Unsustainable anthropogenic mortality threatens the long-term viability of lion populations in Mozambique

By Dr Samantha Nicholson, Senior Carnivore Scientist & Manager of the African Lion Database

Mozambique, home to Africa’s seventh largest lion population with an estimated 1,500 mature individuals, faces a critical challenge: its lions are being pushed towards an unsustainable future.

A recent study by Almeida et al. (2025) highlighted the escalating threat of human-induced mortality to lion populations across Mozambique. Still recovering from decades of warfare, these populations contend with ongoing conflicts, widespread socio-economic fragility, and the alarming reality of being a regional hotspot for the illegal wildlife trade (IWT), particularly for targeted lion poaching.

The study, in which the Endangered Wildlife Trust participated, set out to quantify the devastating impact of human-caused deaths – or anthropogenic mortality – on Mozambique’s lion populations between 2010 and 2023, and to project their future viability under varying detection rates of these mortalities. The researchers compiled extensive monitoring records and national population estimates to analyse these trends and predict future scenarios for these vulnerable populations.

Alarming Findings: The Rising Threat of Anthropogenic Pressures

The study alarming key findings show that between 2010 and 2023, a staggering 326 incidents of human-caused mortality, involving 426 individual lions, were recorded. This represents an average of about 30 lion deaths annually, with a concerning surge over the 13-year period, from 9 to 49 annual mortalities. Demographically, male lions were disproportionately affected, accounting for 68% of known mortalities compared to 32% for females, with adults making up the vast majority (83%) of the victims.

Illegal activities were the most common cause of unnatural mortality; responsible for 65% of all lion mortalities. These included lions caught as bycatch in snares (27%), targeted poaching for their body parts (25%), and retaliatory killings (13%). Legal trophy hunting accounted for the remaining 33% of incidents. Over time, there was a significant increase in bushmeat bycatch and targeted poaching, while legal trophy hunting incidents decreased.

The methods used for killing also shifted, with an increase in poisoning and snaring, and a decrease in shooting.

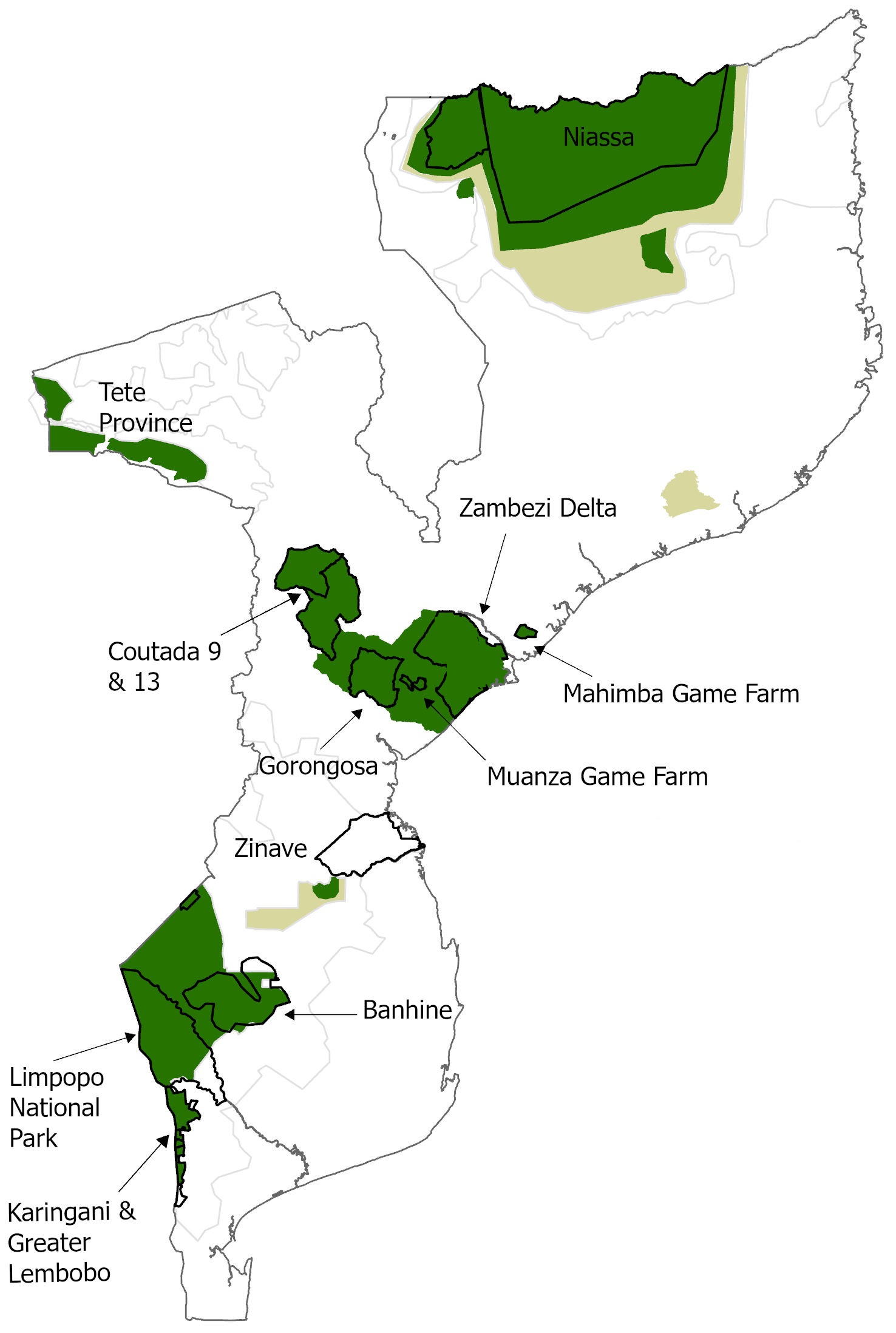

Regional differences in motives were stark: targeted poaching and retaliatory killings were most prevalent in the southern region, bushmeat bycatch dominated the central region, and the northern region primarily faced threats from trophy hunting and targeted poaching. Specifically, targeted poaching of lions for their body parts saw a dramatic rise, jumping from an average of one lion per year between 2010 and 2017 to a shocking seven lions per year between 2018 and 2023.

The study also delved into perceived threats and management capacity.

The Perceived Anthropogenic Threat Index (ATI) indicated the highest threat levels in Coutada 13 and Niassa Special Reserve (SR). Conversely, the Perceived Resource and Capacity Index (RCI), which gauges the availability of resources and management capability to reduce lion mortality, was lowest for Niassa SR, Coutadas 9/13, and the Tchuma Tchato Community Programme, indicating a significant lack of resources in these areas – Niassa having the largest lion population in the country and a known stronghold for the species.

Population viability modelling revealed wide variations in the detection rates of human-caused lion deaths across different conservation areas. Gorongosa National Park (NP), Coutadas 9/13, and the Zambezi Delta demonstrated nearly complete detection (around 100%), which instils high confidence in their population projections. This high detection rate is largely attributed to these areas having sufficient resources for monitoring and effective management strategies, such as intensive lion-specific monitoring and robust anti-poaching coverage.

However, for Niassa SR in the northern region, the detection rate was estimated to be a worryingly low 20%. This implies that its reported annual human-caused mortality rate of 3.2% is likely a severe underestimation, with the true rate potentially around 16%. Similarly, Limpopo NP had a low detection rate (20-40%), suggesting a much higher actual mortality rate, ranging from 19.8% (without the buffering effect of connectivity to Kruger NP) to approximately 40% (with Kruger NP connectivity).

Future Projections: A Bleak Outlook Without Intervention

Future projections extending to 2040 paint a stark picture: without significant interventions, most lion populations in Mozambique are predicted to either remain suppressed or face further decline. Gorongosa NP offers a glimmer of hope, showing the highest projected annual growth rate of 6.5% and expected to reach its ecological carrying capacity by 2040, thanks to its low mortality rates and effective management. In contrast, Niassa SR’s population is projected to stagnate at roughly half its ecological carrying capacity, showing a concerning tendency towards decline, a direct consequence of its high mortality and low detection rates. Most alarmingly, Limpopo NP is projected to face functional extirpation by as early as 2030 if it loses the crucial buffering effect of its neighboring Kruger National Park. This dire forecast is a result of its small population size coupled with unsustainable levels of human-caused deaths.

Recommendations: Paving the Way to Reduce the Threat

This study powerfully underscores the urgent need for national-scale action to safeguard Mozambique’s lions. To counter these critical threats, the researchers put forth several vital recommendations: it is essential to improve monitoring of lion populations and human-caused mortalities by establishing standardized systems, which will provide more accurate data for assessing trends, evaluating interventions, and establishing evidence-based quota setting. Furthermore, enhanced site security and more effectively coordinated anti-poaching operations, including the development of integrated inter-agency task forces, are crucial for bolstering regional security and alleviating pressure on local lion populations. Addressing the illegal wildlife trade necessitates targeted investigations to disrupt IWT networks and direct intervention with judiciary systems to sensitise magistrates, ensuring a robust understanding and consistent application of wildlife laws.

While acknowledging legal trophy hunting’s vital role in funding, especially in Niassa where it covers about 30% of operational costs, the authors cautiously suggest compensating for illegal human-caused mortalities within quota setting to temporarily aid local population recovery. To bridge financial shortfalls, it is recommended to develop alternative wildlife-related investment opportunities and foster tripartite partnerships among government, hunting operators, and NGOs.

Attracting greater inward investment into the conservation sector is paramount, requiring local government to create a long-term enabling environment through clear policies on public-private partnerships, simplifying bureaucracy, and streamlining engagement processes. Crucially, all conservation actions and funding models must be designed around the needs and opportunities of local communities, ensuring they become enfranchised stakeholders in lion conservation with clear incentives to coexist with these magnificent animals.

Almeida, J., Briers-Louw, W.D., Jorge, A., Begg, C., Roodbol, M., Bauer, H., Loveridge, A., Wijers, M., Slotow, R., Lindsey, P. and Everatt, K., 2025. Unsustainable anthropogenic mortality threatens the long-term viability of lion populations in Mozambique. PLoS One, 20(6), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0325745