of this cohort has been shown to have the least impact on overall population viability (Packer et al. 2009).

The likely impacts of the illegal skin trade also need to be factored into assessments of harvest sustainability. Surveys suggest as many as 17,240–18,760 illegal Leopard skins are used by members of the Shembe Church for religious regalia and may be replaced every 3–5 years due to wear (Panthera unpubl. data). Although interviews with traders suggest many skins originate outside South Africa (Panthera unpubl. data), the trade is likely to affect Leopard population viability throughout the assessment region. Leopard derivatives are among the most profitable and widely used species within traditional medicine (Green et al. 2022; Nieman et al. 2019). Leopard parts are used for a wide variety of ailments (Nieman et al. 2019b). After the Porcupine (Hystrix africaeaustralis), Leopard was the species with the widest applicability – 15 different uses – in a traditional healer study conducted in the Western Cape (Nieman et al. 2019b). Little is known about the origin of Leopard parts sourced for traditional medicine, but the traditional medicine market may also be a driver of direct persecution.

While wildlife ranching and game farming might be increasing the amount of suitable habitat for Leopards (Power 2014), such industries can be in conflict with predators (Thorn et al. 2012), especially when breeding high-value species (Thorn et al. 2013). This was reflected by the rapid increase in the number of damage-causing animal (DCA) permit applications received from game farms in areas such as the Waterberg (Lindsey et al. 2011). An increase in ranching rare/expensive game, especially intensive breeding for trophies and colour variants, may thus impact negatively on the Leopard population through increased persecution, exclusion with predator-proof fences and limitation of gene flow. Such conflict results in two outcomes; 1) increased persecution or legal removal (DCA permits) and 2) possible exclusion through improved fencing to keep predators out. While Leopards appear to be unhindered by standard game farm fences (Fattebert et al. 2013), the quality of predator-proof fencing has improved to such an extent that it may hinder their movement between properties (du Plessis & Smit 1999).

Subsistence: No

Rationale: –

Local Commercial: Yes

Further detail including information on economic value if available: Leopards are traded locally for traditional medicine and ceremonies. Trophy hunting.

National Commercial Value: Yes

International Commercial Value: Yes

End Use: (Not specified)

Is there harvest from captive/cultivated sources of this species? No

Harvest Trend Comments: Most animals hunted will be free roaming (but see below). This includes harvest of wild Leopards for keeping in captivity.

Threats

Within the assessment region, the major threats to Leopards are habitat loss and fragmentation, and anthropogenic mortality directly through lawful and illegal killing following damage-causing incidents, and targeted poaching to meet the demand for skins and other body parts for cultural purposes (Naude et al. 2020; Nieman et al. 2019b), or incidentally through snares set by bushmeat poachers. Bushmeat poaching is also likely to have an indirect impact on Leopard populations by depleting prey populations, although the extent of these impacts is unclear across most of South Africa.

Compared to other African countries, South Africa is highly developed and thus Leopard subpopulations have become fragmented (Swanepoel et al. 2013), and there has been a long history of persecution owing to real or perceived livestock depredations (Stuart 1981; Norton 1986; Lindsey et al. 2005; St John et al. 2011). These threats are more pronounced outside protected areas (Swanepoel et al. 2015a,b), where mortality on non-protected land is due to legal and illegal damage hunting/control, snaring and poisoning, although snaring and poisoning are potentially significant causes of mortality inside protected areas too. For example, in the Soutpansberg Mountains, Limpopo Province, the most common cause of death of eight Leopards that were fitted with GPS collars between 2012 and 2015 was snaring, followed by illegal activity to protect livestock predation, such as shooting and poisoning (Williams et al. 2017). Nine separate incidents of Leopards caught in snares in the Western Cape and just beyond the boundary into the Eastern Cape were confirmed between 2012 and 2023; there is little doubt that more Leopards may have been caught in snares, but incidents went undetected or unreported (Cape Leopard Trust, unpubl. data). North West authorities, however, do mitigate this by removing snares from collared Leopards by airborne immobilisation, treatment and re-release (Power et al. 2020). Stationary Leopards are thus immediately investigated with the suspicion that they are ensnared (R.J. Power pers. obs. 2015). Snares are often set to catch game meat species such as small antelope and porcupine, species which comprise a significant proportion of the Leopard’s diet (Mann et al. 2019; Nieman et al. 2019a). Snares therefore also adversely affect Leopards by reducing their prey base (Wolf & Ripple 2016). Lower prey availability may lead to greater instances of Leopards preying on domestic livestock, leading to human-wildlife conflict and retaliatory killings of large carnivores (Wolf & Ripple 2016).

Direct persecution:

High incidences of direct persecution in South Africa reduces Leopard population size and disrupts social organisation (Balme et al. 2013, Swanepoel et al. 2014). Swanepoel et al. (2014) estimated that 35% of all Leopards killed in retaliatory actions are reproductive females. Such removals of females lead to reduced survival of Leopards (Banasiak et al. 2021a) in non-protected areas and thus affects long term population viability (Swanepoel et al. 2015b). Compounding this problem is an obvious lack of clear national conservation objectives resulting in large disparity in the number of DCA permits issued in different provinces. Direct poaching of Leopards is also suspected to be increasing due to the demand for skins (Naude et al. 2020), which may be far more severe a threat than illegal and legal problem-animal control. The traditional medicine market may also be a driver of direct persecution, as Leopard parts are used for a wide variety of ailments, but there is little confirmed data on the source of body parts (Nieman et al. 2019b). Carnivores with their large home ranges spanning multiple land use types are often caught in snares as bycatch (e.g. in the Western Cape and North West provinces) but targeted trapping and poisoning of predators for body parts appears to be on the increase in other areas (e.g. Greater Kruger)(Endangered Wildlife Trust unpubl.data). There is anecdotal evidence of a link between human-wildlife conflict and trophy hunting, as more stringent controls of trophy hunting may result in reduced tolerance for the presence of Leopards, although it is unclear whether this reduced tolerance results in increased Leopard mortality due to persecution. Finally, translocation is used as a means of resolving conflict situations but is seldom accompanied by appropriate planning or post-release monitoring (McManus et al. 2022a). Although some Leopard translocations have yielded positive results (Banasiak et al. 2021a), the outcomes of most translocations in South Africa are unknown (McManus et al. 2022), and reintroduction of large carnivores such as Leopards as a result of translocation can have negative outcomes including direct persecution if not appropriately managed (Athreya 2006; Banasiak et al. 2021b; Weilenmann et al. 2010).

Cultural regalia:

There appears to be a strong demand for Leopard skins for cultural regalia. Preliminary capture-recapture analyses suggest that members of the Nazareth Baptist Church (also known as the Shembe) may be in possession of 17,240–18,760 illegal Leopard skins with a subsequent high rate of removal from the wild (Panthera unpubl. data). This represents a significant threat to this species within the assessment region (Naude et al. 2020).

Trophy hunting:

The adoption of an adaptive management approach to trophy hunting in South Africa appears to have drastically improved trophy hunting management and reduced the additional pressure that trophy hunting may have previously placed on Leopard populations within South Africa. Unsustainable and poorly-managed trophy hunting can cause subpopulation decline (Balme et al. 2009, 2010b; Packer et al. 2011; Swanepoel 2013; Swanepoel et al. 2014). Poorly managed trophy quotas are characterised by the hunting of females, clumped harvests (excessive hunting around protected areas, and multiple tags in the same area) and hunting of inappropriate age classes (for example, excessive hunting of prime adult males) (Packer et al. 2009, 2011; Balme et al. 2012). Excessive and clumped harvest of male Leopards < 7 years old can destabilise Leopard social organisation, leading to reduced cub survival and increased female mortality (Balme et al. 2012). Similarly, hunting females can reduce overall reproductive output causing population declines (Dalerum et al. 2008). Even in countries with only male harvest, like Tanzania, females comprised 29% of 77 trophies shot between 1995 and 1998 (Spong et al. 2000).

Indirect persecution:

Snares laid out for bushmeat hunting threaten Leopards, both inside and outside of protected areas (Becker et al. 2024; Kendon et al. 2022). Poaching with dogs for bushmeat and sport / gambling, often referred to as taxi hunting, is on the rise in many areas and Leopards may fall victim to dog packs. A rapidly increasing threat is the poisoning of carcasses, either as a means of predator control or incidentally. In the Western Cape, lethal or maiming predator control methods (including gin traps, cage traps and poison) which are primarily set for mesopredators such as Caracal and Jackals also inadvertently catch Leopards (Comley et al. 2025). The rise of intensive wildlife breeding for high-value game species may also be increasing the extent of both direct and indirect persecution (Thorn et al. 2012, 2013).

Telemetry collars:

Another significant, albeit localised, threat is the injudicious use of tracking collars for research and recreational purposes. Sub-adults exhibit rapid growth and have a high neck-head circumference ratio (G. Balme unpubl. data). Collars can thus asphyxiate Leopards if they cannot be loosened or removed. Poor capture techniques also pose a threat to Leopards. 63% of projects that collared Leopards did not contribute to the scientific literature, even though some were active for over 12 years (Balme et al. 2014). It appears the motivation for much Leopard research in South Africa, particularly hands-on research such as collaring, is to enable commercial volunteer programmes, where laypeople (typically foreign graduate students) pay to experience research (Balme et al. 2014), although this practice appears to become less prevalent in recent years. North West Province have instituted the policy of controlling all Leopard collaring under their bannership and research and insist upon recaptures and collar removal via conditioning animals upon recapture.

Road collisions:

Although the effect of this threat on the population is relatively unknown, Leopards are amongst the species killed on roads, even within protected areas. Within the wider Hoedspruit area, six Leopards were killed by road collisions, and one Leopard was killed in a train collision in 2024 (Ingwe Research Program unpubl. Data). Mountain passes are especially risky for Leopards in the Cape (Cape Leopard Trust unpubl. data).

Conservation

Although Leopards occur in numerous protected areas across their range, the majority of the population occurs outside of protected areas, necessitating a need for improved conflict mitigation measures via the issuing of DCA permits as well as providing education programmes to ensure Leopards do not become locally threatened. Identifying and securing ecological corridors between suitable habitats is essential to promote human-Leopard coexistence and maintain genetic connectivity between populations (Swanepoel et al. 2013; Naude et al. 2020). This aligns with South Africa’s target to protect 30% of land by 2030 as a signatory to the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (CBD 2022).

Currently, the best strategies for Leopard conservation in South Africa can be made along three general fronts, namely policy development, land stewardship, and conflict mitigation. These can be distilled into five pillars of conservation action: 1) livestock and game conflict mitigation, 2) continuing to apply sustainable trophy hunting regulations, 3) reducing the illegal trade in skins, 4) combating illegal hunting methods and 5) protected area expansion to create a more resilient population overall.

Firstly, it is important to revise current Leopard management policies implemented by local conservation authorities and councils. These include the maintenance of stringent control methods in Leopard trophy hunting, which include age-based harvest (for example, harvest of old males; Balme et al. 2010a, 2012), enforcement of male only harvest (Balme et al. 2010a; Swanepoel et al. 2014) and non-spatial clumped harvest (Balme et al. 2010a). It is also vital to invest in rebuilding confidence and improving communication between farming communities that often bear the brunt of predation costs, and local conservation authorities. Interviews with farmers experiencing livestock depredation by Leopards in the Western Cape indicated that there is a lack of trust with the conservation authority due to perceptions of poor response time, ineffective actions and unsatisfactory capacity, a situation leading to an underreporting of conflict incidents and illegal retaliatory killing of Leopards (Viollaz et al. 2021). Furthermore, issuing permits to destroy or translocate damage-causing Leopards needs to be revised by including better conflict mitigation actions (for example, livestock guarding dogs and predator-proof fencing; McManus et al. 2015b), and implementing/monitoring mitigation actions, especially preventing the destruction of female Leopards (Swanepoel et al. 2014). Secondly, such policies being implemented by the different provincial governments must be continuously monitored with data centrally collated. These two management actions should be nationally implemented. A national monitoring framework should be established to analyse trends in Leopard off-take (via the different mortality sources) and records of conflict incidents and responses to these incidents, and to detect changes in Leopard occupancy and local densities. However, regional populations have additional threats which should be addressed at a local scale. Thus, conservationists should focus on the following interventions:

- Livestock conflict mitigation through use of guarding dogs and improved livestock husbandry (Boronyak et al. 2022; Marker et al. 2005). Various conflict mitigation projects have been established in Limpopo, North West, Northern and Western Cape provinces, but many with a carnivore community focus, rather than a focus on Leopards. Conflict events involving Leopards appear to be relatively rare in comparison to other carnivore species, such as Caracal and Black-backed Jackal across much of the country (Kerley et al. 2018; Thorn et al. 2012), and this introduces an economic conundrum for livestock farmers. It is assumed that most deterrents used for smaller carnivores will also reduce the risk of Leopard depredation but also acknowledged that the strength and mobility of Leopards makes them a particularly difficult species to defend against. Leopard attacks can be devastating mass-killing events, but happen so infrequently that it may not be worth installing extra deterrents specifically aimed at reducing Leopard depredation. The infrequency of livestock depredation events involving Leopards also make collecting data on the efficacy of these interventions difficult. Preliminary findings suggest that livestock guarding dogs can decrease depredation by all carnivores by 69% (McManus et al. 2015b). An assessment of livestock guarding dog placements on 135 farms across South Africa between 2005 – 2014 indicated that stock losses were successfully avoided following 93% of placements (Leijenaar et al. 2015). In Limpopo province, predator occupancy was not reduced by livestock guarding dogs, suggesting that the dogs do not pose a negative ecological effect on wildlife (Spencer et al. 2020). Although studies in Africa have primarily examined the advantages and challenges of employing purebred guarding dogs, indigenous local breeds which are cheaper to purchase and maintain such as Tswana dogs have proven to be as effective in Botswana with less behavioural problems (Horgan et al. 2021).

- Continued application and monitoring of more sustainable trophy hunting and damage-causing animal regulations (Balme et al. 2012), which are described above.

- Reducing the illegal trade in skins by providing faux furs for use at cultural ceremonies. Since the project began in 2013, 5,160 Leopard skins have been donated by the conservation NGO Panthera to members of the Shembe Church. Results are preliminary, but the ratio of fake to authentic skins observed at Shembe gatherings has increased from 1:8 to 1:1 (Panthera unpubl. data). However, the overall impact of the intervention on the regional Leopard population remains unknown. More generally, this also includes interventions aimed at reducing demand for anatomical parts for both ceremonial and medicinal uses.

- Carefully considered protected area expansion will also benefit this species by increasing Leopard densities in core areas, providing linkages between core areas, and creating a more resilient population as individuals are free to roam across greater areas. The most important population numerically is undoubtedly the Kruger National Park, and its adjacent private game reserves. The establishment of larger and better-connected protected areas, especially transfrontier conservation areas, will enhance metapopulation persistence, as had been modelled for Leopard in the Maputaland–Pondoland–Albany biodiversity hotspot (Di Minin et al. 2013). However, due to high levels of persecution and “edge effects”, even if new protected areas are created, success will largely depend on the attitudes, behaviour and densities of local people (Thorn et al. 2012; Balme et al. 2010b).

- Reintroduction is not recommended as a conservation tool at this stage. While there have been improvements in reintroduction success (Hayward et al. 2007), general consensus seems that translocation is of limited use in Leopard conservation (Athreya et al. 2011; Weilenmann et al. 2011). Furthermore, recent research on dispersal patterns in Leopards has demonstrated that competition for mates was the main driver for dispersal and thus dispersal increased with local subpopulation density (Fattebert et al. 2015). Therefore, interventions that increase local abundance of Leopards will also restore dispersal patterns disrupted by unsustainable harvesting and thus improve connectivity between subpopulations (Fattebert et al. 2015). Interventions that reduce the unsustainable harvesting and persecution of Leopards may also thus galvanise natural recolonisation and population dynamics.

Recommendations for land managers and practitioners:

- Existing monitoring frameworks to track provincial population trends, facilitating effective adaptive management should be maintained and, if possible, expanded to cover more areas. This could be a combination of both intensive (annual camera trap surveys in strategic sites) and extensive (change in harvest composition, hunting success and Leopard occupancy determined by trophy photographs, hunt return forms and province-wide questionnaire surveys gauging presence/absence of Leopards).

- Sustainable DCA protocols for putative problem Leopards should be adopted at a national level, where there is improved record keeping of trophy hunting and DCA permits. Integrated conservation plans are necessary. For example, in response to a fragmented (Swanepoel et al. 2013), and declining Leopard population (Power 2014), North West conservation authorities have embarked upon operations, combining law enforcement and problem animal control, to restore the species population status by reintroducing injured or problem individual Leopards. Call centres should be established to assist landowners with conflict management.

- Public awareness and education programmes should be used to encourage livestock and wildlife owners to adopt non-lethal conflict mitigation approaches to reduce the risk of depredation (Ogada et al. 2003; Rust et al. 2013; McManus et al. 2015b), or to encourage product substitution among the Shembe (and other traditional users of Leopard skins).

- Increased enforcement of the illegal killing or use of Leopard skins for cultural and religious purposes should be promoted. However, avenues should also be explored to either reduce demand for Leopard-derived items, and/or to provide a legal framework to allow for controlled access to these items from Leopards that are lawfully killed due to damage-causing behaviour, or that die of natural causes, or in captivity.

- Regular visible snare removal patrols should be incorporated in land management. Enforcement of a zero-tolerance policy for snaring is recommended. This includes forewarning all permanent and seasonal workers that snaring is illegal and will not be tolerated (include a clause in contracts).

- Avoid overharvest of key Leopard prey species, typically medium-sized antelope (between 10 and 40 kg), as well as smaller prey such as hyrax in less productive areas such as the Western Cape mountains.

Research priorities: Leopard research in South Africa is biased toward protected areas, and thus quantitative assessment of Leopard viability in the assessment region is hampered by a number of key areas of data deficiency (Swanepoel 2013; Balme et al. 2014). These include:

- The effect of land type on Leopard population status and trends: there are limited data on population sizes and trends in non-protected areas.

- Connectivity and predicted movement corridors between core areas used by Leopards.

- The scale and scope of the illegal trade in Leopard skins for cultural/religious regalia: there are limited data on illegal harvest and persecution.

- Further research and monitoring are needed on the effects of persecution and illegal harvest on population persistence, as well as the efficacy of education and awareness programmes in mitigating this threat. Greater effort will be needed to collate the number of DCA and trophy hunting permits issued.

- Research is needed to better understand illegal hunting with snares and dogs for bushmeat and sport / gambling. A large-scale database of records is required to map and investigate hotspots. Carefully planned social science investigations are needed to uncover the drivers of illegal hunting and explore potential alternatives to these activities with self-proclaimed hunters and with communities living next to protected areas.

- Research on actual versus perceived impacts on game ranches via Leopard predation (Funston et al. 2013). Conversely, investigating the impact of commercial game ranching on Leopard population persistence.

- The effectiveness of non-lethal mitigation approaches to reduce human–Leopard conflict.

- Further clarification on genetic structure of the population and likely connectivity between subpopulations.

- Relationships between Leopard landscape use and risk of road mortality.

The following research and conservation projects are currently ongoing:

- Panthera: 1) Provincial Monitoring Frameworks – partnering with provincial and national conservation authorities to establish monitoring networks to track Leopard population trends at meaningful management scales; 2) Furs for Life – combating the illegal trade in Leopard skins for cultural regalia through education, policy and the provision of faux Leopard furs. Sabi Sands Leopard Project – gathering ecological data on a well-protected Leopard population.

- Cape Leopard Trust: Combines innovative research, applied conservation, and environmental education to secure Leopard populations, protect their habitat and foster coexistence with humans in the Cape provinces. Activities include researching ecology, behaviour, and threats to Leopards; mitigating human-Leopard conflict; promoting biodiversity conservation and habitat connectivity; informing Leopard conservation and formal policy; leading environmental education and community outreach.

- Ingwe Research Program: Innovative science programs, engaging citizen scientists in wildlife monitoring, transforming data into meaningful actions for Leopard conservation. Working in and outside formally protected areas around Hoedspruit, on the western boundary of Kruger National Park.

- Landmark Leopard and Predator Project: Ecology of Leopards, remedial action for injured Leopards, and conflict management with livestock owners.

- Mpumalanga Tourism and Parks Board: Greater Lydenburg area; Kruger National western boundary carnivore monitoring, including the neighbouring rural areas; spatial ecology, habitat utilisation, population demographics and conservation of Leopards in the Loskop Dam Nature Reserve.

- North West Leopard Project: Investigating the ecology of Leopards in the province through camera trapping and GPS collars, and threats to Leopards (such as snaring), with a view to enable province-wide management (for example, setting quotas, conflict management, threat mitigation and translocation appraisal).

- Primate and Predator Project: Conducting research into the status of Leopards outside of protected areas and in the Soutpansberg Mountains, Limpopo Province.

Encouraged citizen actions:

- Report sightings on virtual museum platforms (for example, iNaturalist, MammalMAP, African Carnivore Wildbook (https://africancarnivore.wildbook.org/submit.jsp)), especially outside protected areas. Sightings and signs of Leopards in the Cape provinces can be shared to the Cape Leopard Trust’s Leopard Data Portal (https://app.capeLeopard.org.za/).

- Conduct camera trapping surveys and submit data to local conservation authority.

- Conduct snare removal on private land. Report snares found in the Cape provinces (https://app.capeLeopard.org.za/).

- Drive slowly and carefully through Leopard habitats to avoid hitting and injuring / killing animals.

- Pressure government authorities to pursue criminal cases involving this species.

Bibliography

Abrahms, B., Carter, N. H., Clark-Wolf, T., Gaynor, K. M., Johansson, E., McInturff, A., Nisi, A.C., Rafiq, K., West, L. 2023. Climate change as a global amplifier of human–wildlife conflict. Nature Climate Change, 13(3), 224-234.

Amin, R., Wilkinson, A., Williams, K.S., Martins, Q.E., Hayward, J., 2022. Assessing the status of Leopard in the Cape Fold Mountains using a Bayesian spatial capture-recapture model in Just Another Gibbs Sampler. Afr. J. Ecol. 60, 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/aje.12944

Athreya, V. 2006. Is relocation a viable management option for unwanted animals?–The case of the leopard in India. Conservation and Society, 4(3), pp.419-423.

Athreya V, Odden M, Linnell JD, Karanth KU. 2011. Translocation as a tool for mitigating conflict with Leopards in human-dominated landscapes of India. Conservation Biology 25: 133-141.

Bailey, T.N. 1993. The African Leopard: Ecology and Behavior of a Solitary Felid. Columbia University Press, New York, USA.

Balme GA, Batchelor A, Woronin Britz N, Seymour G, Grover M, Hes L, Macdonald DW, Hunter LT. 2013. Reproductive success of female Leopards Panthera pardus: the importance of top-down processes. Mammal Review 43: 221-237.

Balme GA, Hunter LT, Braczkowski AR. 2012. Applicability of age-based hunting regulations for African Leopards. PloS One 7: e35209.

Balme GA, Hunter LT, Goodman P, Ferguson H, Craigie J, Slotow R. 2010a. An adaptive management approach to trophy hunting of Leopards Panthera pardus: a case study from KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. In: Macdonald DW, Loveridge AJ (ed.), Biology and Conservation of Wild Felids, pp. 341-352. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Balme GA, Hunter LT, Slotow R. 2007. Feeding habitat selection by hunting Leopards Panthera pardus in a woodland savanna: prey catchability versus abundance. Animal Behaviour 74: 589-598.

Balme GA, Lindsey PA, Swanepoel LH, Hunter LTB. 2014. Failure of research to address the rangewide conservation needs of large carnivores: Leopards in South Africa as a case ctudy. Conservation Letters 7: 3-11.

Balme, G.A., Robinson, H.S., Pitman, R.T., Hunter, L.T.B., 2017. Flexibility in the duration of parental care: Female Leopards prioritise cub survival over reproductive output. J. Anim. Ecol. 86, 1224–1234. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.12713

Balme GA, Slotow R, Hunter LT. 2009. Impact of conservation interventions on the dynamics and persistence of a persecuted Leopard (Panthera pardus) population. Biological Conservation 142: 2681-2690.

Balme GA, Slotow R, Hunter LTB. 2010b. Edge effects and the impact of non-protected areas in carnivore conservation: Leopards in the Phinda–Mkhuze Complex, South Africa. Animal Conservation 13: 315-323.

Balme, G.A. and Hunter, L.T. 2013. Why leopards commit infanticide. Animal Behaviour, 86(4), pp.791-799.

Balme, G., Rogan, M., Thomas, L., Pitman, R., Mann, G., Whittington‐Jones, G., Midlane, N., Broodryk, M., Broodryk, K., Campbell, M. and Alkema, M. 2019. Big cats at large: Density, structure, and spatio‐temporal patterns of a leopard population free of anthropogenic mortality. Population Ecology, 61(3), pp.256-267.

Banasiak, N.M., Hayward, M.W., Kerley, G.I.H., 2021a. Ten Years on: Have Large Carnivore Reintroductions to the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa, Worked? Afr. J. Wildl. Res. 51. https://doi.org/10.3957/056.051.0111.

Banasiak, N.M., Hayward, M.W., Kerley, G.I.H., 2021b. Emerging Human–Carnivore Conflict Following Large Carnivore Reintroductions Highlights the Need to Lift Baselines. Afr. J. Wildl. Res. 51. https://doi.org/10.3957/056.051.0136

Becker, M.S., Creel, S., Sichande, M., De Merkle, J.R., Goodheart, B., Mweetwa, T., Mwape, H., Smit, D., Kusler, A., Banda, K., Musalo, B., Bwalya, L.M., McRobb, R., 2024. Wire-snare bushmeat poaching and the large African carnivore guild: Impacts, knowledge gaps, and field-based mitigation. Biol. Conserv. 289, 110376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2023.11037

Boronyak, L., Jacobs, B., Wallach, A., McManus, J., Stone, S., Stevenson, S., Smuts, B., Zaranek, H., 2022. Pathways towards coexistence with large carnivores in production systems. Agric. Hum. Values 39, 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-021-10224-y

Bothma, J du P. and Le Riche, E.N. 1984. Aspects of the ecology and the behaviour of the leopard Panthera pardus in the Kalahari Desert. Koedoe, 27(2), pp.259-279.

Bothma J du P, le Riche EAN. 1994. Scat analysis and aspects of defecation in northern Cape Leopards. South African Journal of Wildlife Research 24: 21-25.

Bothma J du P. 1998. A review of the ecology of the southern Kalahari Leopard. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa 53: 257-266.

Bouderka, S., Perry, T.W., Parker, D., Beukes, M., Mgqatsa, N., 2022. Count me in: Leopard population density in an area of mixed land‐use, Eastern Cape, South Africa. Afr. J. Ecol. 61, 228–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/aje.13078

Briers‐Louw, W.D., Kendon, T., Rogan, M.S., Leslie, A.J., Almeida, J., Gaynor, D. and Naude, V.N. 2024. Anthropogenic pressure limits the recovery of a postwar leopard population in central Mozambique. Conservation Science and Practice, 6(5), p.e13122.

Chilcott, G., 2021. Spatial ecology of the Cape’s apex predator: A study of Leopard (Panthera pardus) home ranges in the Boland Mountain Complex, Western Cape, South Africa (M.Sc.). Royal Veterinary Clinic, University of London, London.

Comley, J., van Tonder, J., Greyling, E., Wilkinson, A., Williams, K. S., Annecke, W. J., & Leslie, A. J. 2025. Unveiling threat patterns for leopards and mesopredators in agricultural landscapes of South Africa. People and Nature, 7(10), 2291-2306. http://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.70127

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). 2022. Decision adopted by the conference of the parties to the convention on biological diversity 15/4. Kunming-Montreal global biodiversity framework. https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-15/cop-15-dec-04-en.pdf

Dalerum F, Shults B, Kunkel K. 2008. Estimating sustainable harvest in wolverine populations using logistic regression. The Journal of Wildlife Management 72: 1125-1132.

Daly, B., Power, J., Camacho, G., Traylor-Holzer, K., Barber, S., Catterall, S., Fletcher, P., Martins, Q., Martins, N., Owen, C., Thal, T. & Friedmann, Y. 2005. Leopard (Panthera pardus) PHVA. Workshop Report. Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (SSC/IUCN), CBSG South Africa, Endangered Wildlife Trust.

Devens, C., Tshabalala, T., McManus, J., Smuts, B., 2018. Counting the spots: The use of a spatially explicit capture–recapture technique and GPS data to estimate Leopard ( Panthera pardus ) density in the Eastern and Western Cape, South Africa. Afr. J. Ecol. 56, 850–859. https://doi.org/10.1111/aje.12512.

Devens, C.H., Hayward, M.W., Tshabalala, T., Dickman, A., McManus, J.S., Smuts, B. and Somers, M.J. 2021. Estimating leopard density across the highly modified human-dominated landscape of the Western Cape, South Africa. Oryx, 55(1), pp.34-45.

de Villiers, M.S., Janecke, B.B., Müller, L., Amin, R. and Williams, K.S. 2023. Leopard density in a farming landscape of the Western Cape, South Africa. African Journal of Wildlife Research, 53(1).

Di Minin E, Hunter LT, Balme GA, Smith RJ, Goodman PS, Slotow R. 2013. Creating larger and better connected protected areas enhances the persistence of big game species in the Maputaland–Pondoland–Albany biodiversity hotspot. PloS One 8: e71788.

Dube, K., & Nhamo, G. 2020. Evidence and impact of climate change on South African national parks. Potential implications for tourism in the Kruger National Park. Environmental Development, 33, 100485.

Du Plessis H, Smit GN. 1999. The Development and Final Testing of an Electrified Leopard Proof Game Fence on the Farm Maseque. Department of Animal, Wildlife and Grassland Sciences, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa.

Fattebert J, Balme G, Dickerson T, Slotow R, Hunter L. 2015. Density-dependent natal dispersal patterns in a Leopard population recovering from over-harvest. PLoS One 10: e0122355.

Fattebert J, Dickerson T, Balme G, Slotow R, Hunter L. 2013. Long-distance natal dispersal in Leopard reveals potential for a three-country metapopulation. South African Journal of Wildlife Research 43: 61-67.

Faure, J.P.B., Swanepoel, L.H., Cilliers, D., Venter, J.A. and Hill, R.A. 2022. Estimates of carnivore densities in a human-dominated agricultural matrix in South Africa. Oryx, 56(5), pp.774-781.

Funston PJ, Groom RJ, Lindsey PA. 2013. Insights into the management of large carnivores for profitable wildlife-based land uses in African savannas. PloS One 8: e59044.

Garbett, R., Mann, G.K.H., Pitman, R.T., Berndt, J., Morar, S., Dubay, S.M., Tawira, V., Foden, L., Basson, A., Balme, G.A., 2023. South African Leopard Monitoring Project: Report on 2022 Leopard monitoring activities for the South African National Biodiversity Institute (No. 2022). Panthera, Cape Town.

Green, J., Hankinson, P., De Waal, L., Coulthard, E., Norrey, J., Megson, D., D’Cruze, N., 2022. Wildlife Trade for Belief-Based Use: Insights From Traditional Healers in South Africa. Front. Ecol. Evol. 10, 906398. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2022.906398

Greyling, E., 2023. Conserving corridors: An integrated landscape modelling approach to facilitate Leopard (Panthera pardus) conservation in the Western Cape, South Africa (M.Sc). Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch.