Sparking to save small vertebrates

By Darren Pietersen, EWT Medike Reserve Manager & Ecologist.

Fences are ubiquitous structures, especially in South Africa, but increasingly across Africa. They are used to keep wildlife in (or out, depending on the farmer) of a property. They demarcate land parcels, help to keep livestock and wildlife off of roads, prevent the spread of diseases, and are used for security.

There are also many types of fences – non-electrified fences, game fences, cattle fences, Bonnox fences and, of course, electrified fences.

Electrified fences are mainly used around protected areas to keep wildlife in, thereby minimising human-wildlife conflict. They are also found around game farms to contain animals and keep intruders out. If constructed correctly, fences work really well for their intended purpose. But, there is also a dark side to electrified fences – they are silent killers.

While working for the Endangered Wildlife Trust during his studies Wits University in the mid-2000’s, Andrew Beck examined the impact of electrified fences on wildlife across South Africa. Andrew estimated that in the region of a whopping 30,000 reptiles, predominantly tortoises, are killed on electrified fences in South Africa annually. An earlier study, and several subsequent studies, have similarly highlighted the high toll taken on tortoises by electrified fences, although not quantifying the overall threat.

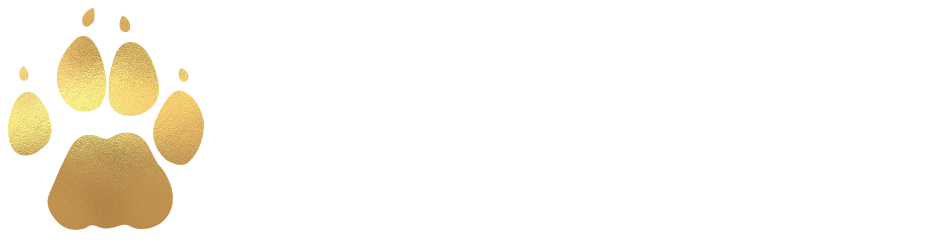

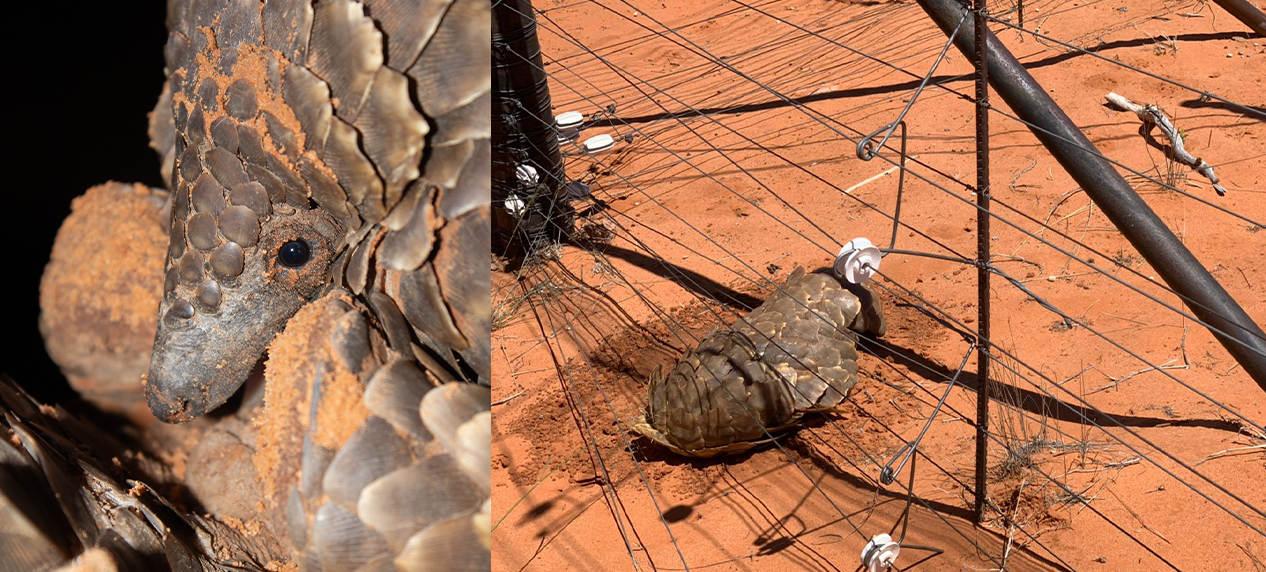

And it is not just tortoises that are bearing the brunt. It has been long known that pangolins are also affected by electrified fences, but it was not until 2016 that colleagues and I quantified this threat.

Based on available evidence, we estimated that in the region of 1,000 Temminck’s Pangolins are killed by electrified game fences in South Africa annually. And that’s just part of the story, given that there are an increasing number of livestock farmers fitting electrified strands to their fences in attempts to exclude Black-backed Jackal and Caracal from their farms. If we include the mortalities on these livestock fences as well, then around 2,000 Temminck’s Pangolins are killed by electrified fences in South Africa alone every year. That is 20–40 times more Temminck’s Pangolins killed on electrified fences than by trade in South Africa annually.

This is a serious conservation concern, because electrified fences have already resulted in the local population decreases and extinctions of tortoises (and perhaps pangolins) in some regions.

Yet the solution can be bizarrely simple – and cheap. Extensive fieldwork has indicated that by raising the lowest electrified strand to 300 mm above the ground (rather than the 250 mm or lower demanded by most provincial legislation), mortalities of all species can be reduced by up to 95%. Some large, well-established Big-5 reserves such as the Associated Private Nature Reserves raised their lowest electrified strands more than 10 years ago. And not a single pangolin or tortoise mortality has been recorded along these raised sections since. Just as importantly, they recorded no increase in predators or other animals leaving the reserve.

Most provinces have legislation governing the construction of electrified fences, and discussions need to be had with the relevant authorities to get this legislation amended where necessary. A further contributing factor is that the insurance industry apparently also has their own specifications for electrified fences, and if a fence does not meet their standards then a claim for any losses incurred will be denied.

Because one solution will rarely work in all situations, we have also undertaken extensive field trials with partners including Stafix, JVA, Pangolin.Africa, WESSA and The Kalahari Wildlife Project to design smart energisers that can prevent or reduce electrified fence mortalities. We produced two prototypes – a larger unit aimed at the wildlife industry and a smaller unit aimed at livestock farmers. In short, these energisers monitor the current on the electrified wires and have the ability to automatically switch off the current to specified wires for a pre-determined period of time, affording any trapped animal time to extricate itself from the fence. Although the initial results were positive and some farms reported no fence mortalities while running these units, other farmers commented that the system was too complicated, with the result that it was not maintained or used properly. However, the EWT believes that this system does have merit, and hopefully in time a workable, cost-effective version can be designed.

Changing the fence configuration could have inadvertent negative consequences, however. This could include large carnivores (Cheetah and African Wild Dog in particular) leaving reserves, resulting in human-wildlife conflict. There is no point in solving one problem just to create another one, and finding an effective solution that works for all species will require input from the wildlife and livestock industries, species specialists, conservationists, fence manufacturers and fence installers.

Overall, though, the evidence of the threat posed by fences remains and effective solutions are known. Because of this we are working to engage with all relevant role players to try and arrive at a workable solution to protect not only our megafauna and carnivores, but also our smaller species.