Taking Flight over the Karoo Vulture Safe Zone: 5 years later

Taking Flight over the Karoo Vulture Safe Zone: 5 years later

By Danielle du Toit, field officer Birds of Prey, Endangered Wildlife Trust.

Returning Cape Vultures (Gyps coprotheres) to their historic breeding and roosting sites has been a dream of Karoo farmers for many years.

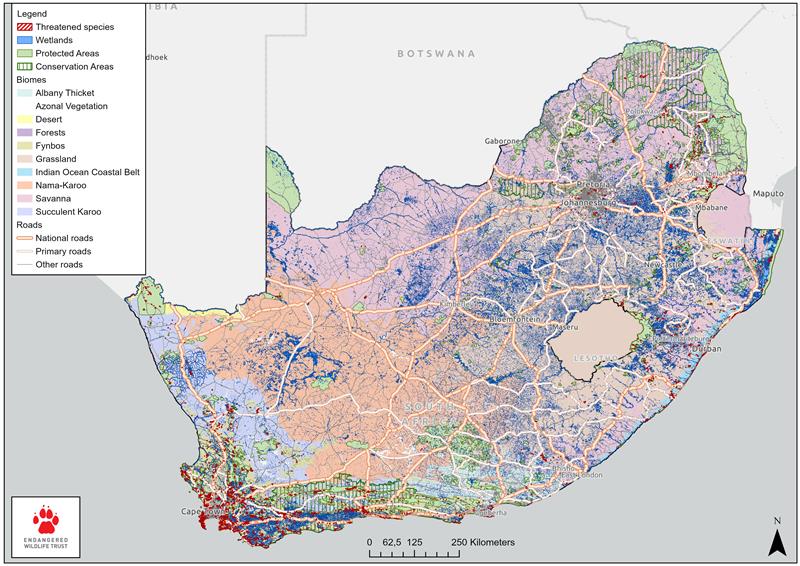

It was through interaction with the Endangered Wildlife Trust that the Karoo Vulture Safe Zone came into being in 2019. The project, which is a practical example of landscape conservation of a species, aims to cover 23,000 square kilometers. It includes three national parks and the largest protected environment in South Africa, the Mountain Zebra Camdeboo Protected Environment. It was implemented in partnership with SANParks, the Mountain Zebra Camdeboo Protected Environment and SANParks Honorary Rangers, and has received seed funding from the Rupert Nature Foundation and further funding from Cennergi and the Charl van der Merwe Trust.

To date, 95 farmers have dedicated their properties to becoming Vulture Safe Zones, creating an area of more than 700,000 ha for vulture conservation. Dedicating or signing up one’s property for a Vulture Safe Zone means that they are committed to reducing, as far as possible, threats to vultures within the confines of land under their ownership.

In creating the Vulture Safe Zone, two options were considered—reintroducing Cape Vultures to the Karoo or creating an area that is safe for the raptors. Unfortunately, reintroduction was not an option at the time due to the exceedingly high cost of physically bringing in the birds and habituating them, without any assurance that they would stay. More importantly, however, was the need to ensure safe breeding, roosting and foraging ranges for them outside of protected areas.

Vultures are referred to as nature’s ‘clean-up crew’, and because of the importance of their role in the ecosystem and the benefit to human health, they are often used as a flagship or umbrella species through which we can conserve biodiversity. By implementing conservation interventions to support the survival of vultures across large areas, we can benefit all species. This includes other birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, invertebrates and even plants.

The need for large areas to be conserved and mitigated of threats as far as possible is integral to the conservation of Cape Vultures due to their characteristically wide-ranging behaviour. Studies and GPS tracking data of fledglings have shown an average maximum distance travelled per day to be well over 250km from their nests. This age group is most likely to fall victim to threats as they are not yet experienced fliers and must compete with adults for food and roosting spaces. This is why having large safe spaces, even if it is a conglomerate of private properties, communal land and protected areas, is so important to the survival of the species.

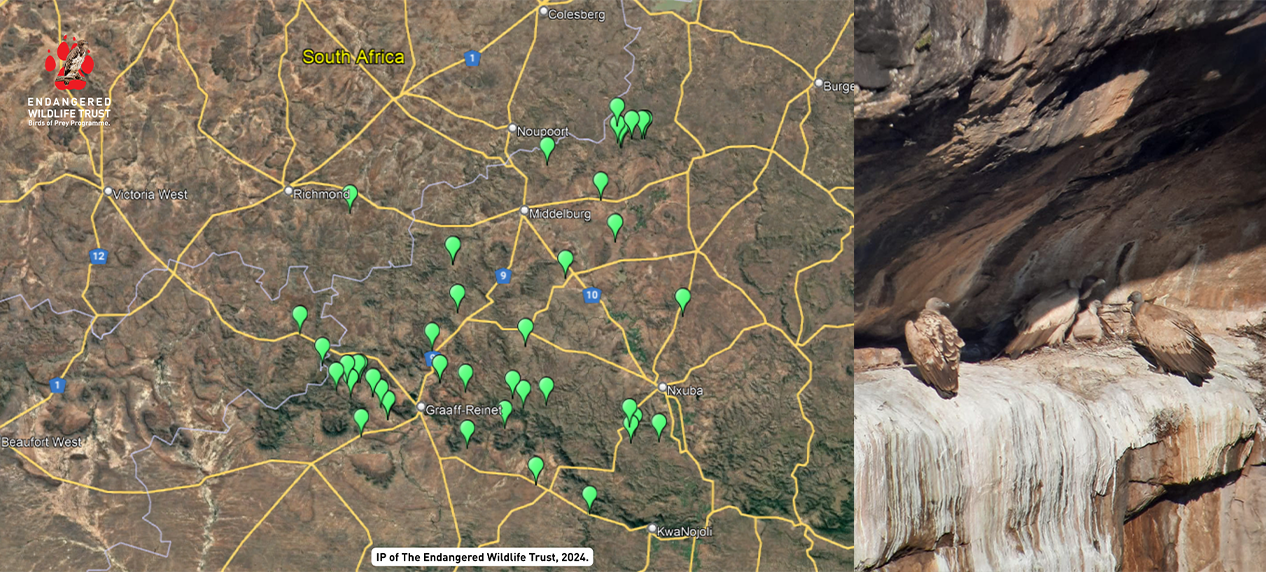

Left: Cape Vulture Sightings. Right: Cape Vultures on nest.

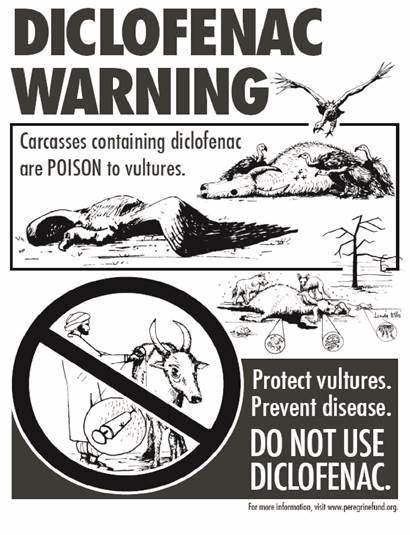

The project focuses on “working with people, mitigating threats, saving vultures”. This can only be achieved through community engagement, landowner buy-in and active mitigation of threats. These initiatives include covering or safe-proofing reservoirs to prevent drowning; changing to less ecologically harmful ways of predator control; removing dangerous chemicals from the property; and reporting wildlife injuries or mortalities caused by electrical infrastructure so that they can be mitigated. Some landowners have moved away from using lead ammunition as the fragments in the entrails or carcasses of animals shot with lead bullets can be harmful to scavenging species. Others have changed the active ingredient in their non-steroidal anti-inflammatory veterinary drugs (NSAIDs) to ensure that carcasses of animals that have been treated prior to their death are not contaminated with drugs that can harm scavenging bird species, like these vultures.

Besides the ecological importance of the Cape Vulture, this area also holds a special place for farmers and residents in the heart of the Karoo. Historically, Cape Vultures roamed the Karoo in large numbers. Many farmers have childhood stories focused solely on them. Whether it be how they would seek out their nests on horseback, climbing up the mountains that hugged the borders of their properties, or how they would simply looked up into the sky in search of a rain cloud and instead found these magnificent birds littering the air in the hundreds, stories are littered with memories of vultures.

The Karoo covers around 400,000 square kilometers of brittle ecosystems. It is an area known for its rich biodiversity with large varieties of plants, birds, insects and mammals that occur naturally on private and public land.

Through the Vulture Safe Zone relationships created between the EWT, private landowners and national parks, the project has been able to bridge the gap between agriculture, tourism and conservation. This promotes a sustainable business model for all sectors and decreases the potential of human-wildlife conflict through targeted conservation measures and holistic approaches.

The project is still in its infancy, but has already seen successes including an increase in sightings, repopulation of historic summer roosts and the willingness and eagerness of people to take part in this project in whichever way they can. The hope remains that through landscape- and farm-level threat mitigation, collaboration with all stakeholders and role players, and a multi-pronged approach driven by robust science and understanding of the species, region and people, the Cape Vultures will once again call the Karoo home.

For more information, please contact the Karoo Vulture Safe Zone Field Officer: Danielle du Toit, email: danielled@ewt.org or Gareth Tate, Birds of Prey Manager at garetht@ewt.org

Left: reservoir mitigation – tanks in dams. Right: drowned vulture in Namibia

Raptor protector on powerline