Caught on Camera: Insights into the Secret Life of Kloof Frogs

Science Snippet

Caught on Camera: Insights into the Secret Life of Kloof Frogs

By Erin Adams and Lizanne Roxburgh, Conservation Science and Planning Unit at the endangered wildlife trust

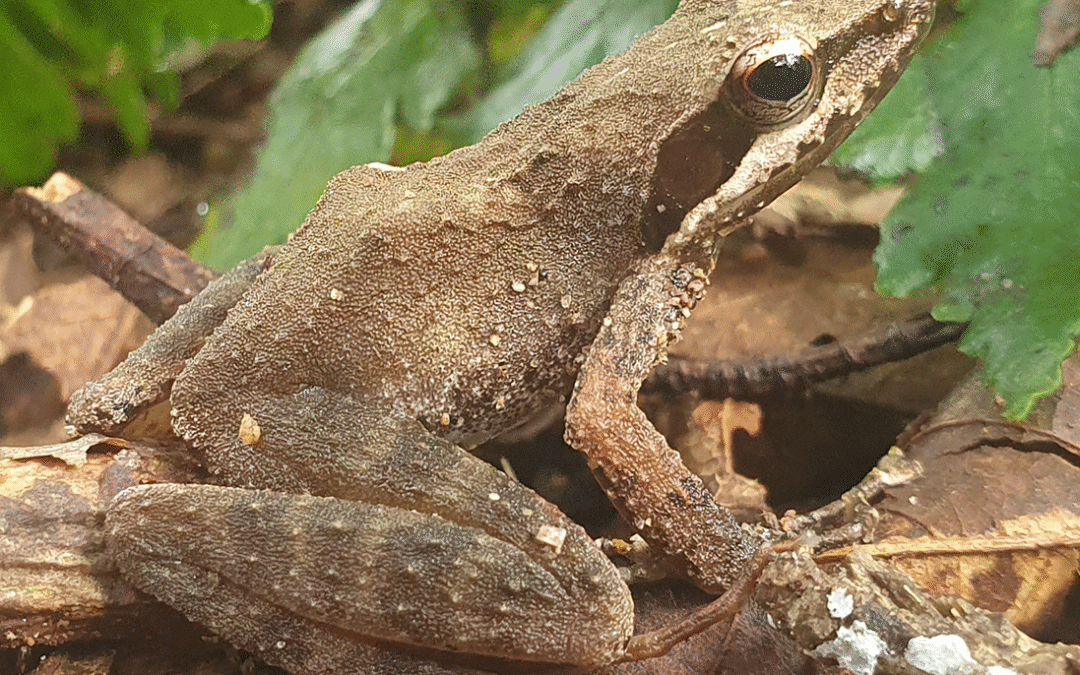

Kloof frog. Photo Credit Cherise Acker-Cooper

Camera traps are an essential tool for wildlife research, allowing scientists to monitor animals over long periods without disturbing them. They provide insights into behaviour, population trends, and habitat use.

While widely employed for studying larger animals, their potential for amphibian research has been overlooked, despite the alarming decline of these species—41% of the world’s amphibians and 23% of South Africa’s frog species face threats, such as habitat loss and climate change. Understanding their behaviour can guide conservation strategies to protect vulnerable populations.

To address this gap, EWT scientists* tested camera traps on the Endangered Kloof Frog (Natalobatrachus bonebergi), a species known for returning to the same breeding sites year after year. Their unique expanded toe tips allow them to climb slippery surfaces, enabling them to lay eggs on rocks, branches, and leaves above slow-moving streams. This placement ensures that once the tadpoles hatch, they can drop directly into the water below—a crucial survival strategy. Scientists aimed to document frog behaviour during both breeding and non-breeding seasons and analyse how environmental conditions influence their activities.

To gather data, researchers positioned camera traps along a stream where Kloof Frogs consistently breed. The cameras captured images between 18:00 and 06:00, when the frogs were active. Normally, camera traps are triggered to take a photo by the movement of animals, but Kloof Frogs are too small, so the cameras automatically took photos every minute. The images were analysed to categorise behaviours, measure the duration of the behaviour, and record the time of day that these activities occurred. Additionally, environmental data such as temperature, lunar phase, rainfall, and moon brightness were recorded, helping scientists understand how local conditions affect the frogs’ daily and seasonal habits.

The findings revealed that Kloof Frogs prefer cooler temperatures, with their breeding sites being significantly colder, up to 13°C lower in the morning and 10°C cooler in the afternoon, than surrounding areas. This is important as deforestation of their riparian habitat would lead to significantly higher temperatures along rivers, which would affect their behaviour and survival.

Deforestation is a threat to many other species and to ecosystem functioning, and disrupts water supplies. The breeding season lasts from September to April, but scientists noted a decline in egg-laying when the moon was at its brightest, possibly due to increased visibility to predators. This is another important finding, as any artificial light, which could mimic the moon, would reduce breeding behaviour and success in these frogs. Artificial urban light has also been shown to be a threat to many other species, including migratory birds and sea turtles.

Additionally, researchers observed female frogs returning to their egg clumps regularly to hydrate them using water stored in their bladder—a fascinating maternal behaviour. The study also captured the first recorded instance of crab predation on Kloof Frog eggs, highlighting an overlooked threat to their reproductive success.

This research demonstrates that camera traps can be an effective tool for studying amphibians, expanding conservationists’ ability to monitor species without human interference. By deepening the understanding of Kloof Frog behaviour, the findings will help predict how climate change and habitat degradation may impact the species. Ultimately, this information will aid in developing targeted conservation strategies to protect both the Kloof Frog and other threatened amphibian species.