Turning around the threat of extinction, one species at a time

Turning around the threat of extinction, one species at a time

By Yolan Friedmann – CEO, Endangered Wildlife Trust

Since our founding in 1973, the Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT) has established itself as a leader in wildlife conservation, focusing on the African species under greatest risk of extinction. Over the decades, so-called “species conservation” became frowned upon, with a view that only ecosystem and large habitat conservation is worth the funding, focus and energy. This view is not incorrect, and the EWT has spent considerable recourse successfully conserving large tracts of grasslands, mountains, wetlands, riparian systems and drylands.

The value of this work cannot be understated, as space, intact biodiversity and ecosystem function forms the basis of all life on earth. However, there is no doubt that a strong focus on saving species, with research, monitoring and specific activities focussing on the needs to individual species or their families is just as important if we are to stem the tide of extinction that threatens to overtake numerous species whose future survival requires more than just saving their habitat.

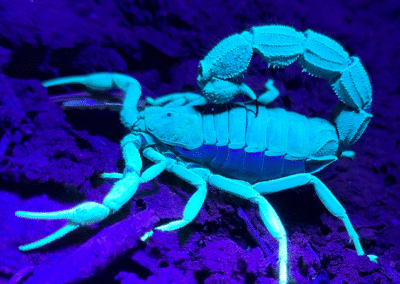

The threats facing the survival of individual species have amplified in recent years and include targeted removal from the wild for illegal trade (dead, alive or in parts), poisoning (direct or indirect), snaring, infrastructural impacts, alien invasive species, unsustainable use, and today, more than 48,600 species face the risk of extinction at varying levels. In response, the EWT has broadened our focus and our expert teams of specialists to ensure that we cover lesser-known, but equally important and often more at-risk species that include insects, reptiles, amphibians, trees and succulent plants. This makes the EWT the most diverse and extensive biodiversity conservation organisation in the region. And, if too little is known about the species in a particular area or what may be at risk, we have a specialist team that undertakes rapid biodiversity assessment, or bioblitzes, to quickly reveal the natural secrets that may be hiding in understudied areas, but may be facing a great risk of being lost to this generation or the next.

The IUCN’s Species Survival Commission issued the Abu Dhabi Declaration in 2024, emphasising the critical importance of saving species to save all life, calling on “… diverse sectors – including governments, businesses, Indigenous peoples and local communities, religious groups, and individuals – to prioritise species conservation within their actions, strategies, and giving, recognising that protecting animals, fungi, and plants is fundamental to sustaining life on earth.”

In October 2025, as nearly 10,000 members of the world’s conservation community gathered again in Abu Dhabi for the 5th IUCN World Conservation Congress, the message was clear: Save Species, Save Life. The congress featured very powerful calls for more urgent work to be done to stem the illegal wildlife trade, halt unsustainable use and prioritise funding, research and action in order to prevent mass extinction rates. Of the 148 motions that were adopted by the IUCN Members’ Assembly, a large number focussed on the need for intensified action and policy to address the issues facing species such as:

- Holistically conserving forests, grasslands, freshwater ecosystems and coral reefs and other marine ecosystems

- Species recovery for threatened taxa

- Sustainable use and exploitation of wild species

- Invasive alien species prevention

- Combatting crimes like wildlife trafficking and illegal fisheries

- One Health

Species can only survive and thrive within larger, functioning and healthy ecosystems, and more space is desperately needed for our ailing planet to retain its viability as a healthy host for all life. But the life that exists in micro-habitats, and those that face ongoing persecution which threatens to decimate all chances of survival, needs rapid and targeted interventions now.

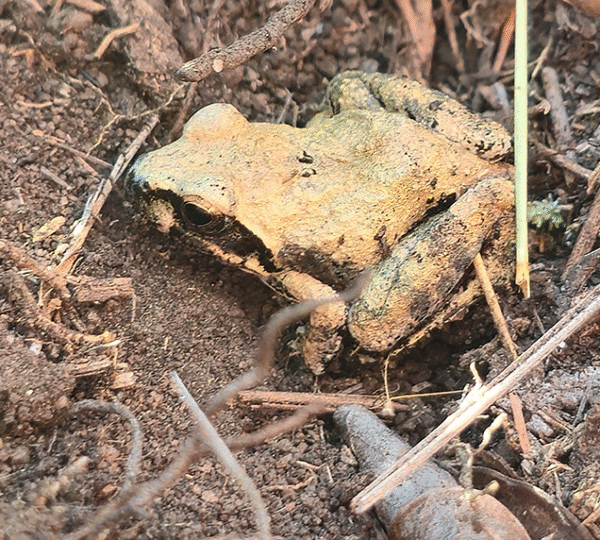

The EWT remains at the forefront of this work, having rediscovered populations of species thought to have gone extinct such as the De Winton’s Golden Mole, the Pennington’s Blue Butterfly, the Orange-tailed Sandveld Lizard, Branch’s Rain Frog and the Blyde Rondawel Flat Gecko, and effectively turning around the fate of others, such as the Cheetah, Wattled Cranes and the Pickersgill’s Reed Frog – once facing imminent risk of extinction, but now heading back to survival and expansion. Our work to discover, save, monitor and protect the most threatened, whether visible or not and whether charismatic or not, is unwavering. Together, we can turn the tide on extinction, on species at a time.

A cancelled event, storms, bad roads, no communication and vultures

A cancelled event, storms, bad roads, no communication and vultures

By Danielle du Toit, Birds of Prey unit – Field Officer

EWT pack members never let what could be a lost opportunity go to waste.

On a recent trip to the Pondoland region of the Eastern Cape, Senior Conservation Manager Lourens Leeuwner, and I almost swore never to embark on such a journey again.

I say almost—because you never know what the universe might throw at you.

We only discovered on arrival in Mbotyi that the Eastern Cape Avitourism Roadshow had been cancelled at the last minute due to severe storms. The conditions were grim: heavy winds had lifted roofs off houses, power lines were down, and cellphone towers were out of service. To top it off, the accommodation we had managed to find was leaking, mouldy, and filled with stray dogs that insisted on following me everywhere (what’s new?).

Nevertheless, we persevered. We spent time in the surrounding forest searching for Cape Parrots, Hornbills, and other elusive species. Exploring the village—something that took all of 20 minutes—we watched the community rally to clear roads using broken chainsaws, a clapped-out 1988 Toyota Hilux, and a frayed tow rope. One young man worked barefoot with heavy machinery on a slippery tar road in cold conditions—a snapshot of the resilience (and recklessness) of local life.

With no way to book alternative accommodation online, we stumbled across a cottage during our exploration and begged the owner to take us in. Fortunately, her guests were leaving, and we found room at the proverbial inn. From there, we resumed our quest for cellphone signal. After hours of holding our phones in the air and running in circles on a cleared road, the universe humbled us yet again—no signal.

But then, luck turned. Our new home, Destiny Cottage, had satellite internet. The signal barely reached inside, but it was enough. A view of the ocean from the lounge and a supper of Salti-Crax and cream cheese (after Lourens’s half-hour mission in the Lusikisiki Spar) lifted our spirits. Using the connection, we reached stakeholders and began to reschedule the cancelled roadshow meetings.

The following day took us to the Msikaba Vulture Colony. After a long drive, a missed turn, and a detour to a random campsite, we finally arrived. Hours drifted by as we watched Cape Vultures float effortlessly between cliff faces, rising on the thermals. Over coffee and Lourens’s famous peanut-butter-and-berry-jam sandwiches, we felt the frustrations of the previous days slip away.

On our final day, before heading back to Graaff-Reinet, we met with officials from the Eastern Cape Parks and Tourism Agency in Mthatha to discuss a future Wild Coast recce.

What began as a cancelled event in the middle of storms and silence ended with vultures, resilience, and new opportunities—reminding us why we do this work, and why it’s always worth carrying on, no matter the obstacles.

Left: state of the road. Centre: Searching for signal. Right: EWT in the snow

BioBlitz Mozambique National Parks: Baseline Biodiversity Data

BioBlitz Mozambique National Parks: Baseline Biodiversity Data

By Dr Darren Pietersen, EWT Biodiversity Survey Project Manager

When you think of Mozambique, most people immediately think of the beautiful coastal resorts, the exotic foods, and the crystal-clear waters along the coastline.

However, Mozambique has another facet which much fewer people explore—the expansive hinterland. Boasting three inland national parks south of the Save River (and several more north of this river), southern Mozambique really does offer something for every traveller.

As with much of Mozambique, biodiversity data, which is detail on what species occur where, is largely lacking for these three inland national parks—Limpopo, Banhine and the Zinave National Parks. These parks are co-managed by the Peace Parks Foundation (PPF) in partnership Administração Nacional das Áreas de Conservação (ANAC – Mozambique’s National Administration for Conservation Areas).

While the occurrence and numbers of large mammals are well known, and to some extent information about bird distributions, data about the dispersal of reptiles, amphibians, fishes and insects are much less clear.

The Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT) in collaboration with the PPF recently got an opportunity to start filling these knowledge gaps by undertaking BioBlitzes in and around these national parks. This BioBlitz falls under the Global Affairs Canada funded Restoring African Rangelands Project, implemented by Conservation International and its local affiliate, Conservation South Africa. These surveys are also being undertaken in collaboration with ANAC and the Maputo Natural History Museum.

So what is a BioBlitz? In short, a BioBlitz is a rapid biodiversity survey undertaken by a team of scientists and/or members of the public, and often involve an educational or outreach component.

BioBlitzes aim to document as much of the biodiversity (species) present in a particular area within a relatively short space of time. They are not meant to provide an exhaustive list of species occurring in an area as that would take years of continuous surveys to achieve. Rather, they provide a snapshot of the biodiversity that is present, and provide baseline data. It is generally assumed that most of the common species will be detected during a BioBlitz, and with a bit of luck at least some of the rarer and/or inconspicuous species will also be recorded.

The EWT,-PPF,-ANAC BioBlitzes are multi-taxon biodiversity surveys, meaning that we aim to document as many species at each site across nearly all of the major taxonomic groups; birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, plants, fishes and insects. To this end we are using both in-house expertise and external consultants to ensure that we can accurately document as much of the biodiversity that we find as possible.

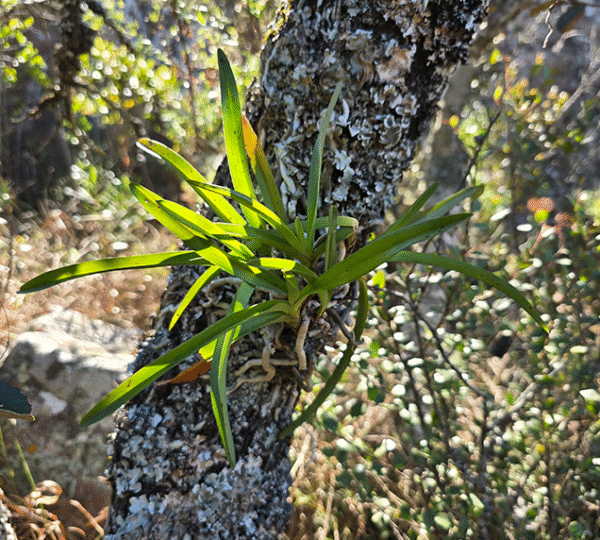

During August 2025, two EWT team members undertook an initial 12-day trip through all three national parks to plan the BioBlitzes planned for September and December 2025. During this trip the team documented 1,485 occurrences of 419 species. Birds dominated the records (994 records of 211 species), although data were recorded for all the main taxonomic groups, including fungi. The team also documented the first occurrence of the Brandberg Euphorbia (Euphorbia monteiroi) in Mozambique. Also found was a population of Striped Green Spurge (Euphorbia knuthii) which indicates a range extension and partially fills the gap between the two currently known and presumed isolated populations, suggesting that this apparent isolation may be the result of incomplete survey effort rather than true isolation. Of the roughly 200 invertebrate species recorded, two are potentially undescribed: a scuttle fly (Phoridae: Aenigmatistes sp.) and a longhorn beetle in the subfamily Cerambycinae. Other highlights included seeing a raft of more than 300 Great White Pelicans (Pelecanus onocrotalus) and a juvenile Greater Flamingo (Phoenicopterus roseus) in Banhine National Park, and another juvenile Greater Flamingo in Zinave National Park. The team also managed to capture a Mashona Mole-rat (Fukomys darlingi) in Zinave National Park, a species that is not often seen.

The EWT and PPF are planning four BioBlitz expeditions targeting nine sites across the three national parks until December and, if the initial results are anything to go by, there are likely to be several interesting discoveries in store for the team during these upcoming probes.

Soil Sampling in Banhine National Park

Old Salt Trail Soutpansberg: Experience Nature and Biodiversity

Old Salt Trail Soutpansberg: Experience Nature and Biodiversity

By Eleanor Momberg

Amazing. Mind-boggling. Beautiful.

These are among the words used by Jo Bert, the Endangered Wildlife Trust’s Senior Graphic Designer, following their five-day hike of the Old Salt Trail in the Soutpansberg.

Jo had joined a group of hikers to experience the Trail that spans the upper reaches of the Soutpansberg Mountains in Limpopo.

“I did not have context of the trail. I had been telling the story for months and all I had to go on was the information that had been supplied and the photos I had seen. A lot of the story so far has been conservation-focused, so going on the trail enables us to tell the story better from a marketing perspective and, through that, get more people to join,” said Jo.

For someone who is largely deskbound at the EWTs Conservation Campus in Midrand, this was an ideal opportunity to get back to nature and to collect photos and video material needed for future projects.

“It was amazing. I honestly love getting out away from my desk. It was so beautiful. I think the best part is that I have looked at those photos so many times, and to actually be in that space, to stand where the photo was shot, puts the whole thing into a different perspective,” they say.

The intrepid team of four hikers were led by the EWT Medike Reserve Rangers Tharollo Mthisi and Khathutshelo Mukhumeni. The Old Salt Trail is a 73km, five-day, four-night slackpacking adventure traversing numerous private properties in an area that now largely comprises the Western Soutpansberg Nature Reserve.

The hike starts at the Medike nature reserve, which is owned and managed by the EWT. On Day One, you climb 11.5km to Leshiba Luvhondo Camp. On the second day, the hikers embark on a 15.5km hike to Sigurwana Lodge, followed on the third day with a trek of about 15km to Lajuma Wilderness Camp. On the fourth day, the hike takes about 19km you back to Leshiba Venda Village Lodge from where you return via an 11km route to Medike on Day Five where the adventure ends.

Before the hikers set off from the bottom of the Sand River Gorge, Tharollo and Khathutshelo give a safety briefing and all luggage is loaded into a vehicle to be taken to the overnight accommodation at Leshiba. All hikers carry with them are a day pack.

“You carry a day pack with you with your lunch in, maybe a spare jersey and your water,” said Jo. “The first day I packed way too much, because I didn’t realise that we had so much food given to us, so I brought a whole bunch of snacks with me, and a whole lot of clothes because I didn’t know how wet we were going to get or if it was going to be super hot. I also had a bird book, but then realised that Therollo and Khathu have all the apps on their phones so we just identified with that. So every single night I was taking things out of my bag and by the last day I only had my lunch and my water and a very light jersey”.

On the first two days of the Old Salt Trail hikers not only have to tend with steep and rocky slopes, but also cross bushveld, forests, grassland and savannah beside enjoying a variety of San and Khoekhoe rock art and ancient artefacts.

“The cultural heritage in that area is so amazing. And there are so many spots where you are in the ruins of an old village where there are bits of clay or you can see the foundations of a house. And the places with the rock paintings are fascinating,” Jo explained.

For paintings that have been damaged by years of weathering, a phone APP was used to highlight the original paintings. “A lot of people thought that the paintings were about daily activities, but they are about special occurrences and a lot of the paintings in that area are about spirits, ancestors and trances; a lot of really spiritual stuff and not just day to day things. And there’s a lot of giants in there that you can’t really see with the naked eye, but when put through the APP you can see them and it is amazing,” said Jo.

On Day Three hikers head straight towards a rocky cliff and a waterfall into a Fever Tree forest before climbing to the top of Mt Lajuma, the highest point of the Soutpansberg at more than 1,727m above sea level.

“It is crazy. When I got to the top of the mountain, I looked around to see everything below and realised I had forgotten that I was actually on top of the Soutpansberg. I actually only remembered we were up on the mountain when I looked out from on top of Mt Lajuma and I saw how far down everything else was,” said Jo.

For this adventure, hikers need to be reasonably fit.

“On Day Four there is a section where you have to climb up The Chimney as they call it. I do rock climbing and I am ashamed to admit that I needed a hand in some places. It’s not the most insane climbing, but it is fairly technical,” said Jo. “I think you have to be fairly fit, but I still managed even though I was a bit ill, so it’s not an impossible thing.

Hikers have to be prepared to walk long distances. Although there is a break for lunch and several short stops in between, it is an all-day walk across sometimes flat areas, traversing unsteady and rocky terrain, rivers and other obstacles, and scrambling up some challenging cliffs.

“You do have to be fairly confident in your ability. If you are reasonably fit, you can do it,” they said.

The main calling card for the Soutpansberg and the Old Salt Trail is the variety of ecosystems. Jo points out that the terrain constantly changes.

“You start on Medike where it is fairly dry … and by the time you get to Leshiba it is marshy on the side of the mountain, and on the fourth day you’re in a Yellowwood forest. Even on the first day you start to get up into the mist belt and by Day Two you’re seeing Old Man’s Beard lichen everywhere. Some days you’re walking through grasslands or marsh and then you’re in Bracken taller than you. It changes within seconds”.

Jo added: “The amount of birds we saw was amazing. We saw and heard birds I had never seen or heard in my life. There are so many mushrooms and there are tiny little frogs and flowers and we saw so many beautiful beetles… So many amazing things that I have never seen before, and I have seen a fair amount, but this was just blowing my mind – the amount of nature and biodiversity that I have never even seen before and it is such a small area”.

The Soutpansberg is a unique refuge. “If you go to the Kruger National Park, you can drive for hours in the same kind of veld. Go to Soutpansberg and walk around for two hours and you have seen six different biomes, you’ve climbed a mountain, you have walked across marshy flats and it is a complete variety every five minutes. We saw zebra and quite a couple bushbuck, klispringers, and we found several snake skins,” they said.

Jo said they did not even take much note of the iconic waterfall because there were so many butterflies and River Fever Trees.

“I was just looking at the trees and the mosses and large butterflies and the one lady that was with us knew all the species of butterfly. I learnt quite a lot.”

Accommodation

Jo has nothing but praise for the accommodation at Leshiba Luvhondo Camp and Venda Village and Sigurwana Lodge describing them as beautiful and luxurious. Although the Lajuma Wilderness Camp was more rustic, it was comfortable, they said.

After a day of hiking, the warm facecloth at Leshiba handed to hikers and drinks and snacks served are a blessing. Moreso the food, the comfortable huts, rondawels and tented camps with their welcoming beds—with hot water bottles—and bathrooms at the end of a day-long slog through the bush.

Jo recommends booking accommodation at Medike for the night before the start of the hike, and the last night – if you are not from nearby. This is because of the time it takes to travel there. The hike starts in the morning and ends in the afternoon.

“We stayed at the Stone Cottage at Medike, which was really nice. If someone is coming from Joburg it is worth staying over because it is a long hike”.

Two weeks after completing the hike Jo said they were still trying to process everything seen and experienced.

“It was difficult to process in the moment and the more I think about it, I still can’t appreciate the amount we actually saw. It was mind boggling,” they said.

EWT USA: Supporting African Conservation and Tax-Deductible Giving

EWT USA: Supporting African Conservation and Tax-Deductible Giving

Founded in 1973, the Endangered Wildlife Trust has championed the fight for survival of dozens of African wildlife species for more than five decades. Through its strategic pillars of saving species, conserving habitats and benefitting people, the EWT is charting a bold new path to 2050 through the implementation of a Future Fit Strategy to secure wildlife, ecosystems and work with the local communities within them.

Alongside the development of the Strategy has been the registration of the EWT USA as a 501(c)(3) non-profit conservation organisation in the United Statement with a focus on supporting conservation and community development in East and southern Africa.

The EWT USA was registered on 4 December 2024.

As a Section 501(c)(3) organisation registered in terms of the United States Internal Revenue Code, the EWT USA is tax exempt. This means that donors are able to deduct any contributions made to the EWT USA under IRS Section 170. This is an incentive to individuals and business because all contributions are tax deductable. This makes it the most tangible way to support the EWT USA.

The EWT USA is led by:

- Mr Ewan Macaulay – President

- Ms Yolan Friedmann – Vice President

- Mr Dirk Ackerman — Director

- Mr David McCullough – Secretary and Treasurer

In South Africa, the EWT is registered as a Trust in accordance with the Trust Property Control Act No. 57 of 1988, with registration number IT 6247 under the Master of the High Court.

As a Section 18A Tax Exemption Institution in South Africa, individual or corporate donors are able to claim a tax deduction for their contributions to the EWT. In order to do this, the EWT will issue a Section 18A tax deductible receipt to a donor. By receiving a tax deductible receipt donors are potentially able to reduce their taxable income. This incentivises charitable giving and encourages greater support for a conservation body such as the EWT.